Review: Asus ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED laptop

Can a mobile workstation really hold up against a similarly specified desktop system in production? Jason Lewis puts one of Asus’s new Nvidia Studio mobile systems through an array of real-world tests to find out.

In this review, we are going to be taking a look at a mobile workstation built upon the Nvidia Studio platform, the Asus ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED. It has been quite some time since I have had the opportunity to test a mobile system tailored to graphics work (the last time was back in 2015 with the HP ZBook 17 G2) so I was curious to see how seven years of technical advances have shaped mobile workstations.

This review is broken up into two parts, the first focusing on the system, and the second on Nvidia Studio itself. But first, let’s address a question that artists have been asking since mobile workstations first became available: is it better to use a desktop or mobile system for professional graphics work?

I have touched on this in previous reviews, and the answer always depends on your needs as an artist. Back in 2015, my conclusion was: if you need to be portable, a mobile workstation can be a viable alternative to a desktop system, albeit at a slightly higher price. If you need the absolute fastest system you can get, or if upgradeability is important, you’re better off with a desktop. But does the same hold true today?

Jump to another part of this review

System specifications

Testing procedure

Benchmark results

Other considerations

The Nvidia Studio platform

Verdict

System specifications

For mobile systems, Nvidia Studio laptops have pretty impressive specs. When I started reviewing mobile workstations in the early 2010s, four-core CPUs were the best you could hope for. Today, some systems go as high as 16 CPU cores. Pair that with the current Nvidia RTX GPUs (at the time this review was written, the GeForce RTX 30 Series, but since updated to the 40 Series), and you have a recipe for performance.

The Asus ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED we are looking at here isn’t Asus’s top-of-the-range mobile system, but it’s still pretty powerful, sporting an eight-core AMD Ryzen 9 5900HX CPU running at 3.3 GHz (with a maximum boost speed of 4.6 GHz), and a Nvidia GeForce RTX 3070 mobile GPU in addition to the Radeon Vega GPU on the 5900HX die. For memory, the Studiobook 16 is equipped with 32GB of 3,200MHz DDR4 RAM in a 2 x 16GB configuration, and for storage, 2 x 1TB PCIe 4.0 M.2 SSD drives in a RAID 0 configuration.

For all of the high-performance hardware packed into it, the Studiobook 16 is remarkably thin: about half the thickness of the HP ZBook 17 I looked at in 2015. It’s heavier than it looks – the weight caught me off guard the first time I picked it up – but it’s still significantly lighter than the ZBook.

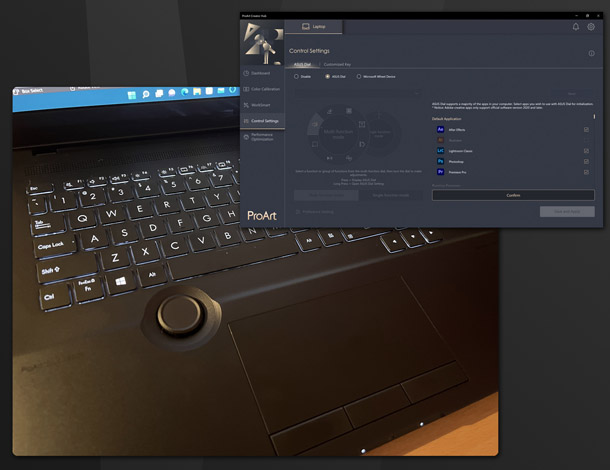

Flipping up the screen reveals a pretty standard back-lit mobile-format keyboard with thin, short-throw keys, a generously sized trackpad, and the Asus Dial, a mechanical wheel that controls various functions in DCC applications. It can be mapped to custom shortcuts through Asus’s ProArt Creator Hub app.

Connectivity is decent: not the best I have seen in a mobile system, but not the worst either, with two full size USB 3.2 Gen2 Type-A ports, two USB 3.2 Gen2 Type-C ports, a HDMI 2.1 port, a RJ45 Ethernet port, a 3.5mm audio jack, a SD Express 7.0 card reader and the DC power input. These compete for space along the sides of the system with a pair of rather large cooling exhaust vents.

The Studiobook 16 also includes a standard-fare HD webcam built into the top of the display bezel, but unlike many mobile systems, it has a built-in privacy shutter: a nice touch.

This particular configuration has a 16-inch 4K OLED display with a resolution of 3,840 x 2,400px in a 16:10 aspect ratio. It’s DisplayHDR 500 True Black-certified, with a 1,000,000:1 contrast ratio and a peak brightness of 550nits, runs at 60Hz with a 0.2ms response time, displays up to 1.07 billion colours (a colour gamut of 100% DCI-P3 or 133% sRGB), and is Pantone-validated.

Testing procedure

On paper, the Studiobook 16 should be able hold up to a lot of desktop systems without breaking a sweat. To test that theory, I benchmarked it against a desktop system with similar specs: a Dell XPS workstation with a 10-core Intel Core i9-10900K running at 3.7GHz (with a maximum boost speed of 5.3GHz), a Nvidia GeForce RTX 3070 GPU, 64GB of 3,200MHz DDR4 RAM, and a 2TB PCIe 3.0 M.2 SSD drive.

