Review: are the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 worth the money for CG?

Are the top-of-the-range GPUs from NVIDIA’s new GeForce RTX 50 Series worth the money? Jason Lewis put the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 through an exhaustive series of real-world tests in DCC applications to find out how much bang they offer CG artists for their bucks.

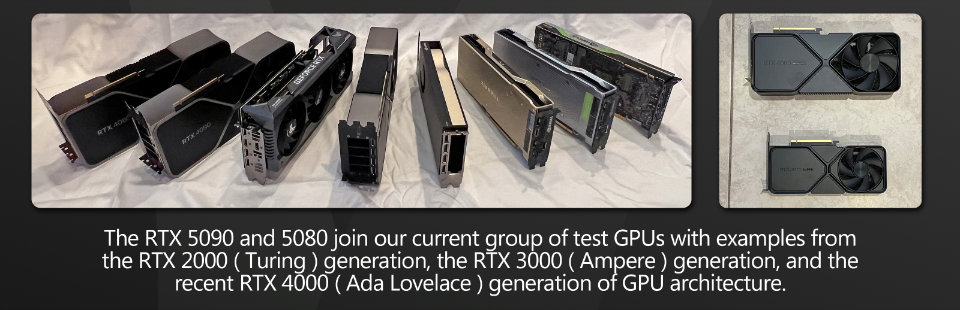

Welcome to CG Channel’s latest GPU group test. In this in-depth review, I will be taking a look at the two top-of-the-range cards from NVIDIA’s current range of Blackwell consumer GPUs, the GeForce RTX 50 Series, pitting the GeForce RTX 5090 and GeForce RTX 5080 against their previous-generation counterparts in a series of real-world tests in DCC applications.

If you’re a regular reader, you will have seen my early test results for the two cards, which I posted back in February. Normally, I like to get full reviews out closer to the release dates of new GPUs, but it has take much longer than usual for CG software developers to update their applications to take advantage of – and, in some cases, even run on – the new architecture.

To pick a few examples, it wasn’t until June that Redshift officially supported the new cards, and even when I was completing my tests several months later, Cinebench would not run on Blackwell GPUs at all, and SolidWorks would not display or report any viewport FPS data.

However, most of the DCC apps I test with now run reliably on the new GPUs, so I am confident in presenting my findings. So how well do the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 perform in CG work?

Jump to another part of this review

Specifications

Testing procedure

Benchmark results

Other considerations

Prices

Verdict

Technology focus: GPU architectures and APIs

Before I get to the review itself, here is a quick recap of some of the technical terms that you will encounter in it. If you’re already familiar with them, you may want to skip ahead.

Like NVIDIA’s previous-generation Ada Lovelace, Ampere and Turing GPUs, the current Blackwell GPU architecture features three types of processor cores: CUDA cores, designed for rasterization and general GPU computing; Tensor cores, designed for machine learning operations; and RT cores, intended to accelerate ray tracing.

In order to take advantage of the RT cores, software has to access them through a graphics API: in the case of the applications featured in this review, either DXR (DirectX Raytracing), used in Unreal Engine, or NVIDIA’s OptiX, used in most offline renderers.

In some renderers, the OptiX rendering backend is provided as an alternative to an older backend based on NVIDIA’s CUDA API. The CUDA backends work with a wider range of NVIDIA GPUs, but OptiX enables hardware-accelerated ray tracing, and usually improves performance.

Specifications

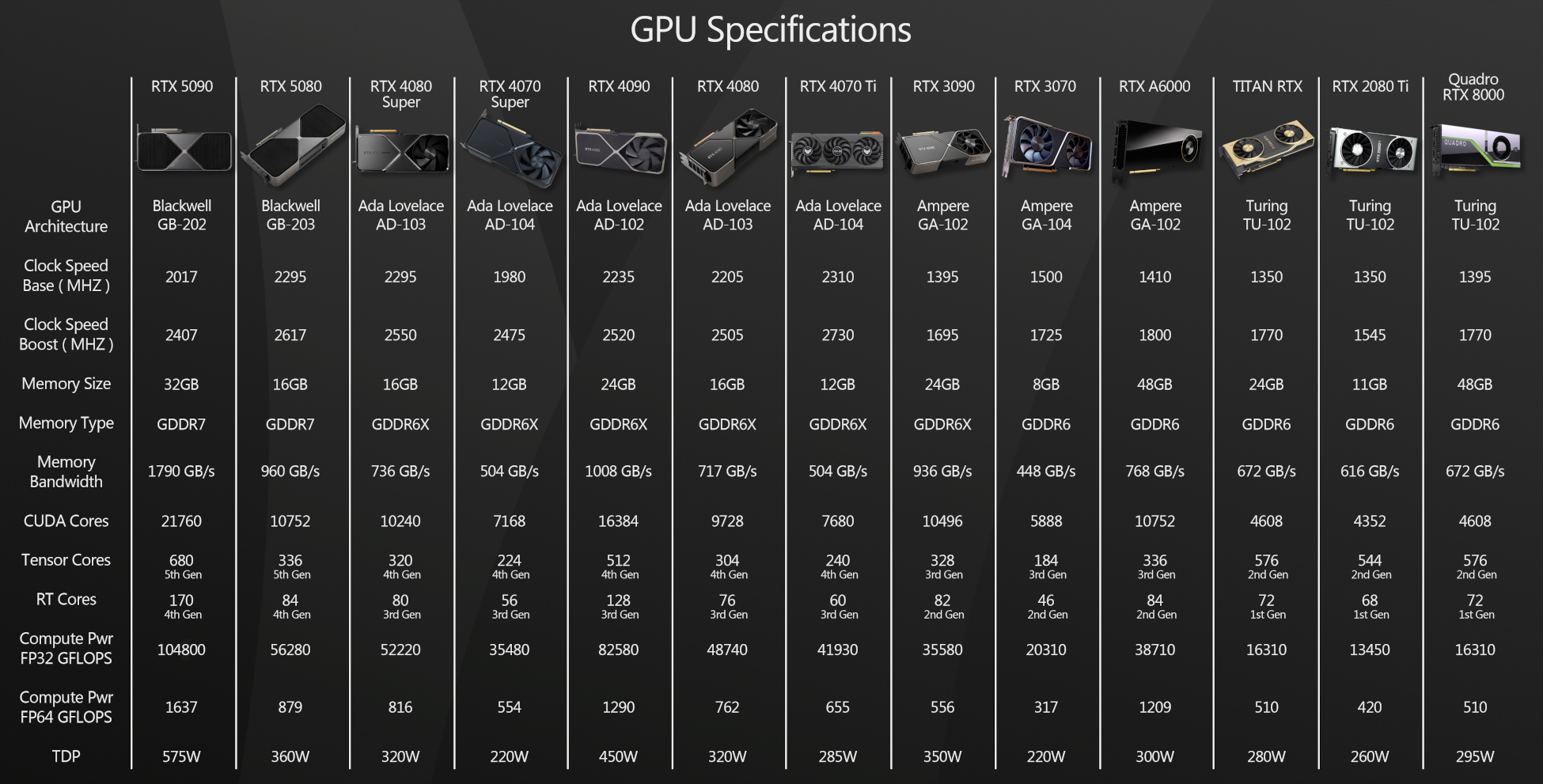

Next, let’s take a look at the technical specifications for the new GPUs. You can find deep dives into the Blackwell GPU architecture on mainstream tech news sites, so I’ll be focusing on the specs most relevant to the performance of CG software here.

First, let’s take a look at NVIDIA’s new flagship consumer-level GPU, the GeForce RTX 5090. The 5090 is meant as a direct replacement for the previous generation top-tier GPUs, the GeForce RTX 4090 and GeForce RTX 3090, and a successor to the earlier Titan RTX.

The 5090 uses a slightly cut-down GB202 processor, with 21,760 CUDA Cores, 680 fifth-generation Tensor Cores, and 170 fourth-generation RT cores, and runs at a base clock speed of 2.01 GHz, with a boost clock speed of 2.41 GHz.

The big change over the earlier flagship cards is the memory configuration. Not only do we get an architectural upgrade to GDDR7, with a 512-bit bus, but also a bump in memory capacity, from the 24 GB that has been standard for three previous generations, to 32 GB.

Combine the new processor with the new memory configuration, and you get a theoretical performance of 104.8 TFLOPS of single precision compute power, and 1.64 TFLOPS of double precision compute power, up from 82.6 TFLOPS and 1.29 TFLOPS for the GeForce RTX 4090.

The other big change is the form factor. While the GeForce RTX 3090 and 4090 were massive three-slot cards, the 5090, despite its more powerful GPU and larger memory layout, goes back to a standard dual-slot configuration. Its length and height remain the same, at 304 x 137 mm, but width falls from 61 mm to 40 mm. It isn’t quite as heavy as the earlier cards, but it feels weighty enough that I still use a rear brace to make sure that it doesn’t sag over time, potentially damaging the PCIe connector on the card, or the slot on the motherboard.

Like the cards from the previous two generations, the 5090 uses a 16-pin 12VHPWR connector; and it has a TDP of 575W. As a result, NVIDIA recommends at least a 1,000W PSU, but I like to allow a bit of breathing room, so my test system uses a 1,300W PSU.

The second new GPU on test is the GeForce RTX 5080, the next step down from the 5090. It is a direct successor to the previous generation GeForce RTX 4080 and 4080 Super, and to a lesser extent, the GeForce RTX 3080 and 3080 Ti.

It uses a GB203 GPU sporting 10,752 CUDA cores, 336 fifth-generation Tensor cores, and 84 fourth-generation RT cores, and runs at a base clock speed of 2.30 GHz, with a boost clock speed of 2.62 GHz.

The 5080 uses GDDR7 memory, an upgrade from the 4080 and the 4080 Super, but retains the 256-bit bus, and has the same 16 GB memory capacity. This makes for a theoretical compute performance of 56.3 TFLOPS for single precision, and 0.88 TFLOPS for double precision.

Unlike the triple-slot 4080 and the 4080 Super, the 5080 is a dual-slot card with the same dimensions as the GeForce RTX 5090 (304 x 137 x 40 mm).

It uses a 16-pin 12VHPWR connector, and has a TDP of 360W.

Click the image to view it full-size.

Testing procedure

I tested the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 against all of the GPUs from my previous group test, which includes many of the Ada Lovelace GeForce RTX 40 Series GPUs, several Ampere GeForce RTX 30 Series and Turing GeForce RTX 20 Series GPUs, plus a couple of older workstation cards. You can see the full lineup in the specs table above.

For the test machine, I am still using the dependable Xidax AMD Threadripper 3990X system that I reviewed in 2020. Although it is now five years old, it is still an extremely capable system and doesn’t appear to be a bottleneck for any of the GPUs tested.

The current version of the test system has the following specs:

CPU: AMD Threadripper 3990X

Motherboard: MSI Creator TRX40

RAM: 128 GB of 3,200 MHz G.Skill DDR4

Storage: 2TB Samsung 970 EVO Plus NVMe SD / 1 TB WD Black NVMe SSD / 4 TB HGST 7,200 rpm HD

PSU: 1300W Seasonic Platinum

OS: Windows 11 Pro for Workstations

The only GPU not tested on the Threadripper system was the GeForce RTX 3070. I no longer have access to a desktop RTX 3070, so testing was done using the mobile RTX 3070 in the Asus ProArt Studiobook 16 laptop from this recent review.

In that review, I determined that across a range of tests, the mobile RTX 3070 was around 10% slower than its desktop counterpart, so here, I added 10% to the scores to approximate the performance of a desktop card. It isn’t an ideal methodology, but it gets us to the right ballpark.

For testing, I used the following applications:

Viewport performance

3ds Max 2026, Blender 4.4, Chaos Vantage 2.1.1, D5 Render 2.10.2, Fusion, Maya 2026, Modo 17.1v1, Substance 3D Painter 11.0.2, Unigine Community 2.19.1.2, Unity 2022.1, Unreal Engine 4.27.2 and 5.5.4

Rendering

Arnold for Maya 5.5.2, Blender 4.4 (Cycles renderer), KeyShot 11.2.0, Maverick Studio 2025.1, Redshift for 3ds Max 2025.6.0, Solidworks Visualize 2025, V-Ray GPU 7 for 3ds Max

