Review: HP ZBook 17 G2 mobile workstation

It comes with a hefty price tag, but HP’s top-of-the-range mobile workstation is an uncompromising performer that can hold its own against any standard desktop system when it comes to DCC work, says Jason Lewis.

At the beginning of the year, we took a look at HP’s mid-range professional mobile workstation, the ZBook 15. Other than the entry-level GPU it came installed with, it proved to be quite a potent little performer. In this review, we’re going to take a look at how its big brother, the ZBook 17 G2, handles our real-world benchmarks, in addition to gauging its performance against a desktop system with comparable hardware.

Desktop or mobile?

Before we start, I want to address the question of desktop versus mobile systems. I’ve covered this in previous reviews, so if you’re a regular reader, you may want to skip ahead, but it’s an important topic for workstation buyers, and one worth addressing here. Can a mobile system like the ZBook 17 G2 really compete in performance with a desktop system? And more generally, is buying one a good idea?

Over the years, I have reviewed several mobile workstations for CG Channel, and have shown that a mobile system can indeed match the performance of a similarly specified desktop system, albeit at a higher price point. Desktops don’t really outstrip mobile workstations in performance until you get to six/eight-core or multi-CPU systems, or consumer desktop systems with ultra-high overclocking. These days, the real trade-offs to consider when buying a mobile system are ergonomics and upgradability.

The second question is more difficult to answer as it is totally dependent on your individual needs. The portability of a mobile system is a nice feature – or even a necessary one if you are a professional who often needs to work in the field. Alternatively, if you need to handle computationally intensive tasks, or you need expandability, a desktop system may be better suited to your needs.

System specifications and price

Unlike the mid-range ZBook 15, the ZBook 17 G2 is packed with high-end parts. Whereas the main bottleneck in the ZBook 15 was its entry-level graphics card, the ZBook 17 G2 comes with the most powerful of Nvidia’s current generation of mobile GPUs, the Quadro K5100M, which packs in 8GB of GDDR5 memory.

Our ZBook 17 G2 came equipped with a quad-core Intel Core i7-4940MX Extreme Edition mobile CPU with a base clock speed of 3.1GHz and the ability to scale up to 4.0GHz with lightly threaded applications using Intel’s Turbo Boost technology. The processor is Hyper-Threaded (four physical cores, eight threads), which boosts per-core performance roughly 10% over the previous Ivy Bridge architecture. Its Haswell architecture is built on a 22nm process, which helps keep power consumption and thermal performance in check.

The system also sported 16GB of DDR3-1600 RAM, which easily matches most desktop workstations. While the ZBook 17 G2 can support up to 32GB RAM, to do that, you would need to replace its four 4GB modules with 8GB modules, which would increase the cost significantly.

The ZBook 17 G2’s storage set-up is unique: the primary system drive is HP’s 256GB Z Turbo Drive – essentially an SSD that is plugged directly into a PCIe interface, thus bypassing the standard serial ATA hard drive controller and allowing for increased data throughput and deceased access times. I have no way to determine exactly how much faster it is than a standard SSD drive, but all operations that involve disk I/O – system boot-up, loading applications, copying files, and so on – were lightning quick.

In addition to the Z Turbo Drive, I installed an OCZ 256GB SSD drive to use as additional storage, as the Turbo Drive alone isn’t enough to hold all the data I use for benchmarking purposes.

As equipped, the system comes in at a little over $6,000 in HP’s online store. Unlike the ZBook 15, I was unable to find any third-party retailers selling the same configuration cheaper. At time of writing, Newegg.com was selling a system for $3,765, but with a slower CPU, Quadro K4100M GPU, a standard 256GB SSD in place of a Z Turbo Drive, and a standard 24-bit display.

First impressions

The display

The immediate stand-out feature of this system is its display. While the dimensions and resolution are relatively standard (17”, full HD), it’s one of HP’s 30-bit DreamColor displays, meaning that it can display over a billion colours, as opposed to the 16.77 million possible on a normal 24-bit display.