The desktop system has an advantage in CPU clock speed and two extra CPU cores, but the Studiobook has faster storage. (The desktop system also has double the memory, but as long as our benchmark tests don’t exceed 32GB, the extra RAM shouldn’t have much effect on performance.) The most interesting comparison is going to be how Studiobook’s GeForce RTX 3070 mobile GPU stacks up to its desktop counterpart.

For testing, I used the following applications:

Viewport performance

3ds Max 2023, Blender 3.2.1, Chaos Vantage 1.6.2, Maya 2023, Substance 3D Painter 8.1.1, Unreal Engine 5.0.3

Rendering

Blender 3.2.1 (using Cycles, tested on CPU and GPU), Corona 8 for 3ds Max (CPU only), Arnold (via MtoA 5.1.0, using Arnold GPU), V-Ray 6 for 3ds Max (using V-Ray GPU)

Other benchmarks

Axiom 2.1 for Houdini, Metashape 1.8.2, Premiere Pro 2022, World Machine 4027

Synthetic benchmarks

3DMark, Cinebench R23, OctaneBench 2020

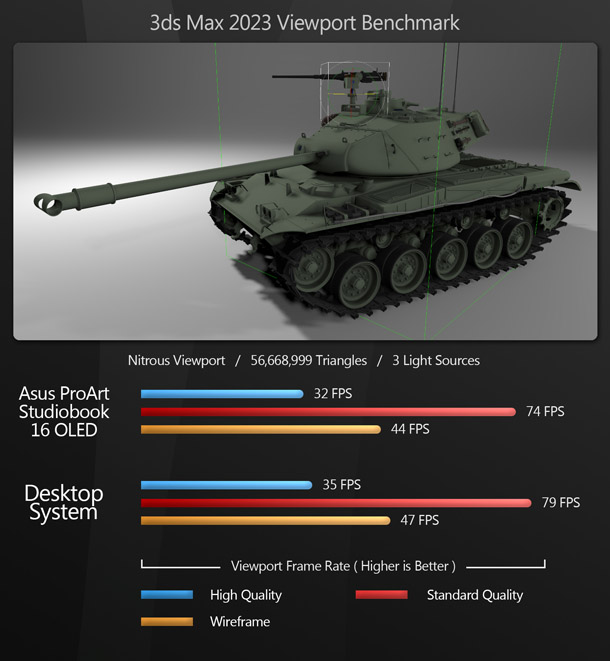

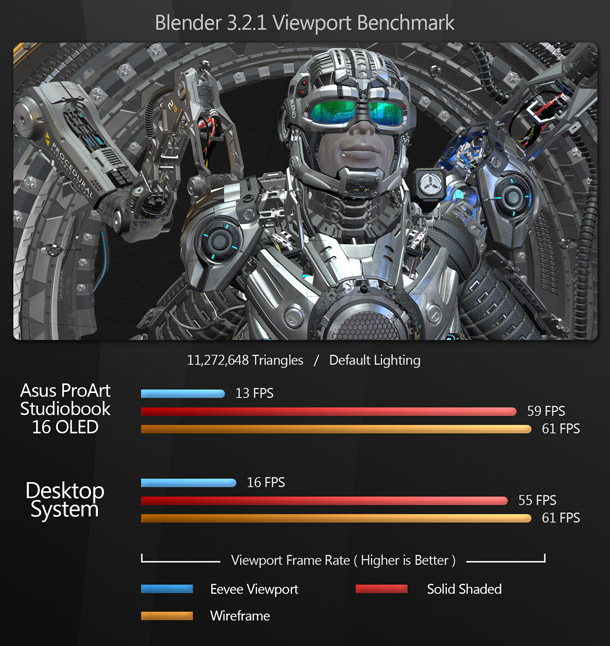

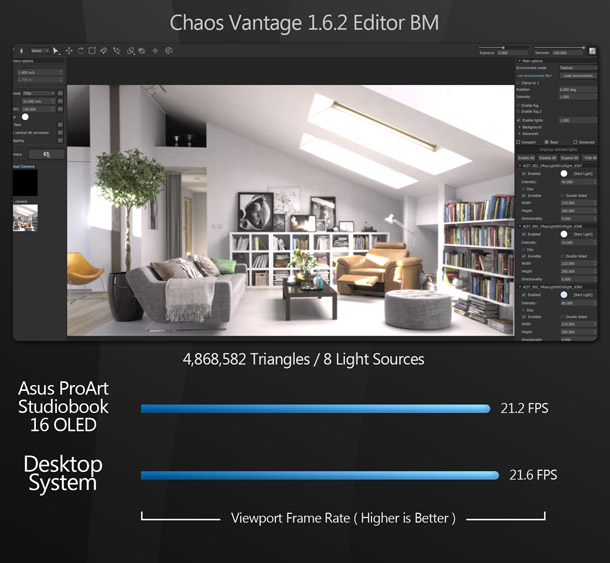

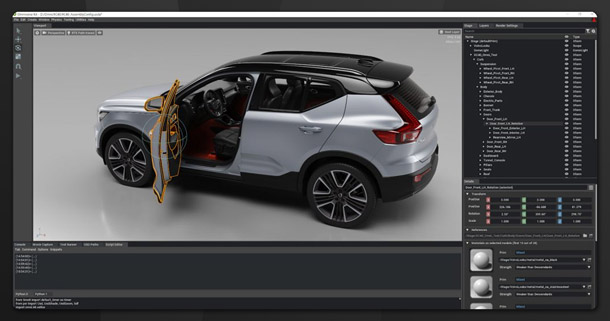

In the viewport benchmarks, the frame rate scores represent the figures attained when manipulating the 3D assets shown, averaged over five testing sessions to eliminate inconsistencies. Testing was performed at 60Hz at the native resolution of the Studiobook 16’s OLED display (3,840 x 2,400px), and on desktop, on a 32-inch 4K display running at its native resolution of 3,840 x 2,160px.