Other benchmarks

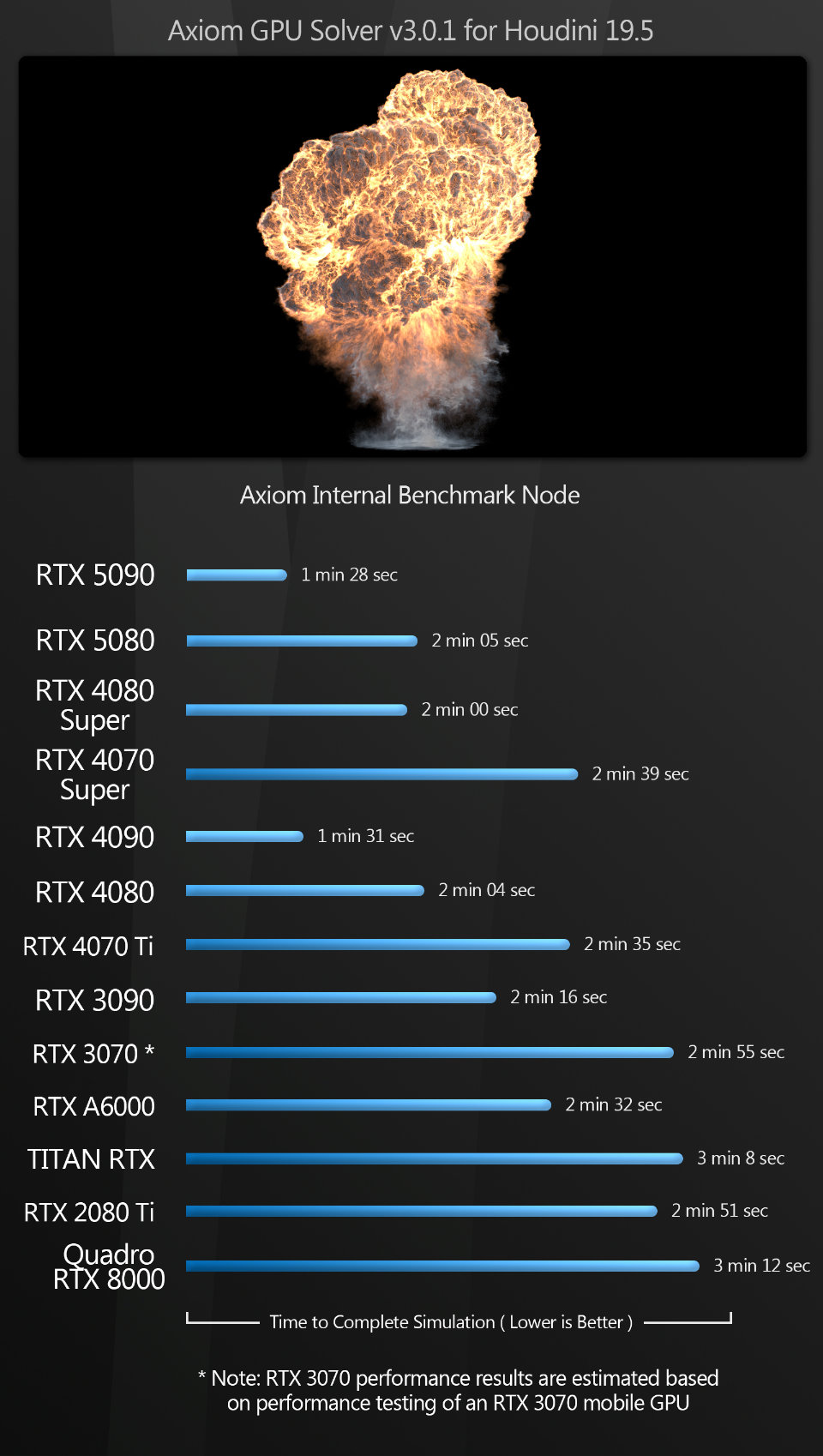

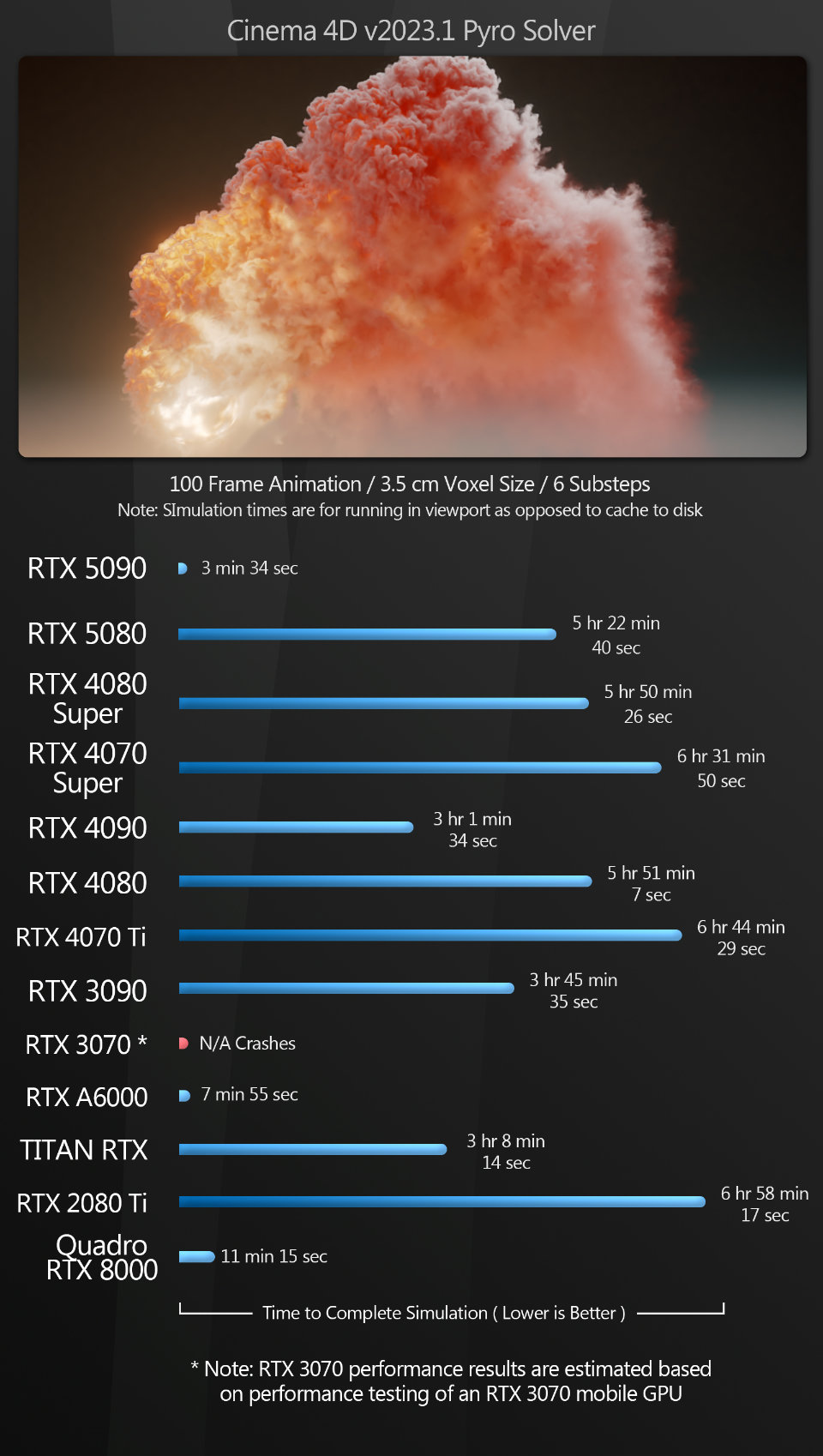

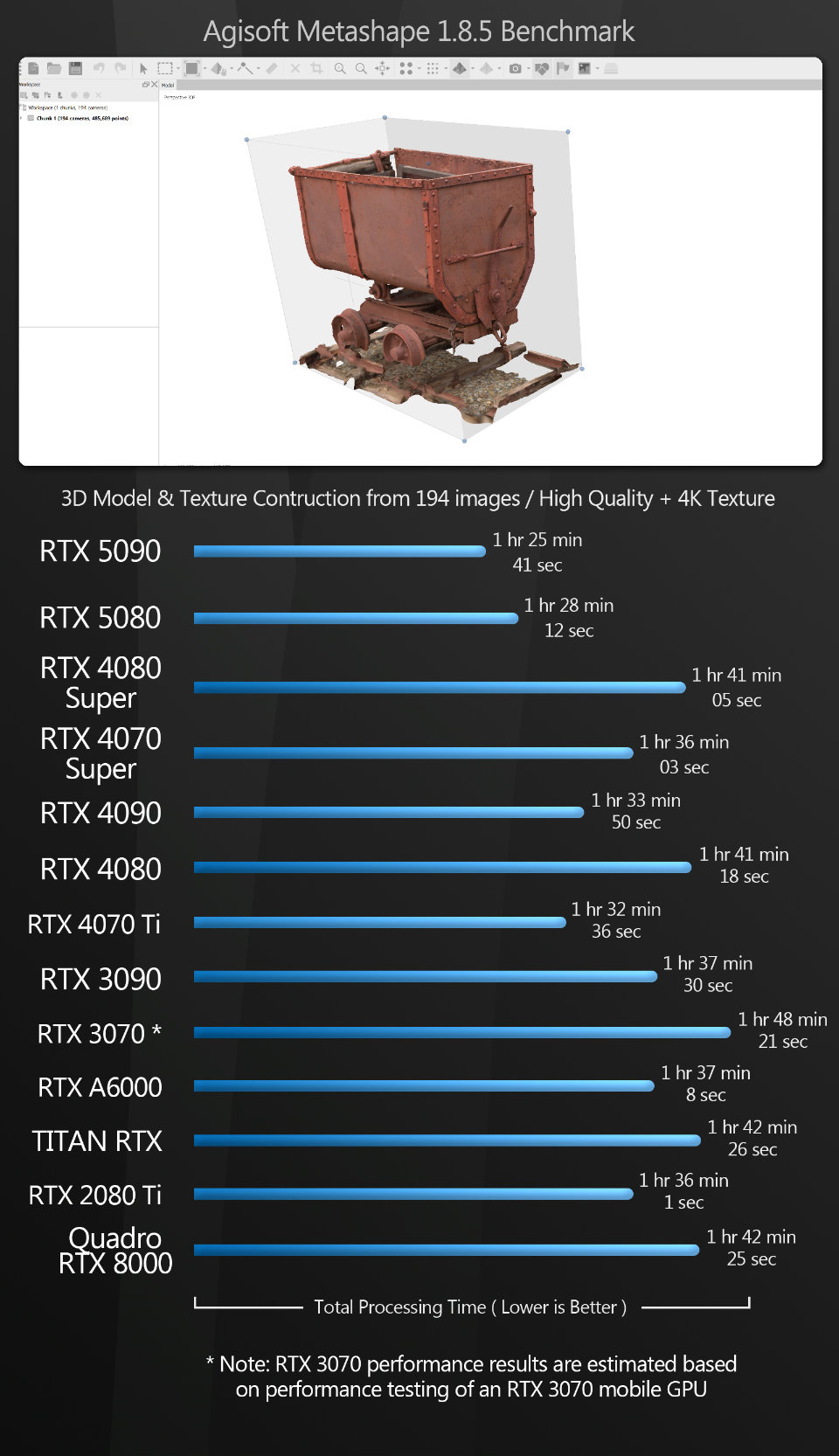

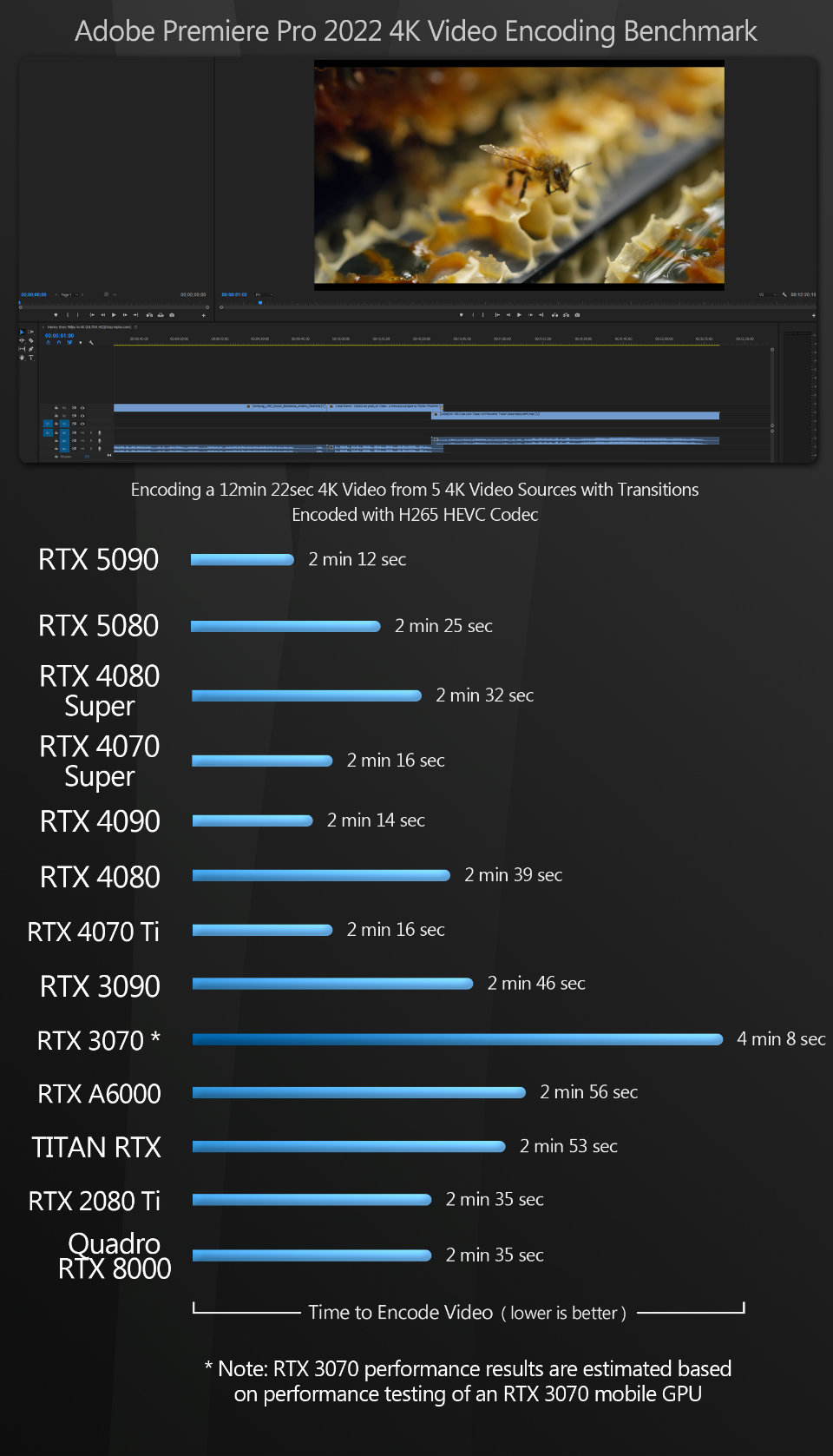

Axiom 3.0.1 for Houdini 19.5, Cinema 4D 2023.1 (Pyro solver), Metashape 1.8.5, Premiere Pro 2022

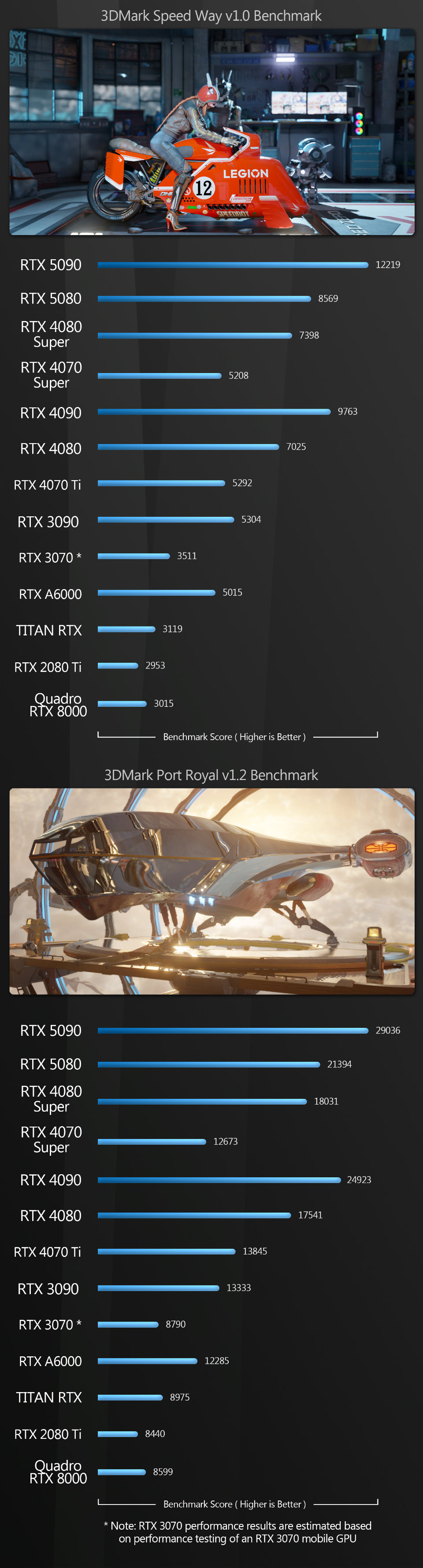

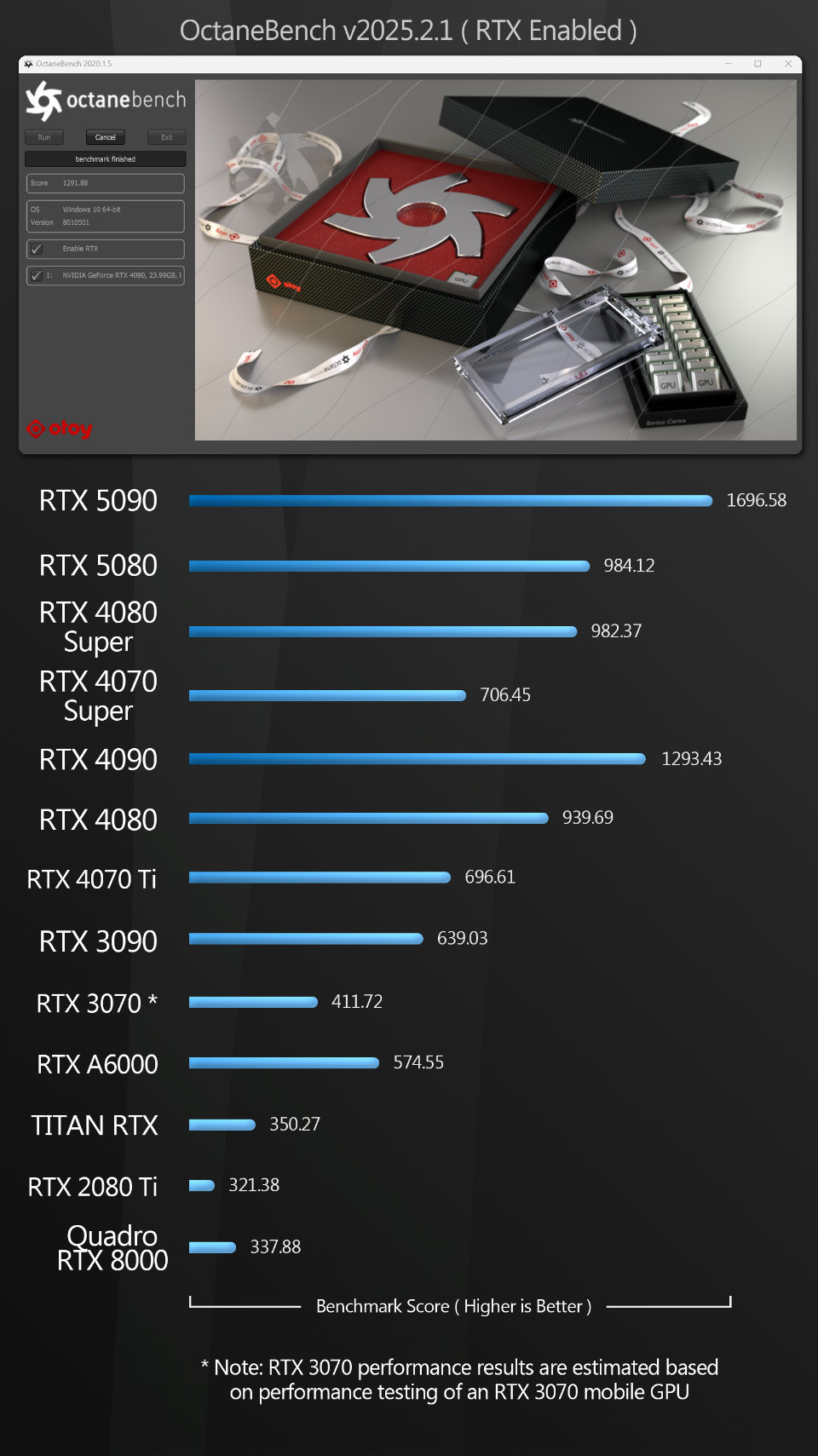

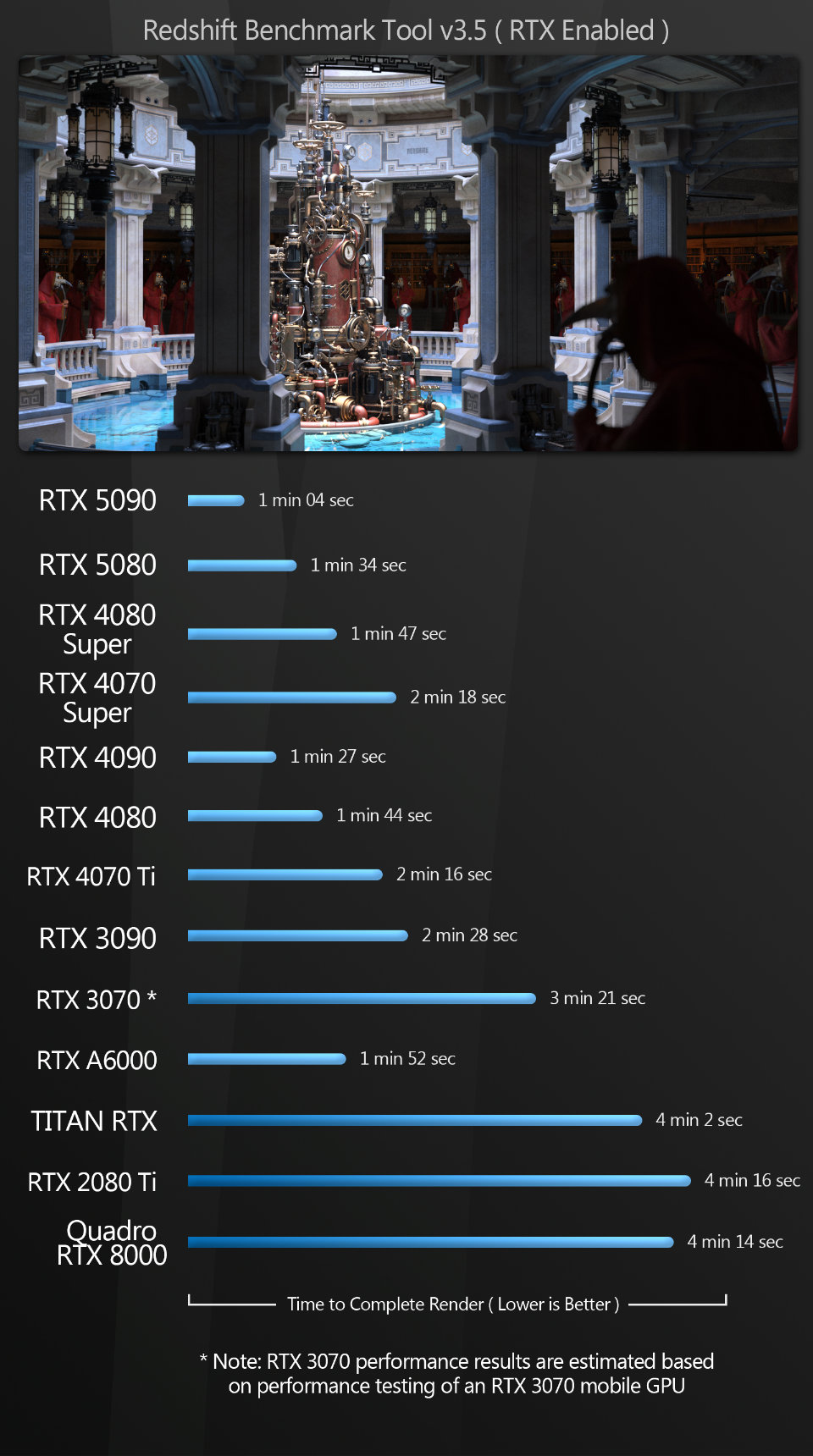

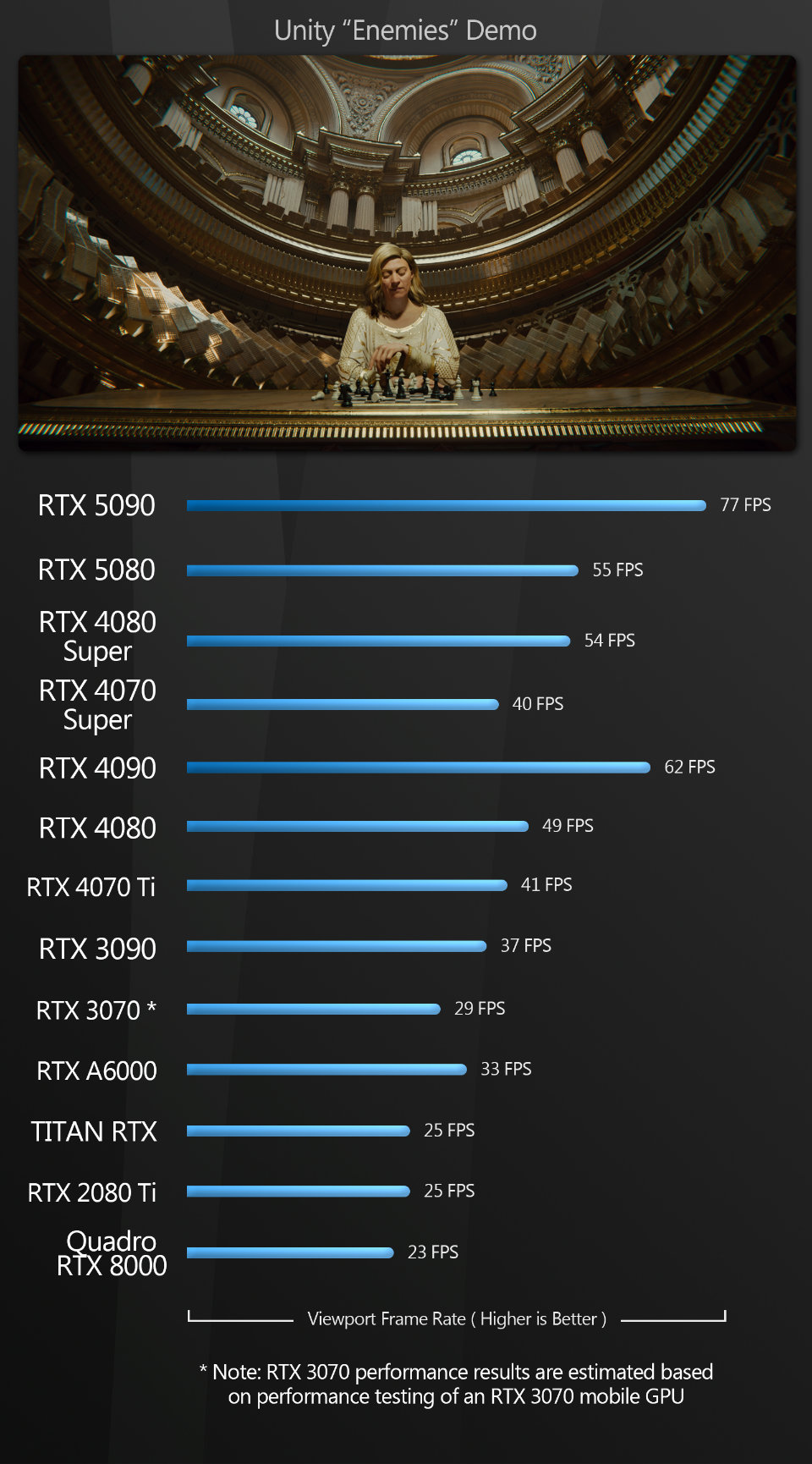

Synthetic benchmarks

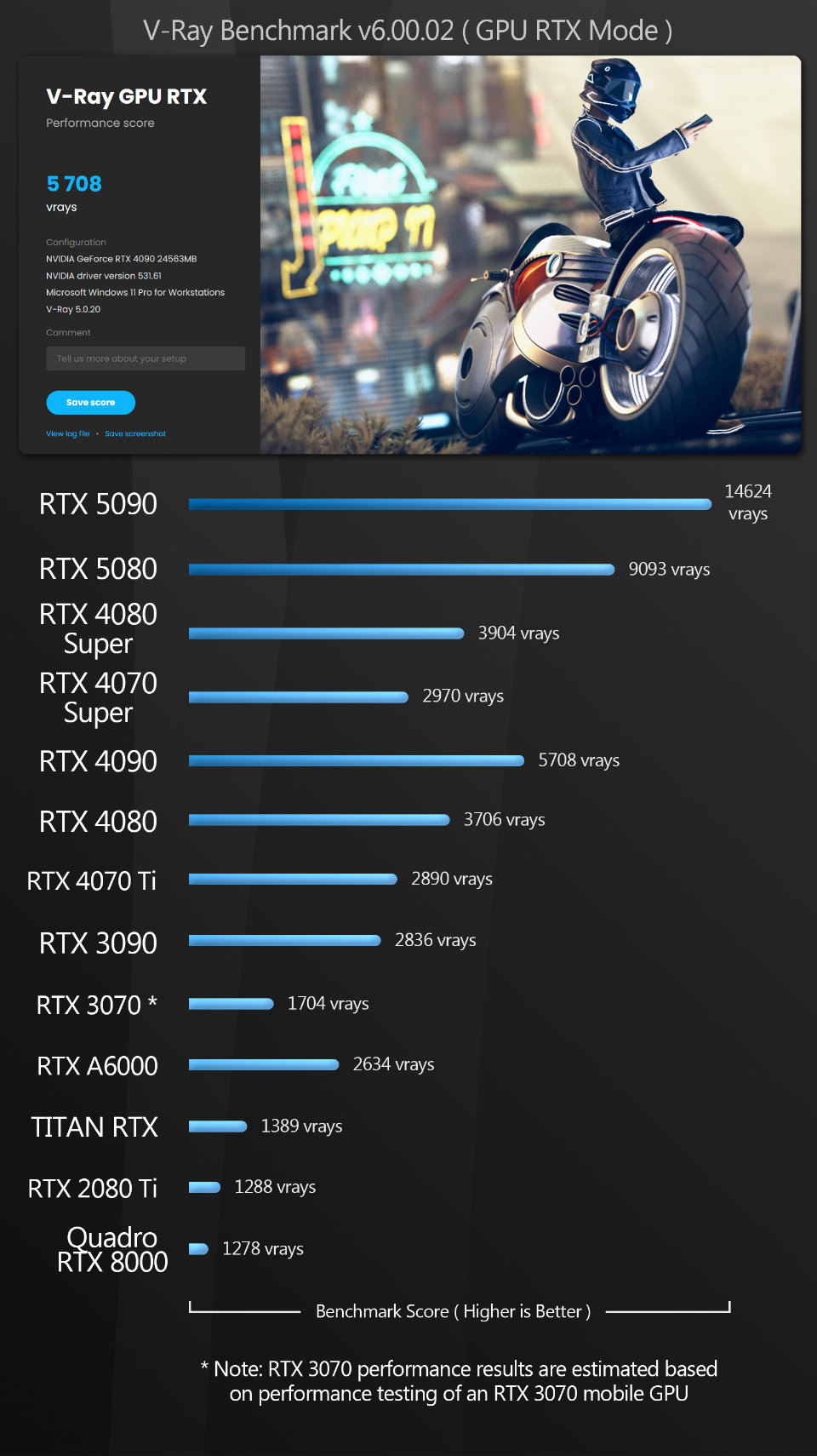

3DMark Speed Way 1.0 and Port Royal 1.2, OctaneBench 2025.2.1, Redshift Benchmark 3.5, Unity Enemies Demo, V-Ray Benchmark 6.00.02

All benchmarking was done with NVIDIA Studio Drivers installed for the GeForce RTX GPUs and workstation drivers installed for the RTX 6000 Ada, RTX A6000 and Quadro RTX 8000. You can find a more detailed discussion of the drivers used later in the article.

In the viewport benchmarks, the frame rate scores represent the figures attained when manipulating the 3D assets shown, averaged over five testing sessions to eliminate inconsistencies. In all of the rendering benchmarks, the CPU was disabled so only the GPU was used for computing. The test system drives a pair of 32” displays running at their native 3,840 x 2,160 resolution, but when testing viewport performance, the software viewport was constrained to the primary display: no spanning across multiple displays was permitted.

Benchmark results

Viewport performance

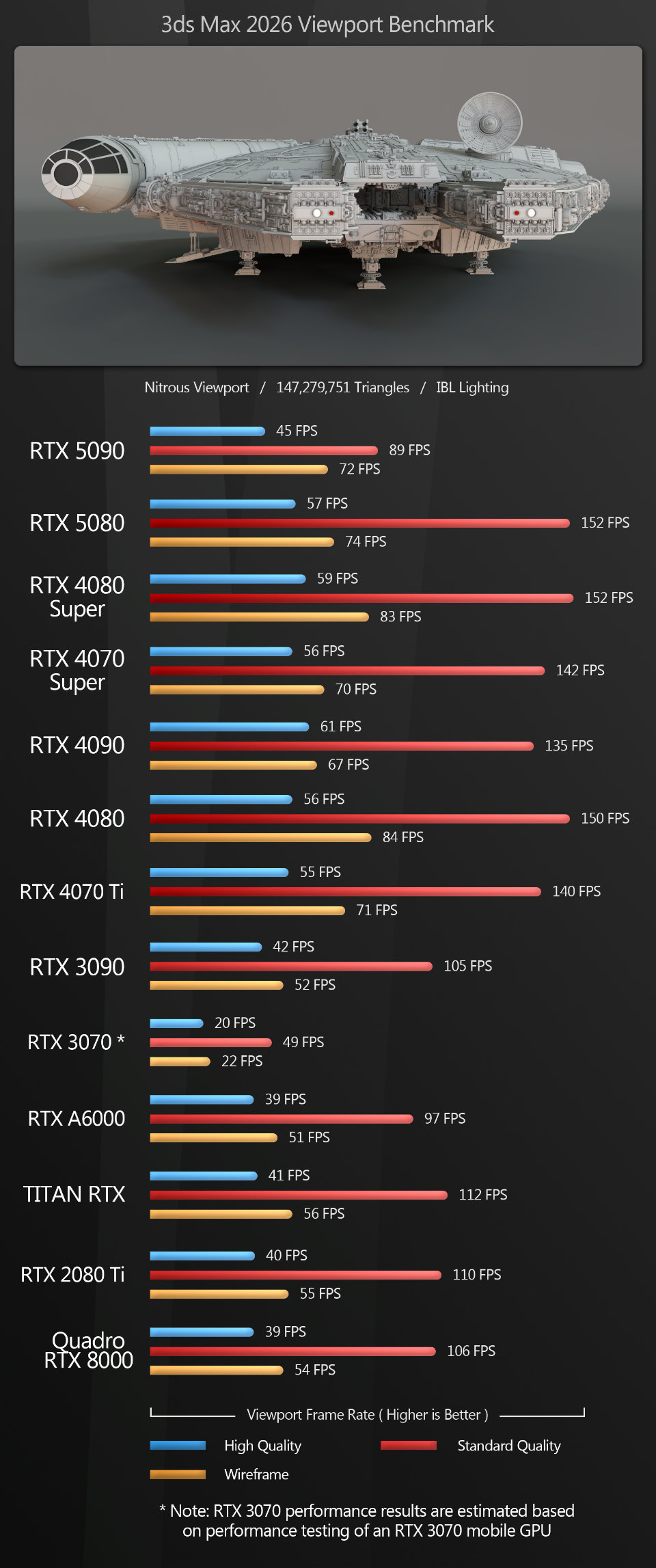

The viewport benchmarks include a number of key DCC applications – general-purpose 3D software like 3ds Max, Blender and Maya, specialist tools like Substance 3D Painter, CAD tools like Fusion, and real-time 3D applications like Unity and Unreal Engine.

The results are, frankly, all over the place, so rather than providing an overall summary, as I would usually do in these reviews, I’m going to go through them individually.

3ds Max The surprise here is the GeForce RTX 5090’s poor performance relative to the previous-generation Ada Lovelace GPUs, with viewport frame rates below those of the GeForce RTX 4070 Ti. The extra GPU memory alone should have given it a performance boost in this heavy scene, even over the 24 GB GeForce RTX 4090, but instead, we see the reverse.