Benchmark results

Viewport performance

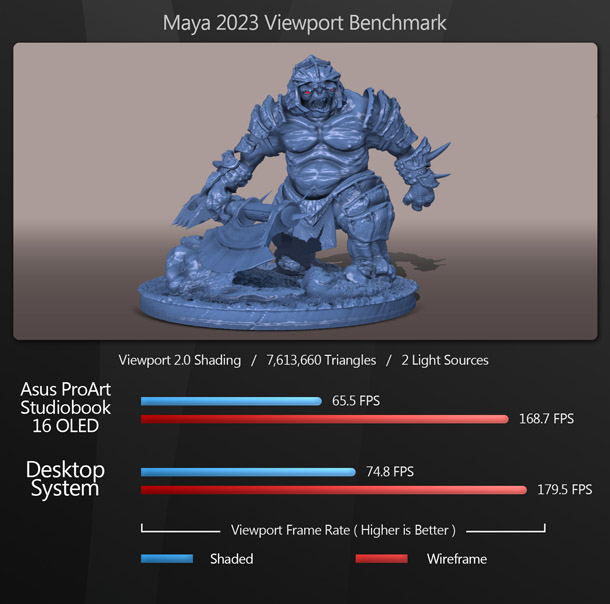

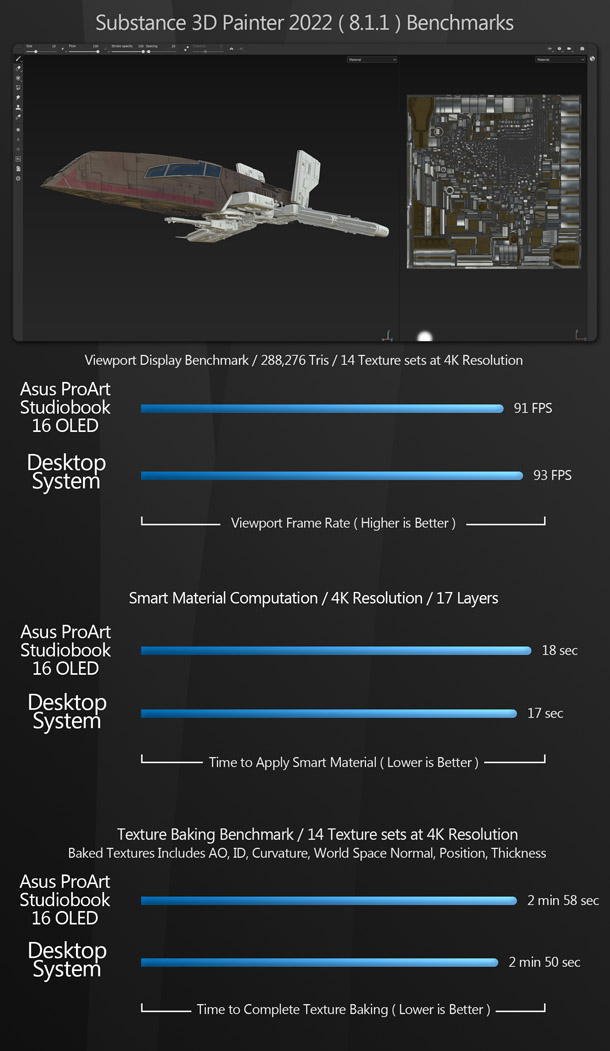

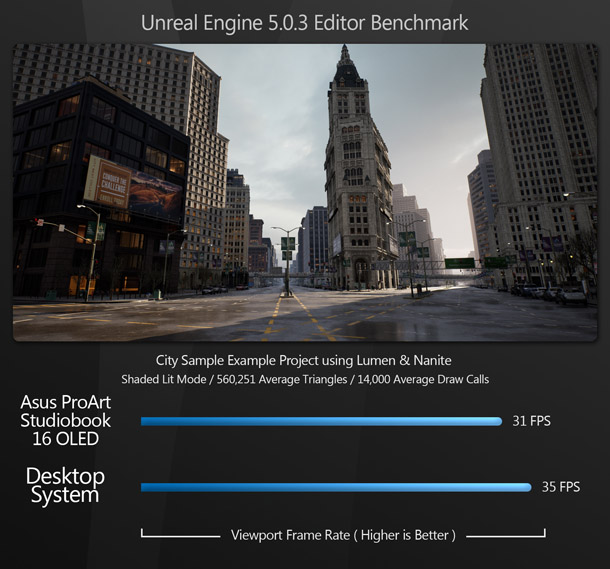

The viewport benchmarks include key DCC applications 3ds Max, Blender and Maya, plus 3D painting tool Substance 3D Painter, scene exploration tool Chaos Vantage, and game engine Unreal Engine.

In the viewport benchmarks, the desktop version of the GeForce RTX 3070 GPU in the Dell XPS beats its mobile counterpart in the Studiobook 16 by an average of around 5-10% – although that may be less about the performance of the hardware than the fact that the desktop card is driving a traditional 3,840 x 2,160px 4K display, whereas the mobile card has to push roughly 11% more pixels to drive the Studiobook’s 3,840 x 2,400px display. In any case, at these frame rates, the difference is barely noticeable.