The GeForce RTX 5080 pretty much matches the previous-gen 4080 Super, offering identical frame rates in shaded mode, and near-identical rates for wireframe and High Quality settings.

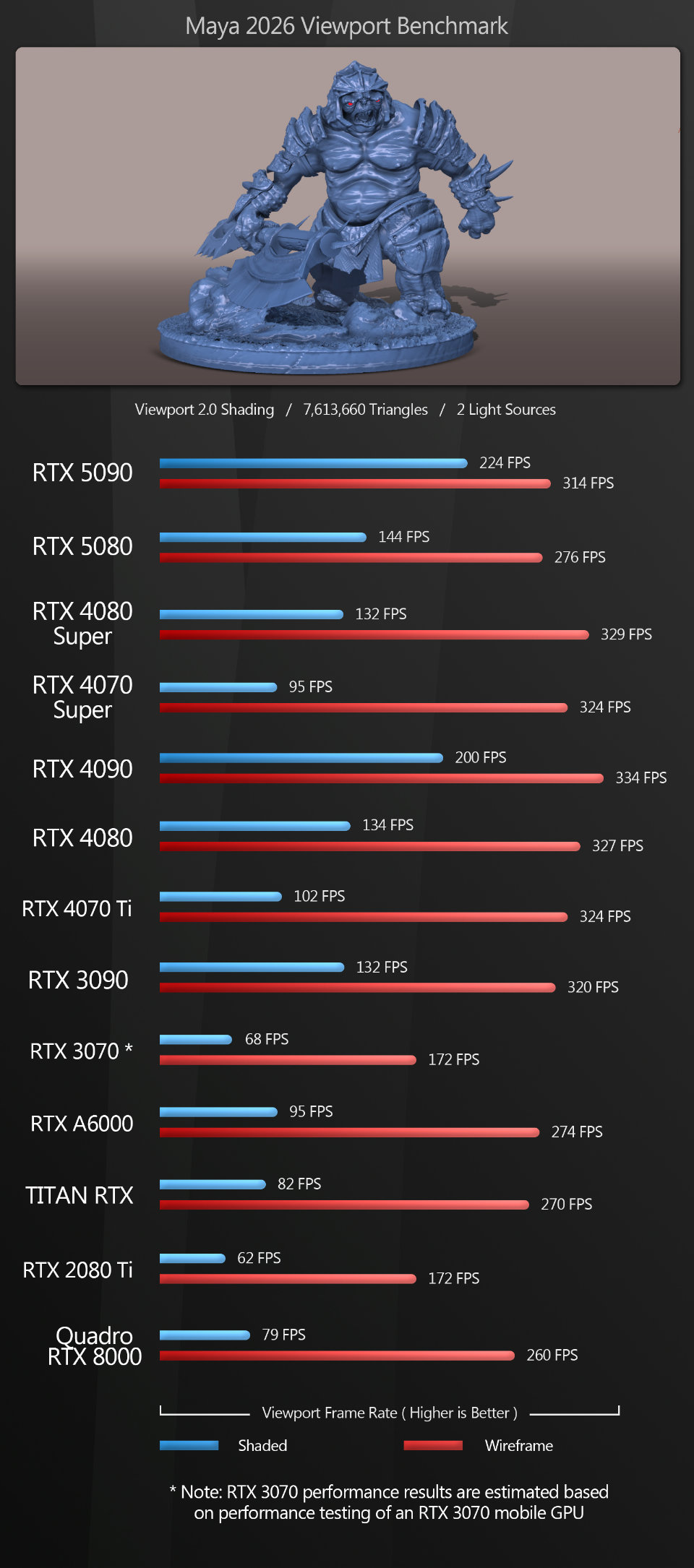

Maya The results here are more consistent than the 3ds Max scores, but still a bit surprising.

In shaded mode in Viewport 2.0, the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 do very well. The 5090 beats the previous-gen 4090 by a significant margin to take overall top spot, and the 5080 beats its previous-generation counterpart, losing out only to the 5090 and 4090.

But in wireframe mode, both the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 lose out to all of the GeForce 40 Series GPUs and even the two-generations-old GeForce RTX 3090.

Curious about this strange drop-off in performance, I tried switching Viewport 2.0 from OpenGL to DirectX, and while this only gave a small bump in frame rates in shaded mode (3-6fps on average), there was a massive jump in frame rates in wireframe mode.

So why haven’t I used those higher figures in the table above? Because DirectX is part of Windows. A lot of studios run Linux systems, where it isn’t an option. Many users don’t even know that Viewport 2.0 has a DirectX mode. Just be aware that if you do use Windows, switching to DirectX will net you a big increase in frame rates in wireframe mode.

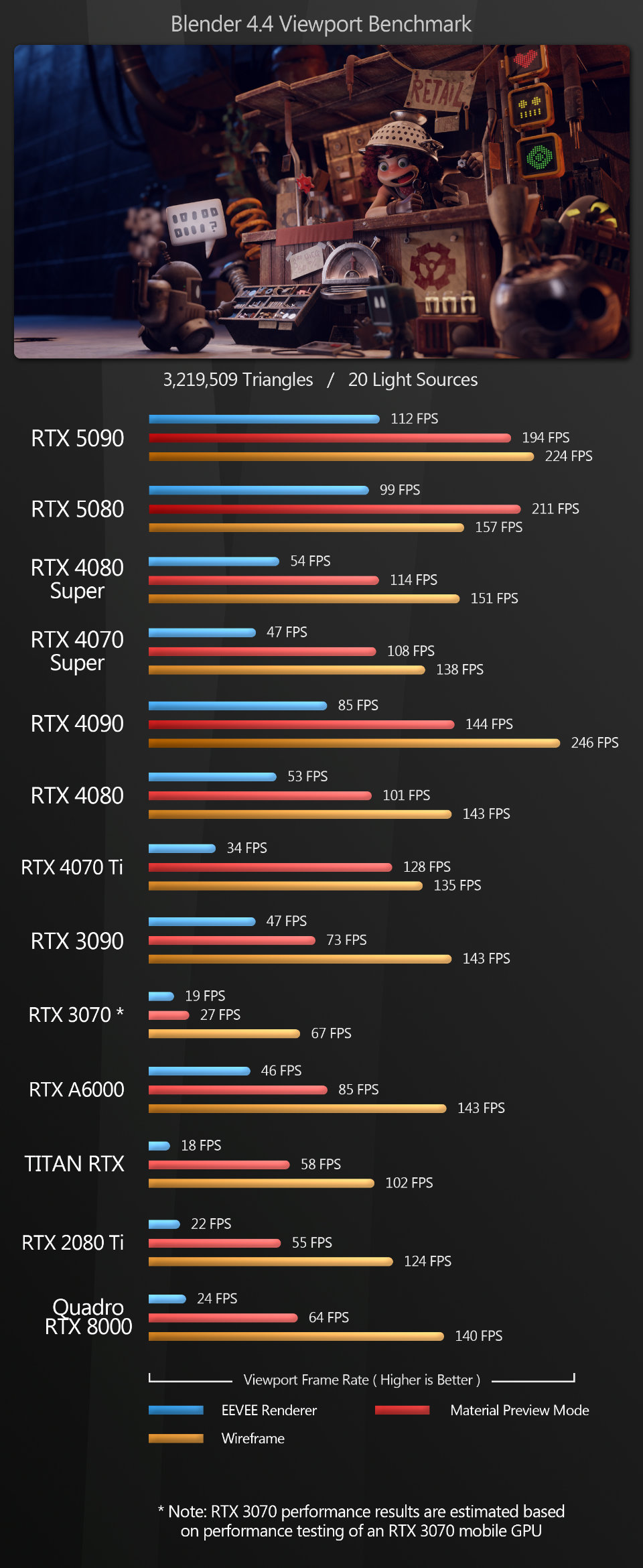

Blender Blender is the first test where the new Blackwell GPUs really shine across the different view modes. The GeForce RTX 5090 takes the top spot with the Eevee renderer by a very large margin, losing out only to the GeForce RTX 4090 in wireframe mode.

The GeForce RTX 5080 comes in just behind the 5090 with Eevee, but actually outperforms it in Material Preview mode. In wireframe mode, it too loses out to the GeForce RTX 4090, but beats all the other GPUs on test.

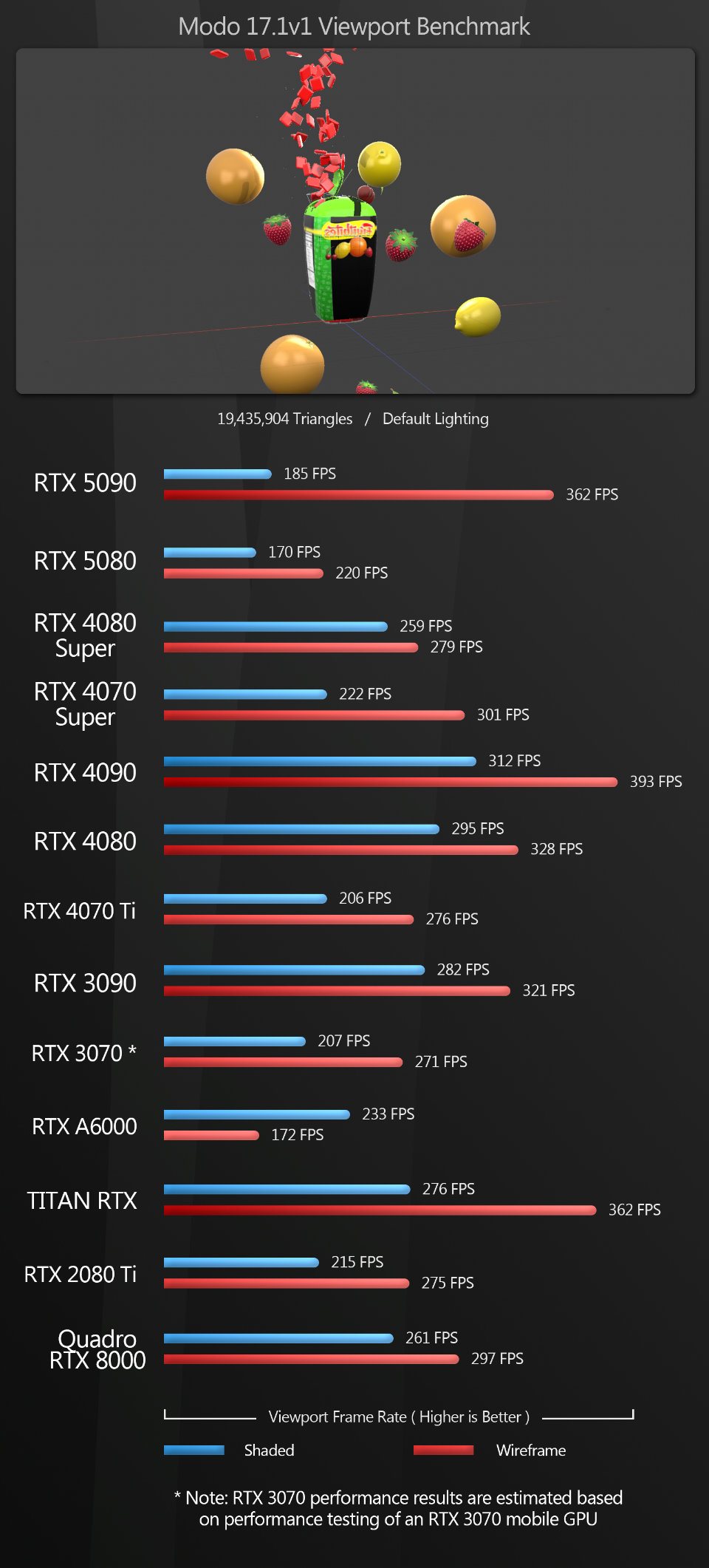

Modo With Modo, both the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 generate very low frame rates in shaded mode. In wireframe mode, the 5090 does quite well, only losing out to the 4090, but the 5080 posts the second-lowest score of any of the GPUs on test.

To be fair, these numbers are not surprising. Although Modo is still used for professional work, since Foundry ended development last year, it hasn’t been optimized for the Blackwell GPUs, and it’s unlikely that NVIDIA will put much work into optimizing its drivers for Modo either.

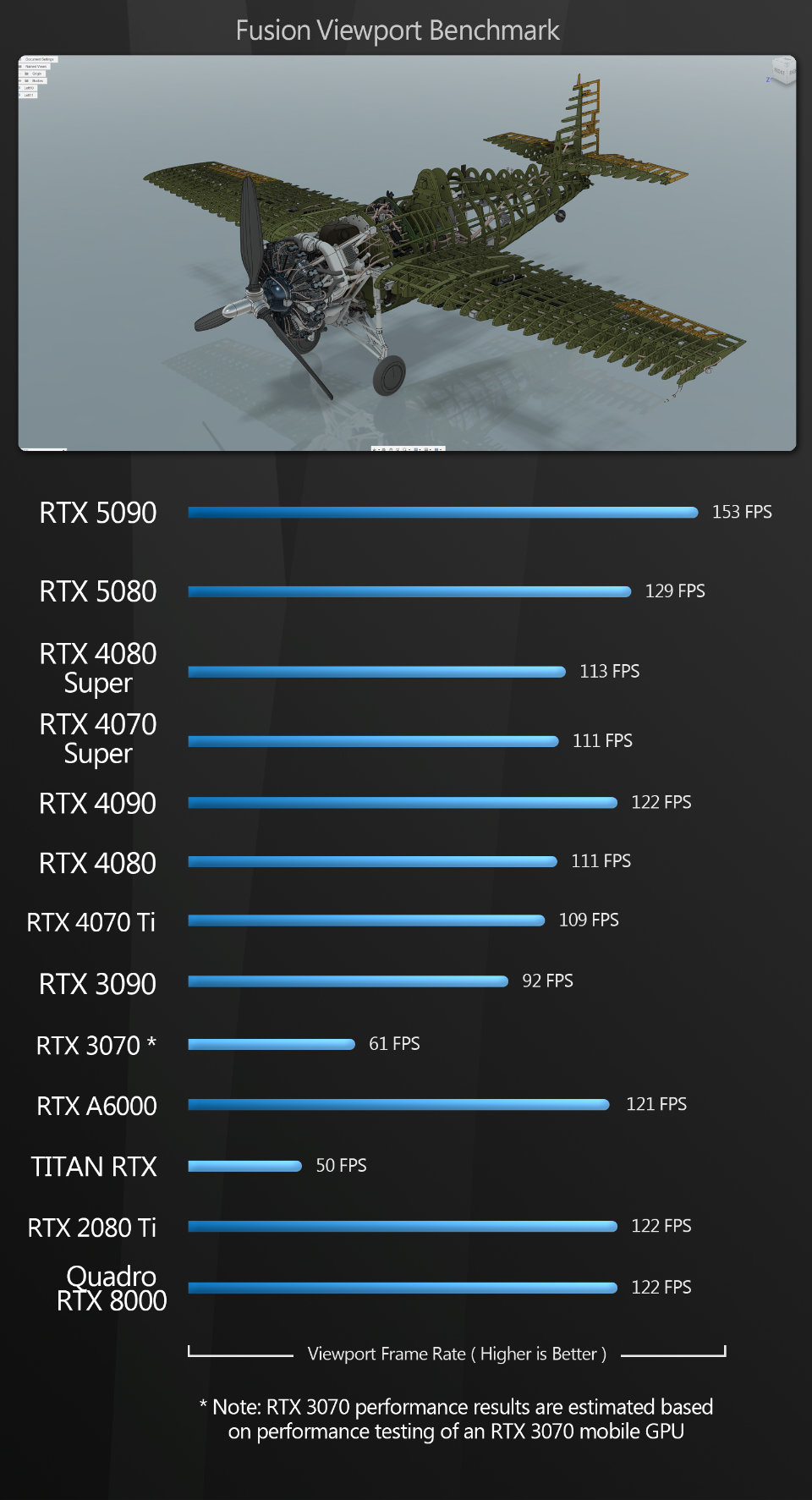

Fusion The Fusion scores speak for themselves. The GeForce RTX 5090 takes first place, and the 5080 second. No strange anomalies here, just a solid generational bump in performance.