Rendering

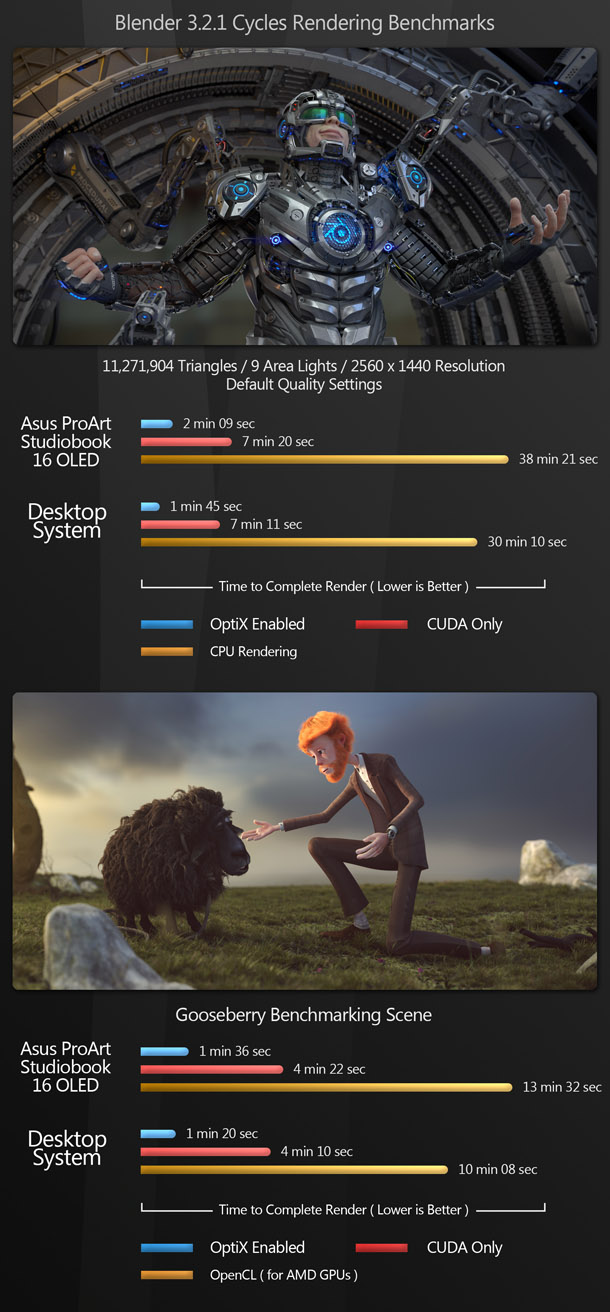

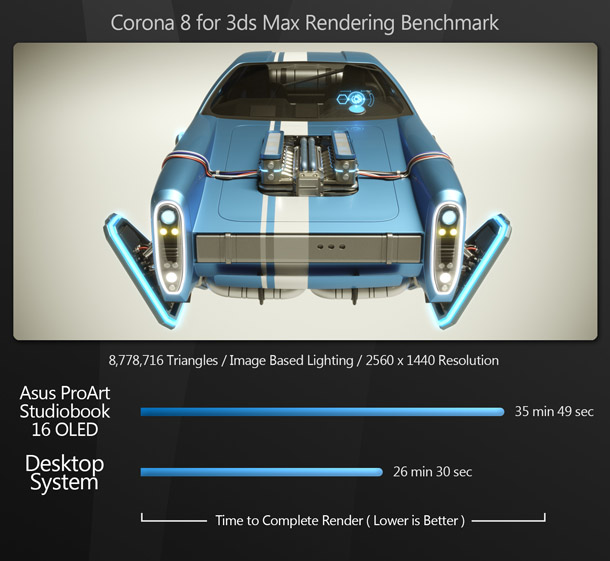

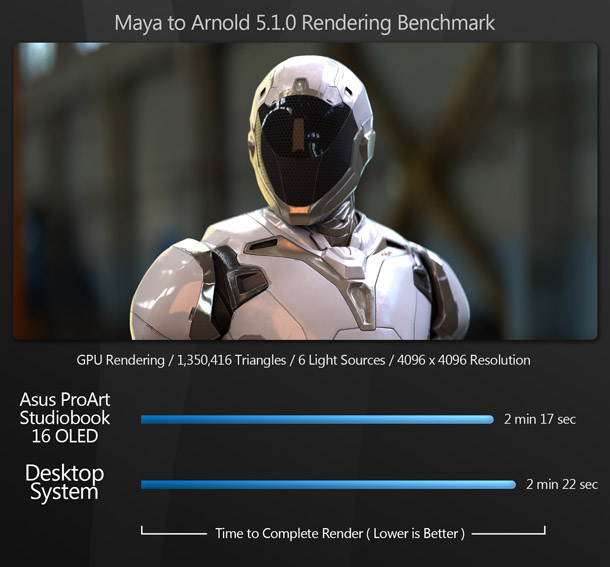

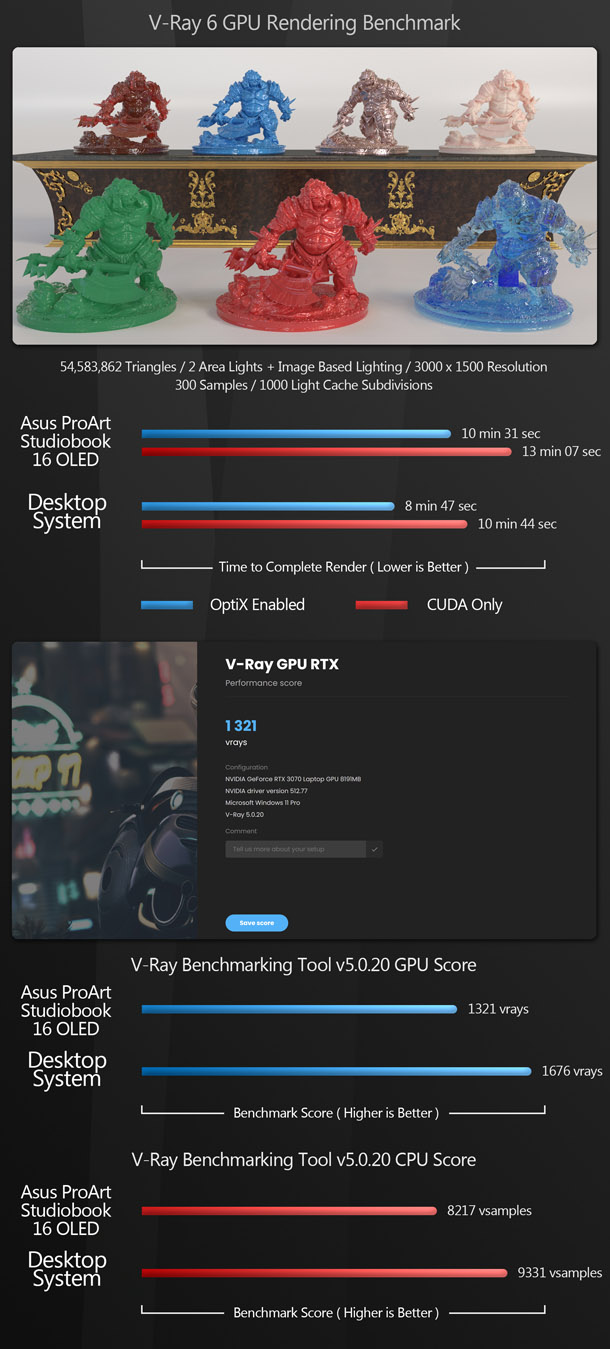

The rendering benchmarks include both CPU and GPU renderers. Corona runs on the CPU; Arnold and V-Ray were tested on the GPU; and Blender’s Cycles renderer on both.

The rendering benchmarks yield similar results to the viewport display tests, providing the GPU is being used for rendering. For the two CPU rendering benchmarks – Blender’s Cycles renderer and Corona – the performance gap increases, with the two extra CPU cores of the desktop system’s Core i9-10900K providing additional rendering horsepower compared to the Studiobook’s Ryzen 9 5900HX.

Other benchmarks

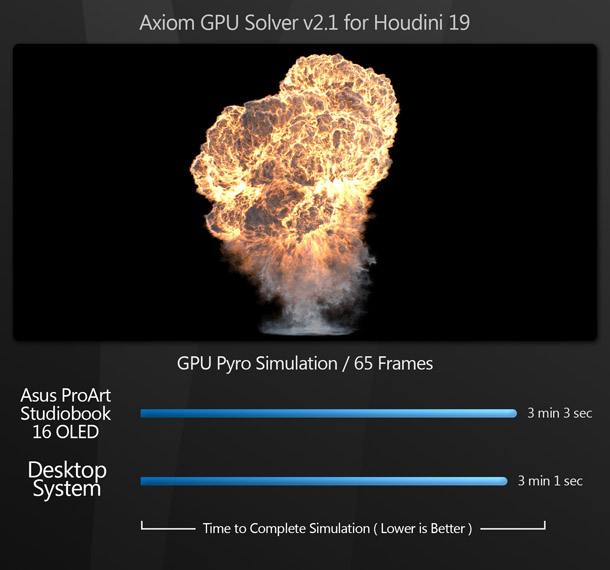

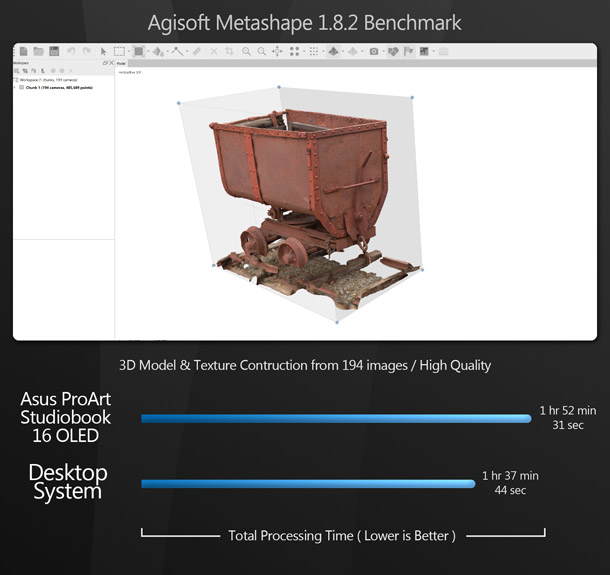

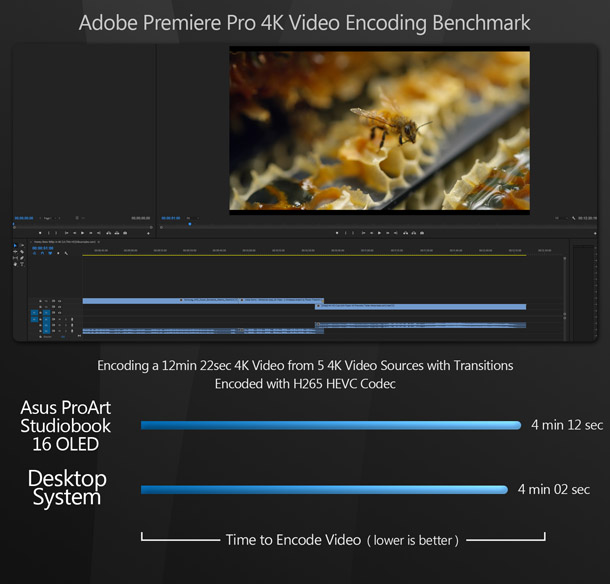

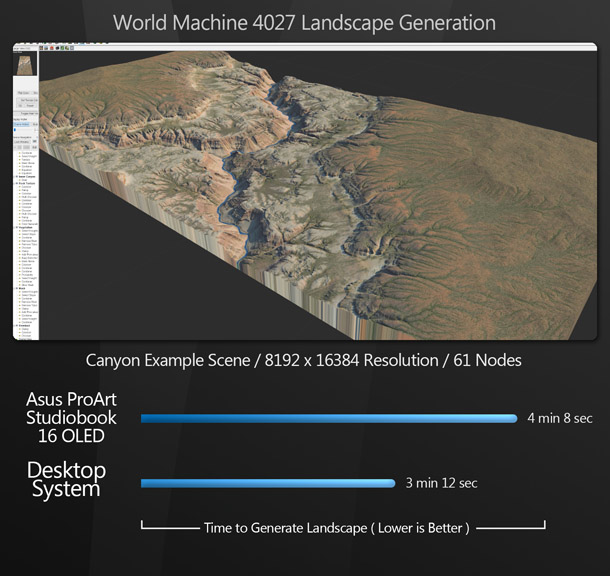

The next set of benchmarks covers more specialist apps: volumetric fluid solver Axiom, photogrammetry software Metashape, video editor Premiere Pro and terrain generator World Machine.

The additional benchmarks follow a similar pattern to the viewport and rendering tests, with the Studiobook 16 running neck-and-neck with the desktop system on the GPU-based Axiom solver, but the desktop system taking the lead in the other benchmarks, where the CPU comes into play.