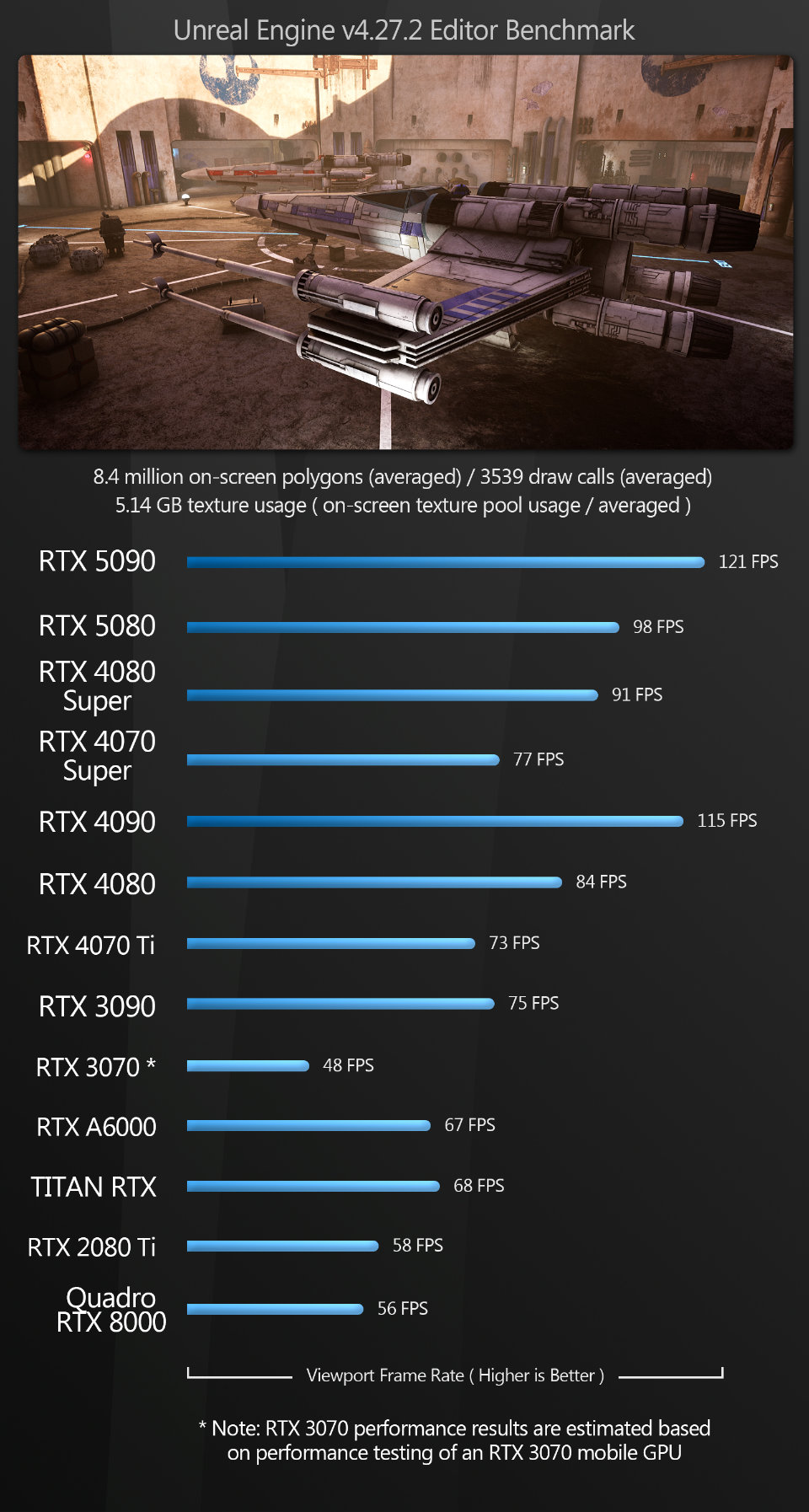

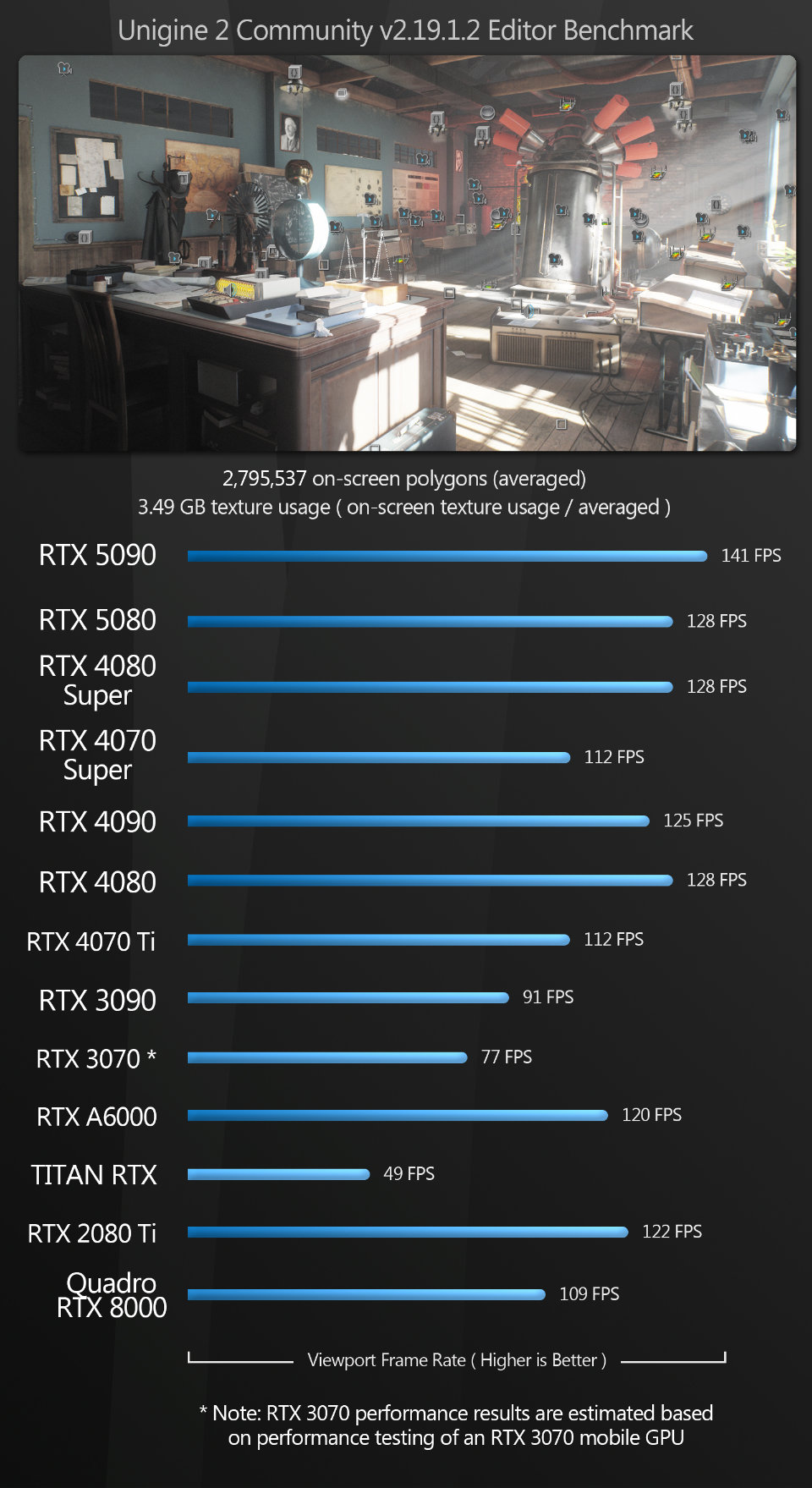

Unreal Engine The Unreal Editor benchmark follows a similar pattern to Fusion, with a significant increase in performance with both of the new GPUs.

Both the GeForce RTX 5090 and the 5080 take a commanding lead over the previous-gen GeForce 40 Series GPUs in the Unreal Engine 5.5 scenes; with Unreal Engine 4.37, we again see the 5090 taking the top spot, and the 5080 only losing out to the 5090 and the 4090.

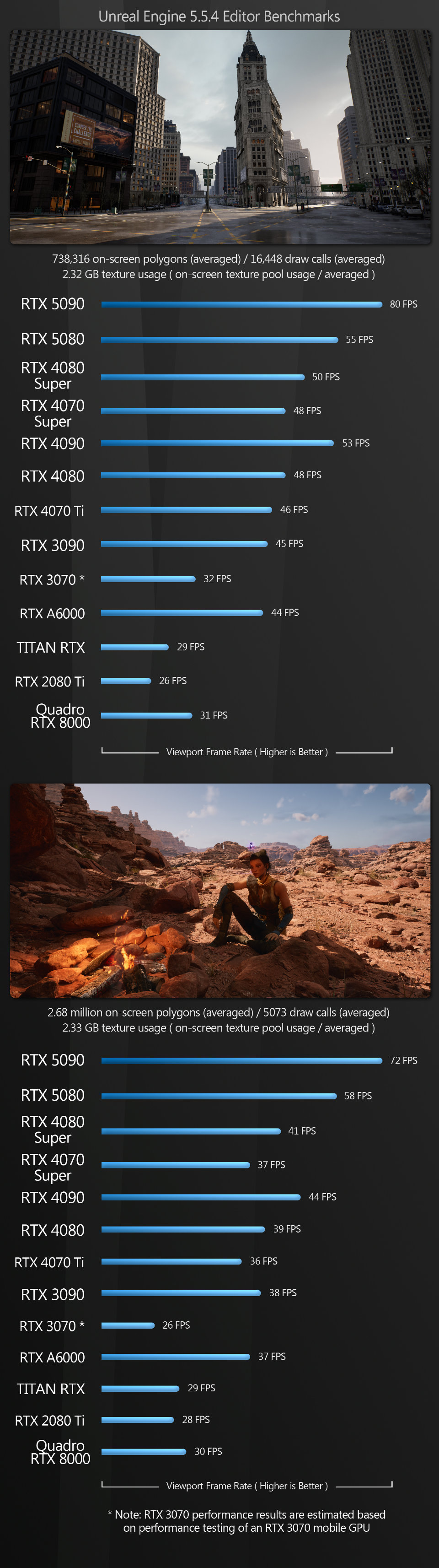

Unity Unity follows the same pattern as Fusion: the GeForce RTX 5090 takes first place, followed by the 5080, and all the previous-generation GPUs come in behind.

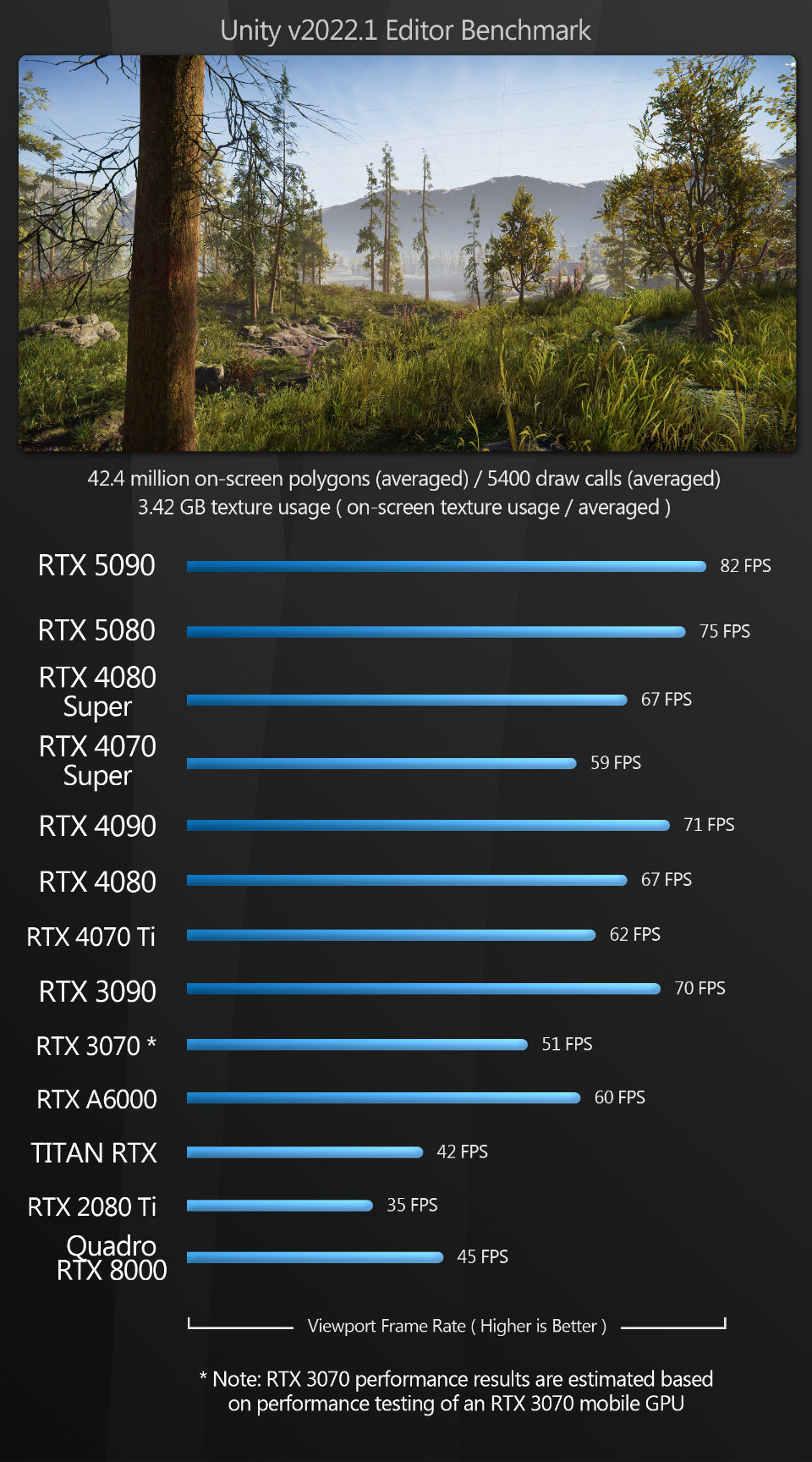

Unigine With Unigine, once again, the GeForce RTX 5090 takes the top spot. The 5080 ties with the 4080 Super and the 4080 for second place.

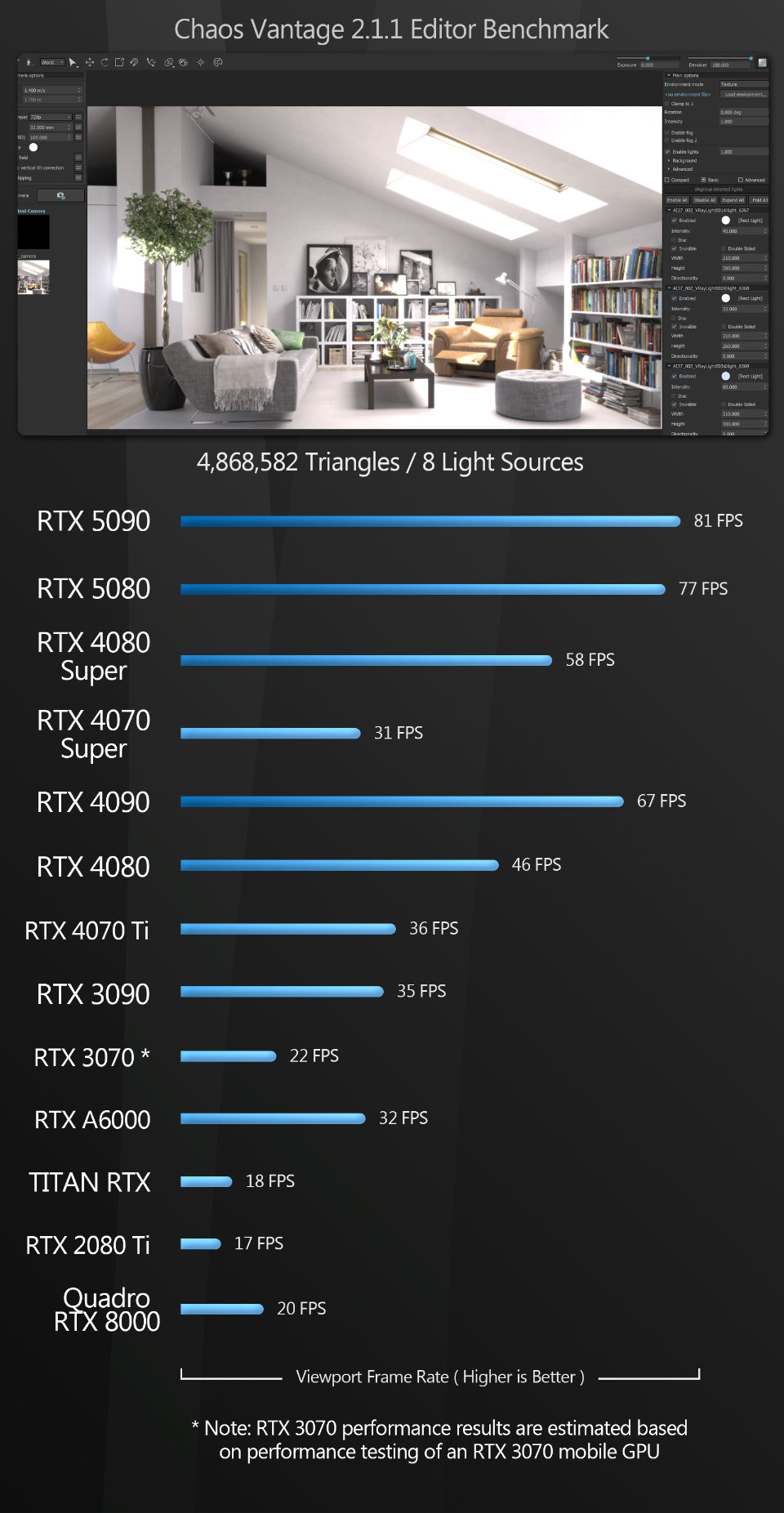

Chaos Vantage Vantage follows a similar pattern to Unigine, Unity and Unreal Engine. Both the GeForce RTX 5090 and the 5080 take a commanding lead over all the previous-gen GPUs.