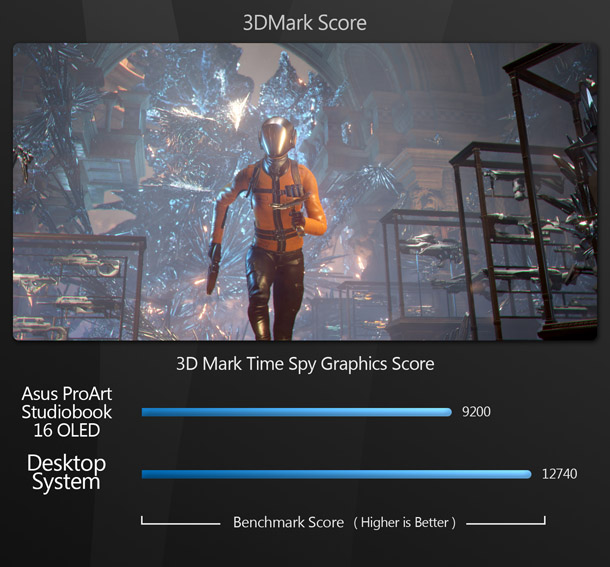

Synthetic benchmarks

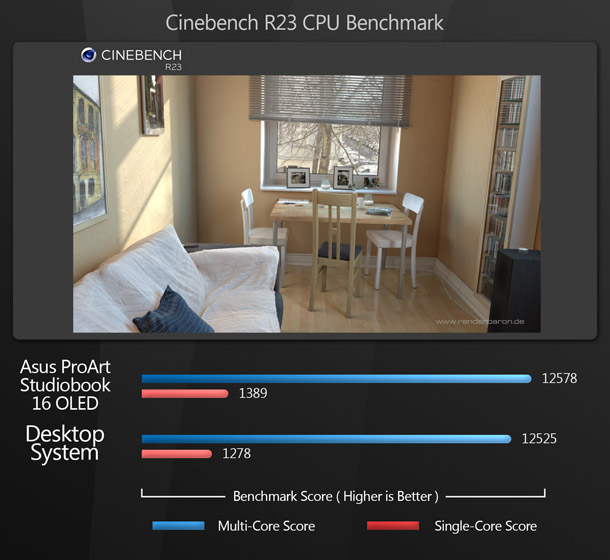

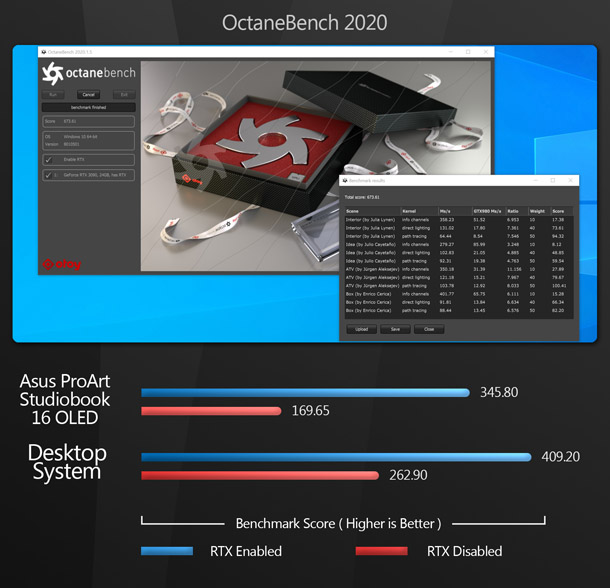

Finally, we have three synthetic benchmark tests. Synthetic benchmarks don’t accurately predict how a machine will perform in production, but I’ve include them here as a way to make approximate performance comparisons to other systems, since databases of scores are available online.

Our synthetic tests yield some interesting results. 3DMark and OctaneBench perform roughly as expected, with the desktop system taking the lead over the Studiobook, albeit not by much.

But with CPU benchmark Cinebench, the Studiobook actually beats the desktop system by a small margin, despite its disadvantage in both CPU core count and clock speed. I am not sure why this is, but my suspicion is that Cinebench just plays nicer with AMD’s Zen 3 CPU architecture, which is slightly newer than the Intel Comet Lake CPU in the desktop system.

Other considerations

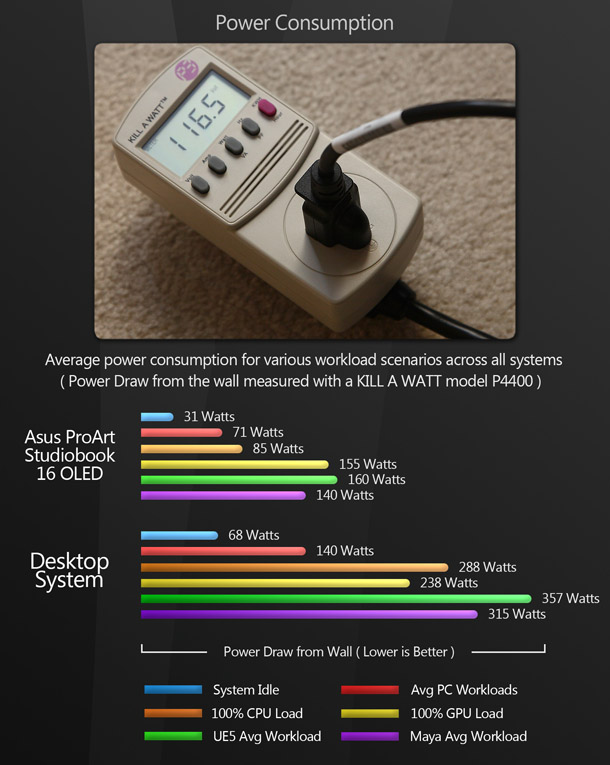

Power consumption

Given how similar the performance of the two systems is, you might expect them to use a similar amount of energy. In fact, the Studiobook 16 uses significantly less power than the desktop system: in some cases, less than half. This would explain why it doesn’t get uncomfortably hot under normal use. A few spots around the keyboard get quite warm with extended use, but I have used mobile systems that run much hotter.

Display quality

Finally, we come to the Studiobook 16’s big, bright, beautiful display. This was my first experience with an OLED PC display, and I loved it. Colors are bright and beautifully saturated, the blacks are really black, and the overall contrast is amazing.

My desk is cluttered with LCD and LED desktop displays, and in my opinion, it beats all of them easily – including a couple that are more expensive than the entire Studiobook 16. Even if the system itself were complete garbage (it isn’t – quite the reverse), the display alone would be a strong argument in its favour.

The Nvidia Studio platform

Before we get to the final verdict, I want to dive into the Nvidia Studio ecosystem that the ProArt Studiobook 16 is part of. Nvidia touts its Studio line of desktop and mobile systems as tools to allow artists to ‘create at the speed of imagination’. The Studio ecosystem has three components: hardware, drivers and software.

The hardware component is a set of standards that system vendors need to meet to receive the Nvidia Studio stamp of approval. There are specific requirements for the CPU, GPU, RAM, storage and display, but systems don’t need to include GPUs from Nvidia’s RTX Axxxx series of professional GPUs: most of those currently available via Nvidia’s e-store have consumer GeForce RTX GPUs. Professional cards still have their place for tasks that need very high graphics memory capacities, but for the majority of creative work, consumer GPUs are perfectly capable, and it seems that Nvidia is finally acknowledging this.

The next component of the Nvidia Studio ecosystem is GPU drivers. For a long time, only Nvidia’s professional GPUs (the RTX Axxxx series, and before it, the Quadro cards) got drivers specifically tuned for DCC applications, but the Nvidia Studio drivers now give consumer GPUs the same treatment.

The final component of the Nvidia Studio ecosystem is a set of software applications available to Nvidia Studio users (you can download them even if you don’t have a Nvidia Studio system, but they all require a Nvidia GPU): Nvidia Canvas, Nvidia Broadcast, Nvidia Omniverse and the Nvidia Texture Tools Exporter. I haven’t had a chance to do a deep dive into them, but these are my initial reactions.