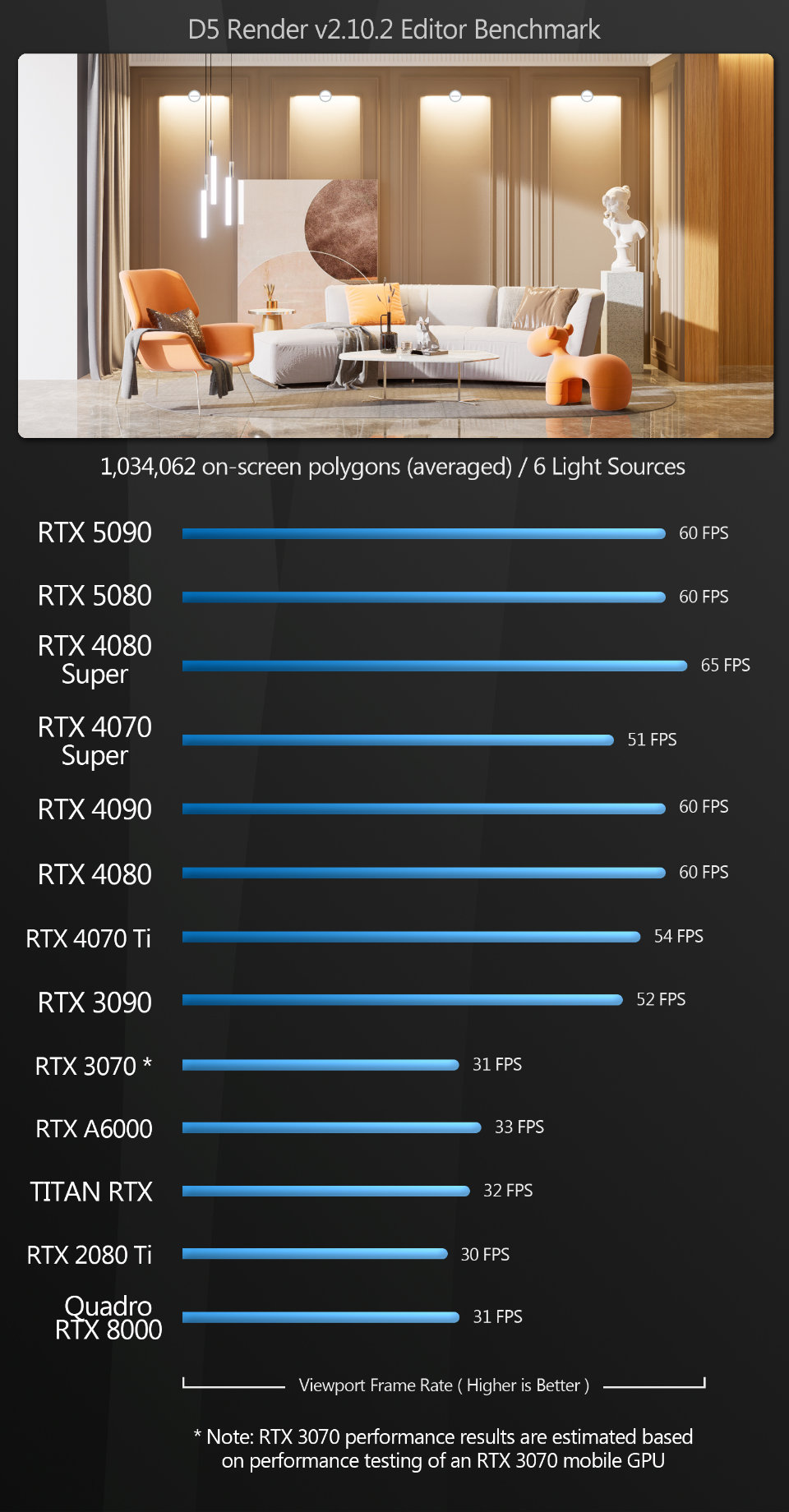

D5 Render The D5 Render benchmark generates some strange results, although both of the new Blackwell GPUs perform well.

With the exception of the GeForce RTX 4080 Super, the most powerful cards on test seem to be locked at the 60Hz refresh rate of the test system’s desktop monitor. Setting Vertical sync to Off or Fast in the NVIDIA Control panel, which renders the scene unconstrained on the GPU before sending it to the screen – and which works in other test applications – makes no difference here.

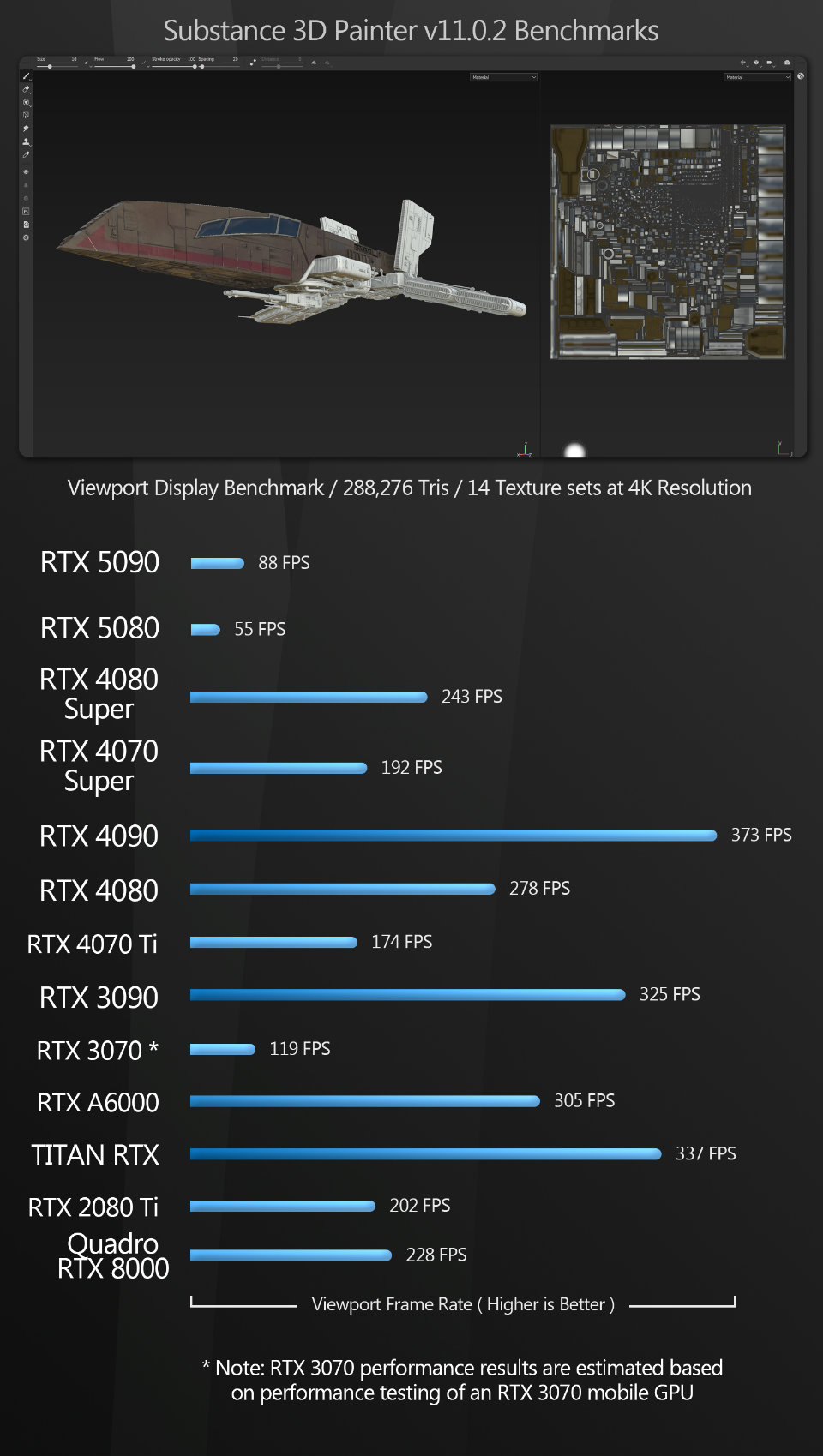

Substance 3D Painter Painter is another application that yielded very unexpected results. Viewport frame rate is significantly lower for the new Blackwell GPUs than all of the other GPUs on test. Even the seven-year-old GeForce RTX 2080 Ti easily beats the 5080 and 5080.

It’s worth noting that texture baking and smart material computation – which I also tested – are significantly faster on the 5090 and 5080 than they are on the GeForce RTX 40, 30 and 20 Series GPUs, so this may be a quirk that is resolved by a future driver update.

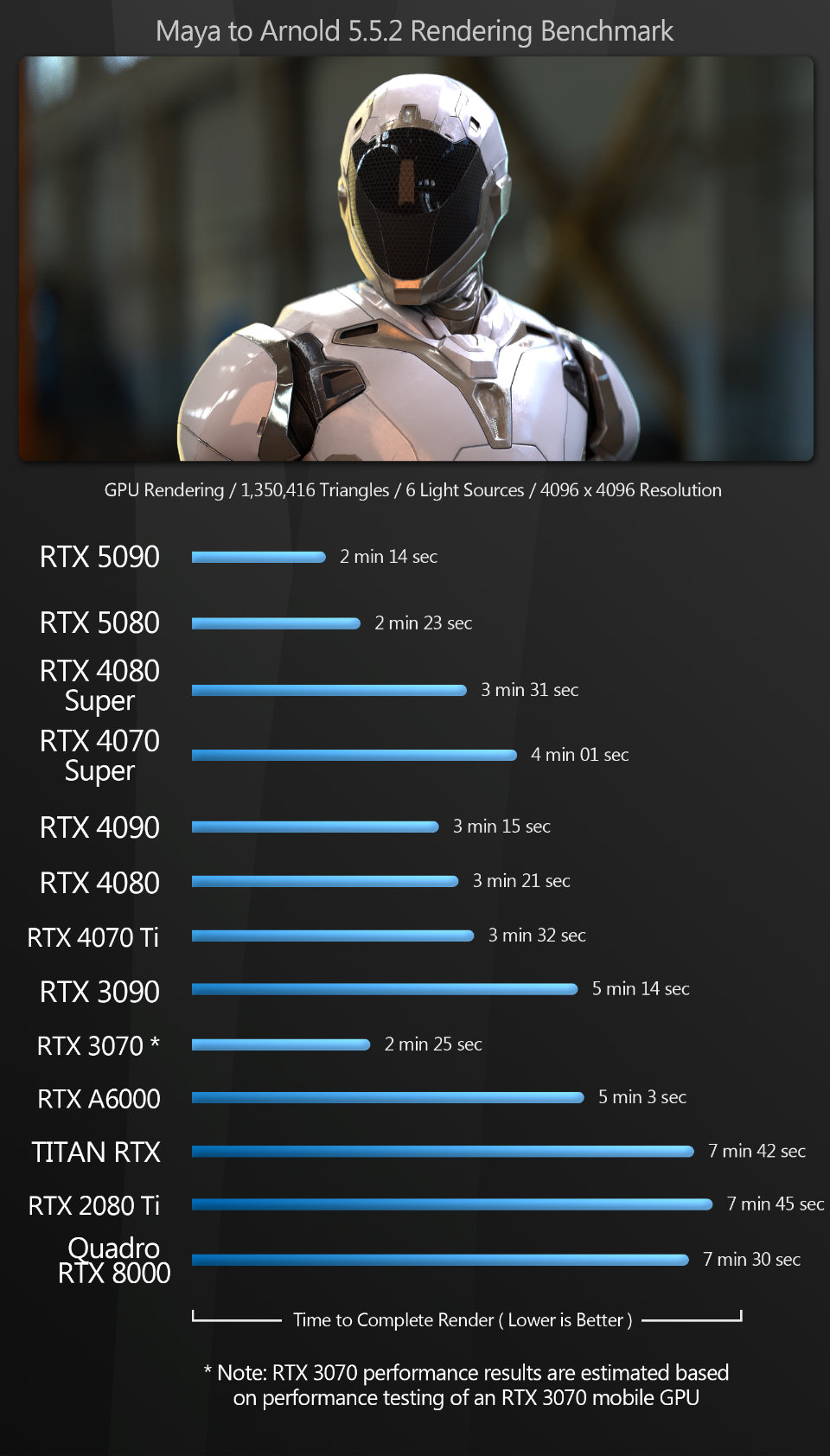

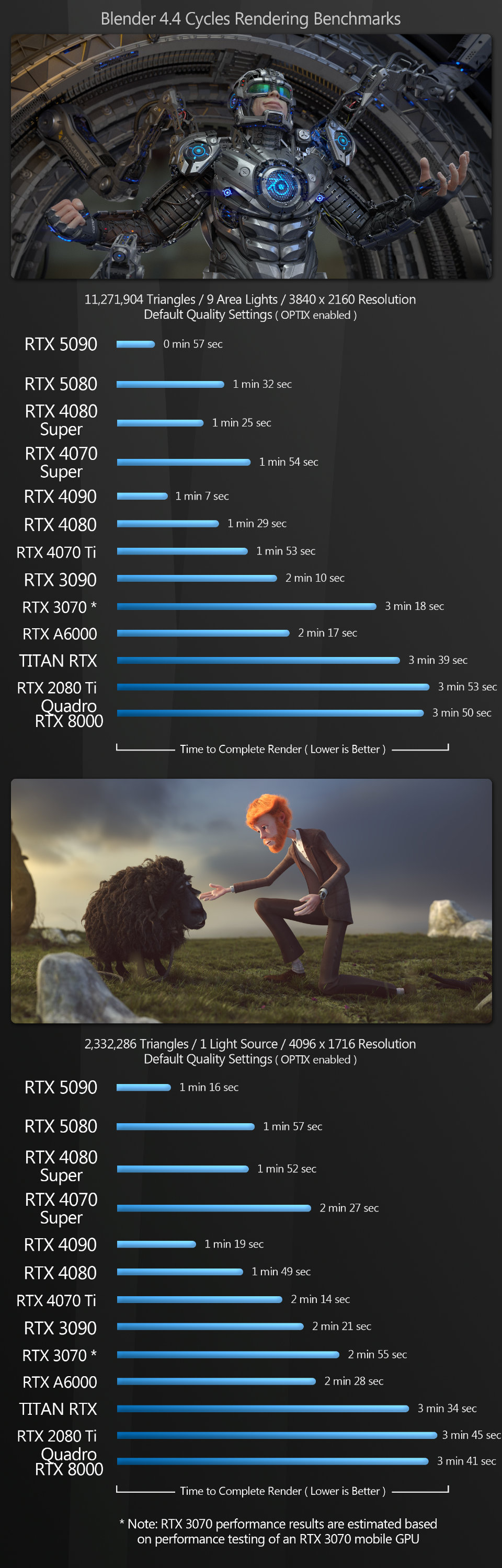

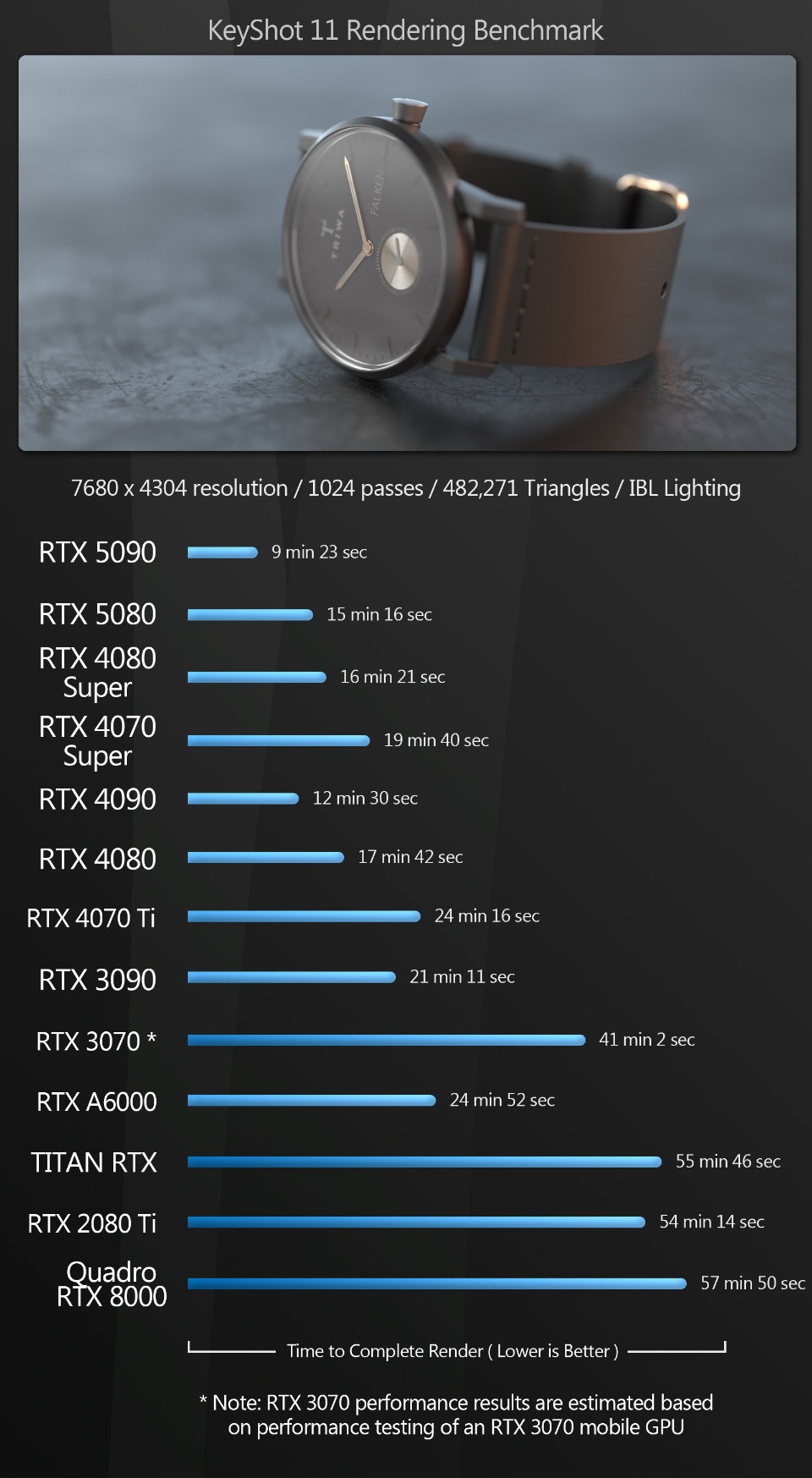

Rendering

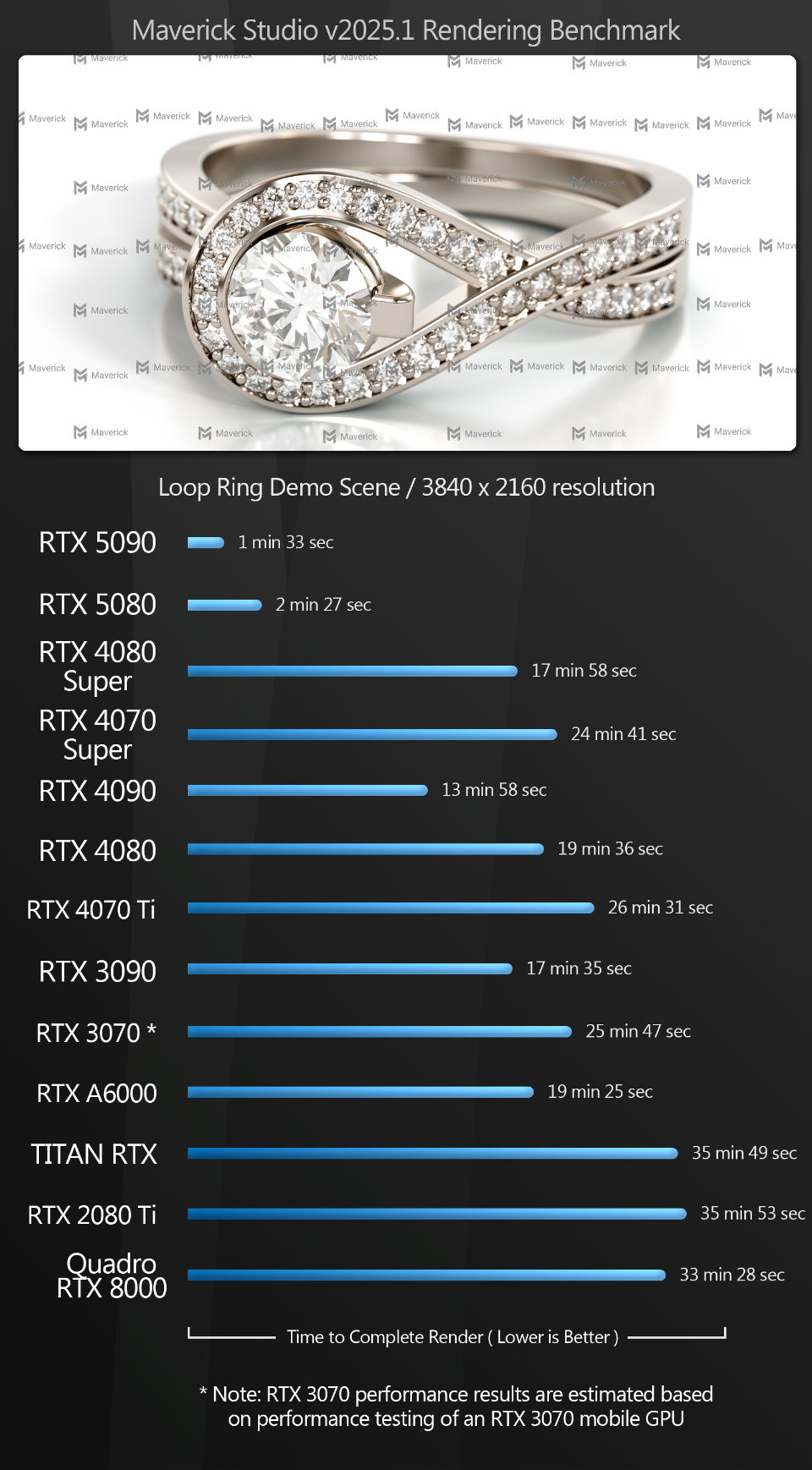

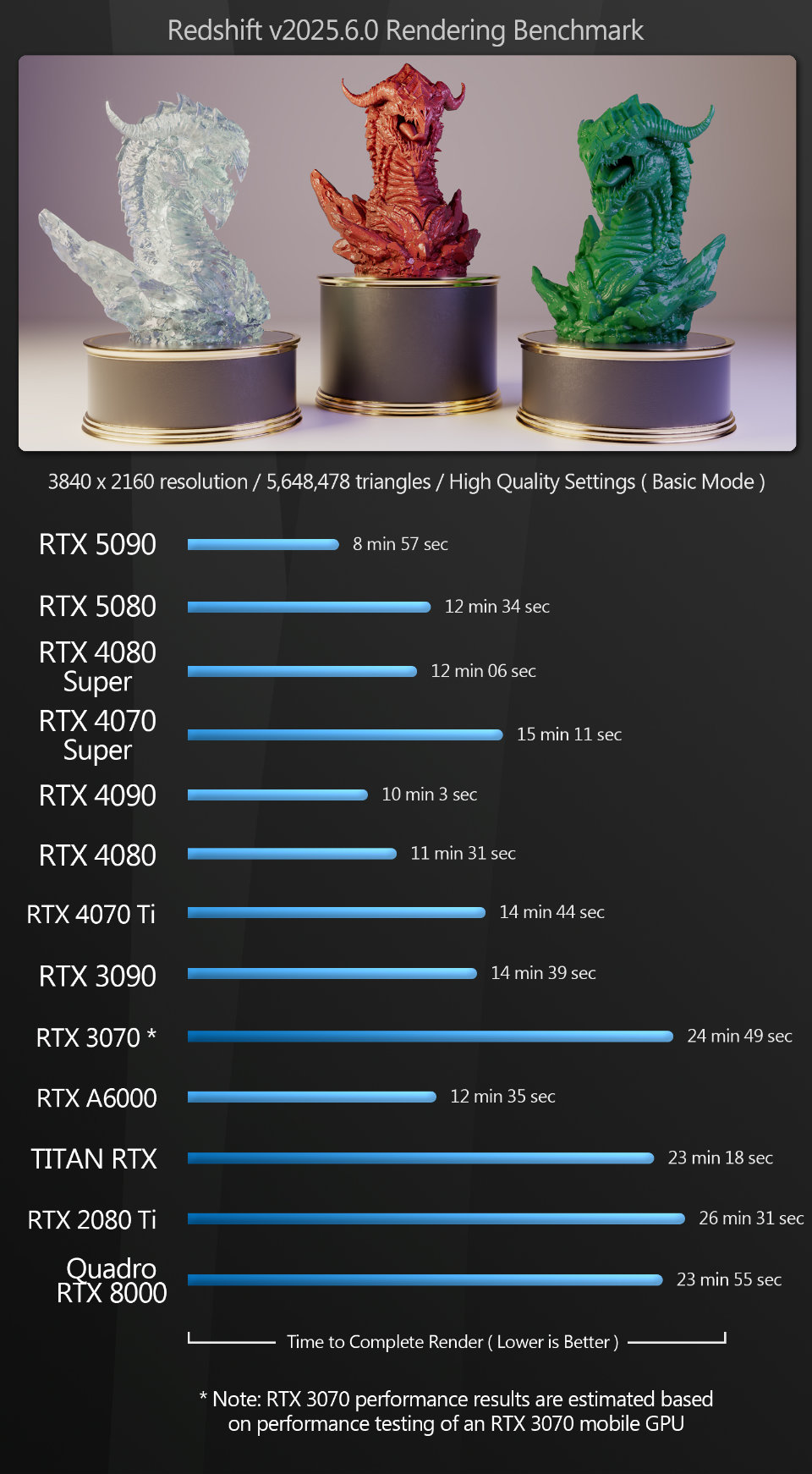

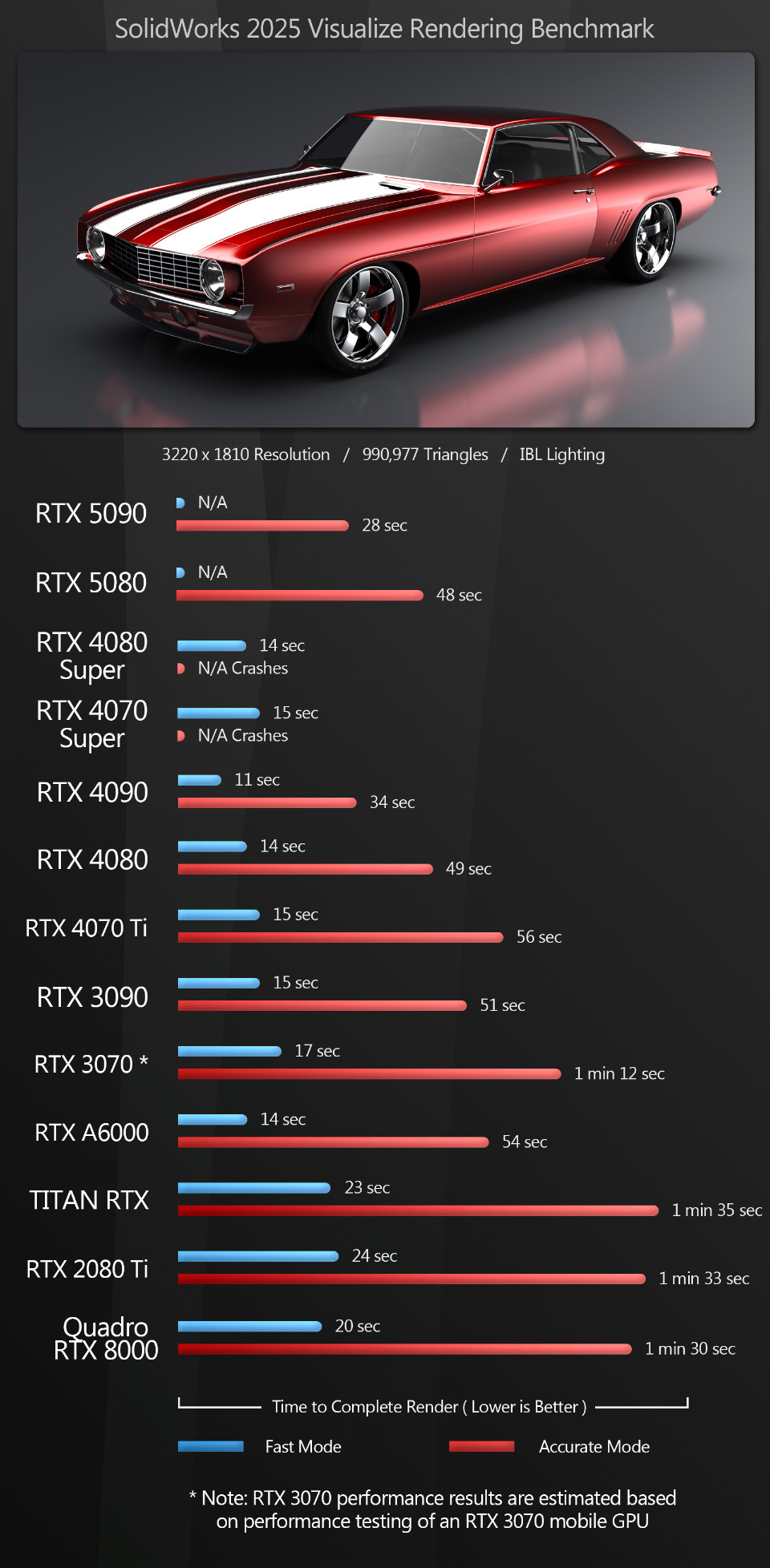

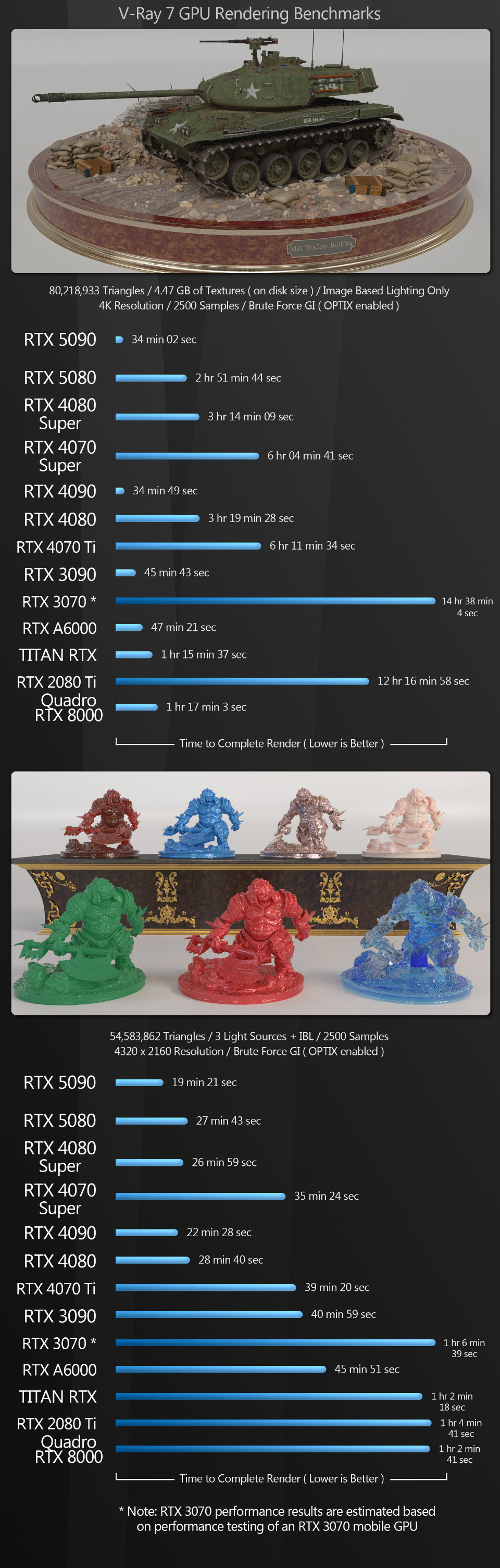

Next, we have a set of GPU rendering benchmarks, performed with an assortment of the more popular GPU renderers, rendering single frames at 4K or higher resolutions.