Nvidia Canvas is an AI-based image-creation tool that enables you to paint simple brushstrokes on a blank canvas and have Canvas generate a photorealistic landscape based on them. It can generate quite impressive results under very specific conditions, but most of the time, the output isn’t of professional quality. For concept artists, it could be a quick way to generate a base image that can then be refined in Photoshop or other image-editing software, but it seems more like an AI showcase than a practical DCC tool, and is massively outclassed by AI-based image generators like Midjourney.

Nvidia Broadcast is a suite of AI-based audio and video filters that can be applied to the output of your system’s microphone and camera to enhance streaming and video conferencing. It can be used with most common platforms, including Discord, Zoom and Google Meet. This is the Studio application I really like. It doesn’t do anything revolutionary: just processes audio and video in the same way that most streaming platforms do natively, but much better! Since it’s free for anyone with a current Nvidia GPU, there’s no reason not to use it, although users with sub-$100 webcams and mics will see the most benefit.

Next is Nvidia Omniverse. Omniverse is an interesting beast. It is advertised as a scene-assembly hub that can connect to popular DCC applications, enabling users to build, animate and render DCC projects, collaborating with other artists in real time. Think of it as Nvidia’s answer to real-time graphics engines like Unreal Engine or Unity, with multi-user collaboration and live links to DCC applications thrown in.

From a technical perspective, Omniverse is impressive. Nvidia basically wrote its own real-time graphics engine, and added multi-user capabilities at a core level. But I have yet to encounter a professional game development or content creation studio using it. That may change in future, but DCC apps can already build, animate and render scenes, and have a loyal and entrenched user base, while studios have their own tried-and-tested methods of collaboration. Entertainment artists are a finicky bunch, and we fear change!

However, I must admit that I have not spent enough time with Omniverse to really judge its usefulness. I will spend more time with it in the future to get a better understanding of its intended purpose and benefits.

Finally, we have the Nvidia Texture Tools Exporter. It’s a handy little app that generates several types of real-time friendly texture maps from from a source image, and is available as a standalone application or as a Photoshop plugin. I use it quite a bit to generate normal maps from photographs in those few cases where I am not using Substance 3D materials or photoscanned textures, and it works quite well, especially since Photoshop’s native normal map conversion tool is, in my opinion, complete crap.

Verdict

It’s time to see if we can answer the big question that was asked early on in this article: is is better to use a desktop or mobile system for professional graphics work?

Let’s look at performance first. For the most part, the Asus ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED keeps up with a Dell desktop system with similar specifications. The desktop system comes out top in most of the benchmarks, but by a relatively small margin, and with the exception of a few CPU-heavy tests, you would hardly notice the difference in day-to-day work.

Next, price. As of the time of testing, I was unable to find any online shops selling Studiobook 16 systems with exactly the same configuration as our test machine. However, I did find a few with a GeForce RTX 3060 GPU instead of a RTX 3070, and those were selling for around $2,300, so I’d estimate a price tag of around $2,500. A Dell XPS system with similar specs to the desktop machine, but a newer 16-core Intel Core i9-12900 CPU, cost a little over $2,400. Given that with the desktop system, you would need to pay extra to upgrade to an OLED display, I’d say the Studiobook 16 actually wins on cost.

So what conclusions can we draw? First, that Nvidia Studio mobile workstations can indeed be used for demanding content creation tasks. And second, when it comes to cost, there is now little difference between similarly performing mobile and desktop systems.

Some of you may now be thinking: ‘If this mobile system is so great, why would I ever want to use a desktop system again?’ Well, despite the strengths of the ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED and other Nvidia Studio laptops, mobile systems do have two really big drawbacks.

The first is that a desktop system is easily upgradeable, whereas a mobile system is not. In most cases, you can only upgrade the memory and storage, and even those top out at much lower values than in a comparable desktop system.

The second is that while a mobile system may perform on par with an equivalent desktop machine, you can build desktop systems that are far more powerful than available mobile systems. Currently, mobile systems top out at 8-12 CPU cores, 32-64GB of RAM and 2-4TB of storage. With desktop systems, you can get up to 64 CPU cores, several terabytes of RAM, and storage arrays of over 40TB. Granted, these parts are very expensive, but you have the option to use them, whereas with a mobile system, you do not.

If you need your primary system to be portable, or you just prefer the form factor of a laptop, a Nvidia Studio mobile system will be a good fit. (And in the case of the Asus ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED, that beautiful OLED display is a real selling point.) If upgradeability is important to you, or you simply need more raw processing power – and can afford to pay for it – a desktop system will fit your needs better.

Finally, thank you for stopping by and taking the time to check out this review. My goal is to offer digital artists an in-depth look at modern hardware and software solutions, and how they really cope with DCC tasks. I hope that this has been an enjoyable and informative read, and to see you again at the next one!

Links

Read more about the ProArt Studiobook 16 OLED laptop on the Asus website

Read more about the Nvidia Studio ecosystem

About the reviewer

Jason Lewis is Environment Art Lead at Team Kaiju and CG Channel’s regular reviewer. You can see more of his work in his ArtStation gallery. Contact him at jason [at] cgchannel [dot] com

Acknowledgements

I would like to give special thanks to the following people for their assistance in bringing you this review:

Shannon Baker of Zeno

Daria Bianchini of Zeno

Stephen G Wells

Adam Hernandez

Thad Clevenger