Compared to the viewport tests, the GPU rendering benchmarks give much more predictable, consistent results. The GeForce RTX 5090 wins all of the tests, while the 5080 hovers around the performance of the previous-gen GeForce RTX 4080 and 4080 Super, pulling slightly ahead in some tests, and falling slightly behind in others.

In the V-Ray tank scene, GPU memory is a key factor: all of the GPUs with more than 16 GB of VRAM render the scene much faster. Of the cards with 16 GB or less, the GeForce RTX 5080 performs best, but it’s beaten by the much older Titan RTX and Quadro RTX 8000.

Other benchmarks

The next benchmarks test the use of the GPU for more specialist tasks. Premiere Pro uses the GPU for video encoding; photogrammetry application Metashape uses the GPU for image processing and 3D model generation; and Houdini plugin Axiom and Cinema 4D’s Pyro solver both use the GPU for volumetric fluid simulation.

The GeForce RTX 5090 performs well in the specialist benchmarks, taking top spot in all tests.

The relative performance of the GeForce RTX 5080 jumps around a lot: in Metashape, the 5080 takes overall second place, but in Axiom and Premiere Pro, it falls behind several of the previous-generation GeForce RTX 40 Series cards. Although all come in within seconds of one another, the disparity would probably be greater with more complex projects.

The Cinema 4D Pyro test is another illustration of the benefit of additional graphics memory for complex CG work. The simulation tops out at around 30 GB, slowing to a crawl once GPU memory is exhausted, so only the GeForce RTX 5090 and the older GeForce RTX A6000 and Quadro RTX 8000 offer performance that would be considered usable in production.

Synthetic benchmarks

Finally, we have an assortment of synthetic benchmarks. They don’t accurately predict how a GPU will perform in production, but they’re a decent measure of its performance relative to other GPUs, and the scores can be compared to those available online for other cards.

The synthetic test scores are pretty much in line with expectations. The GeForce RTX 5090 takes top spot in all of them, with the 5080 coming second in the V-Ray benchmark, and third, behind the 5090 and the previous-gen GeForce RTX 4090, in the others.

Other considerations

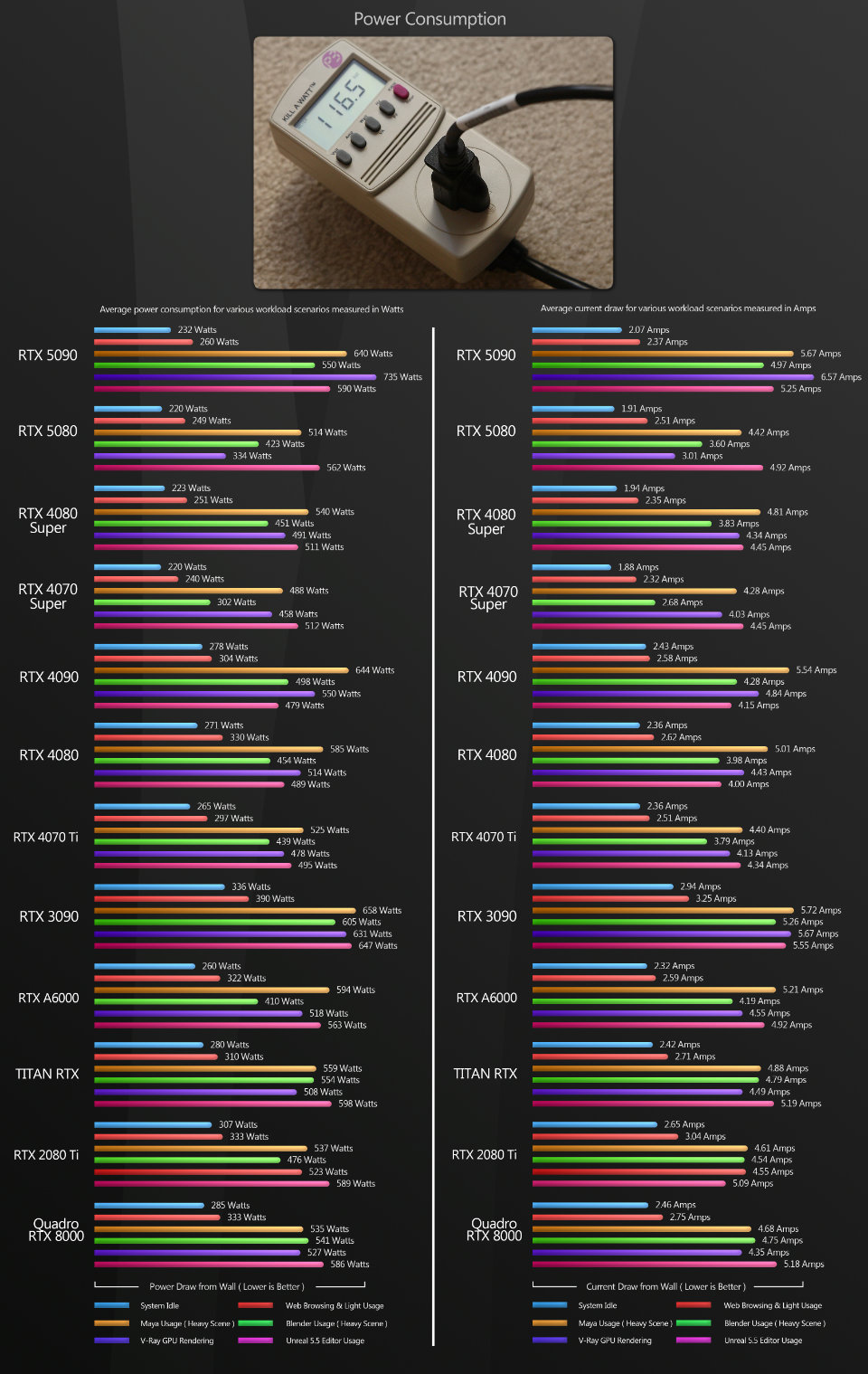

Power consumption

To test the power usage of the GPUs, I measured the power consumption of the entire test system at the wall outlet, using a P3 Kill A Watt meter. Since the test machine is a power-hungry Threadripper system, my figures will be higher than most DCC workstations.

As well as power, I measured current drawn. Current is often overlooked by reviewers, but it can be a critical determinant of how many machines you can run on a single circuit.

Most US houses run 15A circuits from the main panel, and many circuit breakers are rated for 80% of their maximum load, so a 15A circuit with a standard breaker should not exceed 12A for continuous usage. In my tests, the current drawn by the test system approached 6A when the more power-hungry GPUs were installed. If the wall outlets in your home office are connected by a single circuit, this could determine whether you can run two workstations simultaneously, particularly when you factor in monitors and lights.

For the most part, despite their greater number of CUDA cores, the GeForce RTX 5090 and 5080 use less power for the same tasks than their previous-generation counterparts.

However, there are a few notable exceptions. In Unreal Editor and V-Ray GPU, the GeForce RTX 5090 consumes significantly more power than the previous-gen 4090; and the 5080 also consumes more power than the previous-gen 4080 and 4080 Super in Unreal Editor.

Drivers

Finally, a note on the Studio Drivers with which I benchmarked the GeForce RTX GPUs. NVIDIA now offers a choice of Studio or Game Ready Drivers for GeForce cards, recommending Studio Drivers for DCC work and Game Ready Drivers for gaming. In my tests, I found no discernible difference between them in terms of performance or display quality. My understanding is that the Studio Drivers are designed for stability in DCC applications, and while I haven’t had any real issues when running DCC software on Game Ready Drivers, if you are using your system primarily for content creation, there is no reason not to use the Studio Drivers.

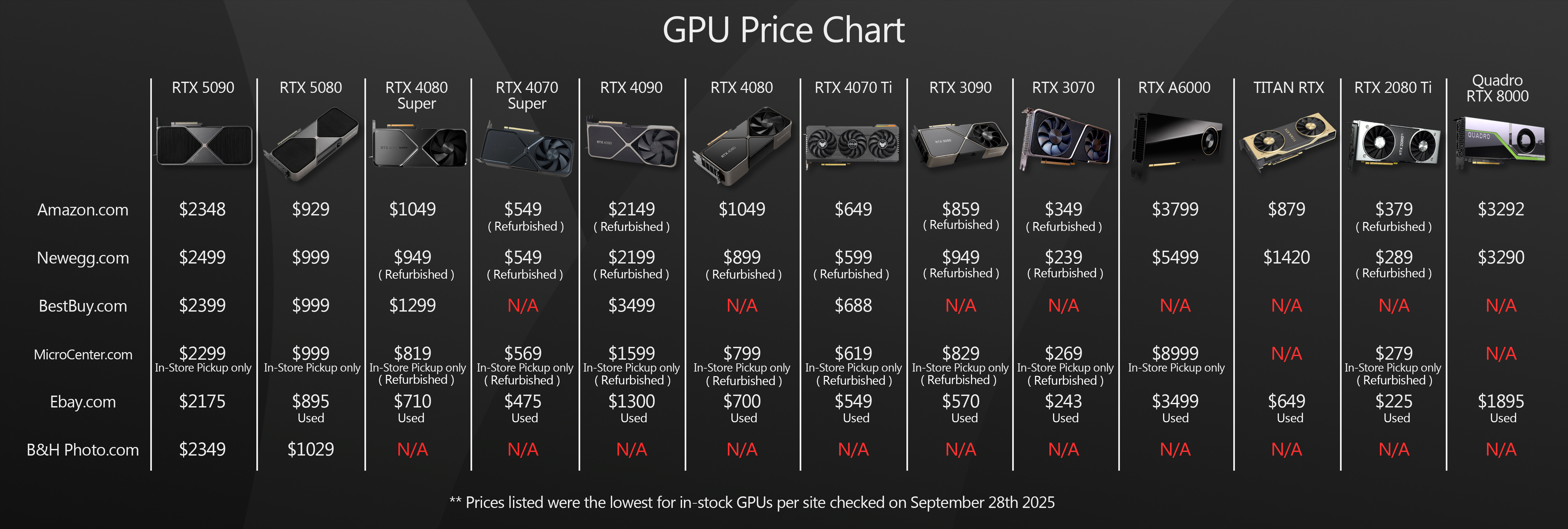

Click the image to view it full-size.

Prices

Next, some thoughts on pricing. Let’s start with the GeForce RTX 5090. It has a MSRP of $1,999: a significant jump from the GeForce RTX 4090, which had a MSRP of $1,599 on its release three years ago. As a gaming GPU, its price tag is pretty steep, but as a workstation GPU, it looks a much better deal: in most of my tests, it provided a moderate performance bump over the 4090, and it has significantly more graphics memory: 32 GB as opposed to 24 GB.

However, the MSRP is just the theoretical price that NVIDIA suggests that companies will sell the GeForce RTX 5090 for. Sadly, reality is currently very different. The launch of the 5090 coincided with a massive explosion in demand for GPUs with machine learning cores to fuel the current frenzy in the deployment of AI data centers. This has caused prices to soar and stocks to dwindle, much as the crypto mining boom did for the GeForce RTX 30 Series GPUs.

Although things aren’t as bad as they were six months ago, it’s still pretty near impossible to find a GeForce RTX 5090 at anywhere close to its MSRP, as you can see from the image above, which shows a snapshot of the prices in online stores at the time this review was completed.

Next, the GeForce RTX 5080. It has a MSRP of $999: the same launch price as the previous-gen GeForce RTX 4080 Super. This makes sense: the 5080 has the same 16 GB of graphics memory, and provided only slight performance improvements over the 4080 Super in my tests.

It’s also possible to pick up a GeForce RTX 5080 much closer to the MSRP: as I completed this review, there was even one selling on Amazon.com for $929 with a two-week lead time.

Verdict

As usual, there is a lot of data to digest here, so let me take a stab at breaking it down for you.

Let’s start with the GeForce RTX 5090. It beat the previous-generation Ada Lovelace GPUs by a large margin in some of my tests; by a smaller margin in others; and even in those tests where it lost out to the older GeForce RTX 4090 or 4080, it still performed at a perfectly acceptable level. As software developers figure out how to make better use of the Blackwell architecture, and NVIDIA refines its drivers, I’d also expect some of the outlying scores to improve.

From a pure performance standpoint, I feel comfortable recommending the RTX 5090 as my current top pick for a GeForce GPU for content creation, particularly given its 32 GB of graphics memory, which makes it much more versatile and future-proof than previous-generation cards.

The thing I wrestle with is the cost. If you could actually get a GeForce RTX 5090 for its MSRP of $1,999, this would be a no-brainer, hands-down, buy-it-now recommendation, but with AI holding GPU prices hostage, the decision is more complex.

The first thing to consider is that the alternatives may not be that much cheaper. Logic suggests that used GeForce RTX 4090s should be quite affordable, as (a) they’re used, and (b) resale prices for PC hardware fall off a cliff faster than Thelma and Louise’s 1966 Ford Thunderbird. Unfortunately, logic does not prevail here. If anything, the RTX 4090 seems to have appreciated in value, with many currently selling online for $1,700 to $2,000: well above their original MSRP. If prices for used 4090s were to fall into the $900 to $1,200 range, that would make them very attractive alternatives to the GeForce RTX 5090, but that isn’t currently the case.

The second thing to consider is that prices for the 5090 itself have come down… a bit. While many currently sell online for around $3,000, a few months ago, they were selling for over $4,000, so if you’re willing to wait a bit longer, prices may come down still further.

There are a few online retailers listing the 5090 at its MSRP of $1,999, and while they’re almost always out of stock, if you spot a 5090 in the few milliseconds between a store resupply and it selling out once more, grab it and don’t look back. Even around the $2,500 mark, the 5090 isn’t a bad deal. But personally, I wouldn’t buy one for more than that.

As for the GeForce RTX 5080, it follows pretty much the same pattern as the 5090, although not to such extremes. In my tests, the 5080 performed quite similarly to the previous-generation 4080 Super, with some scores higher, some lower. Unlike the 4080 Super, it is a two-slot GPU, and it’s a bit more power-efficient, but the Blackwell GPUs lean heavily on their new AI features for improved performance in games, and most DCC applications don’t make use of them yet.

Unfortunately, like the GeForce RTX 5090, the 5080 suffers from price inflation, with many currently selling online for $1,100 to $1,200. That isn’t a horrible mark-up, but if you’re looking to save a few bucks, you can currently find used 4080 Supers in the $800 to $900 range, and if you can get one in good condition, it may be worth considering.

To sum up: once again, NVIDIA has released new GPUs with an overall improvement in performance over its previous generation of cards. It’s not quite the massive jump we saw going from the Ampere-era GeForce RTX 3080 and 3090 to the Ada Lovelace GeForce RTX 4080 and 4090, but it’s still pretty good. However, NVIDIA and the DCC software developers still need to work together to fix some of the weird performance discrepancies I observed in my tests, particularly with viewport frame rates, and NVIDIA needs to address its supply issues to bring prices back down – at the very least, to the MSRPs for the new cards.

Lastly, I want to thank you for taking the time to stop by. I hope this review has been helpful, and if you have any questions or suggestions, let me know at the email address below.

Links

Read more about the GeForce RTX 50 Series GPUs on NVIDIA’s website

About the reviewer

Jason Lewis is a Senior Hard Surface Artist at Lightspeed LA, a Tencent America development group, and CG Channel’s regular hardware reviewer. You can see more of his work in his ArtStation gallery, and contact him by email here.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the following people for their assistance in bringing you this review:

Stephenie Ngo of NVIDIA

Sean Killbride of NVIDIA

Stephen G Wells

Adam Hernandez

Have your say on this story by following CG Channel on Facebook, Instagram and X (formerly Twitter). As well as being able to comment on stories, followers of our social media accounts can see videos we don’t post on the site itself, including making-ofs for the latest VFX movies, animations, games cinematics and motion graphics projects.