There is some argument as to how many colours the human eye can distinguish: some sources say 10 milllion; others claim the figure is higher. The biggest difference that most people notice with a 30-bit display is in imagery with smooth gradients of hue or tone: a 30-bit display offers 1,024 levels per channel, as opposed to the 255 provided by a 24-bit display.

Currently, 30-bit displays are a niche market: the only DCC professionals who really need them are high-end photographers, compositors and colourists, who need to work with broad colour ranges, such as the full Adobe RGB gamut. However, regardless of whether you need 30-bit colour, the overall quality of the display is superb. Colours are bright and vivid, blacks are deep and inky, and unlike the IPS display in the ZBook 15, there is almost no colour or brightness shift when viewing the panel off-centre until you get to fairly extreme angles.

The only real gripe I have (and it’s one that applies to all mobile full HD displays) is that it’s still only television HD resolution: 1,920 x 1,080 pixels. The norm these days in the DCC industry for desktop workstations is 1,920 x 1,200. Those 120 extra pixels may not seem like a lot, but they make a big difference when working with DCC applications that use a lot of toolbars or panels: 120 lines of vertical resolution is enough for an entire extra toolbar or shelf. UHD displays, which offer a resolution of 3,840 x 2,160, are just starting to show up in mobile systems, and will be a welcome change.

Build quality and keyboard

Like all of HP’s professional systems, the build quality of the ZBook 17 G2 is outstanding. The system is simple, yet elegantly designed, and overall, it feels very solid and sturdy. It makes use of lots of nice metallic surfaces, and the parts that are plastic still feel high-quality.

The keyboard is also very solid, with the keys themselves offering a bit of, for lack of a better word, ‘clicky’ tactile feedback, making them feel more like those of a desktop keyboard. And like the ZBook 15, the ZBook 17 G2’s keys are backlit: a significant bonus if you, like me, do a lot of your work in the evenings or in low-light situations.

The trackpad on the ZBook 17 G2 is quite large and located in such a position that it is easy to access yet doesn’t get in the way while typing. In most cases, it’s a viable replacement for the mouse, as it allows for convenient and precise control of the cursor.

Size and weight

The external dimensions for the ZBook 17 G2 are pretty standard for a 17-inch mobile workstation: 16.37 x 10.7 x 1.33in (416 x 272 x 34mm) when the display is closed. It isn’t super-compact, like tablets, Ultrabooks, or many MacBooks, but given its significantly higher performance, the extra size is to be expected in order to accommodate and cool the higher-end components.

At 7.67lbs (3.46kg), the ZBook 17 G2 is also noticeably heavier than a consumer laptop. With a good case with a shoulder strap, I was able to take it with me on the move quite easily, although I did notice that if I had to carry it for longer than my typical commute to work, my shoulder would start to get fatigued.

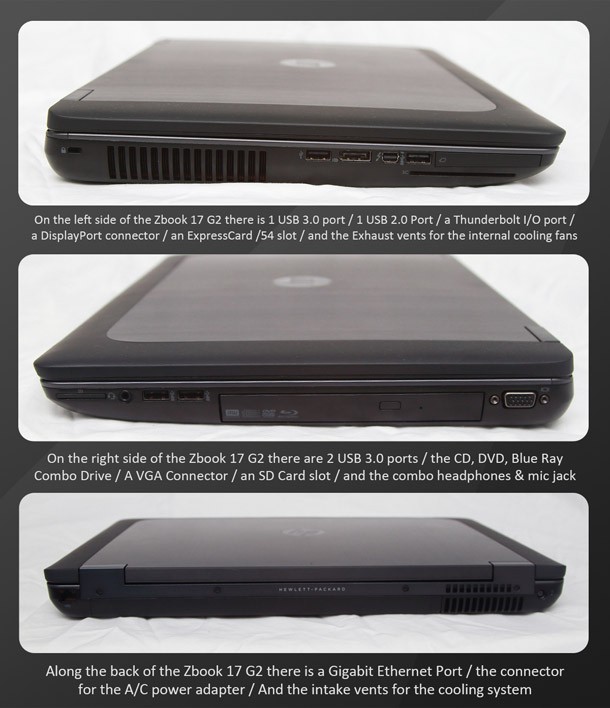

Connectivity

Like the ZBook 15, the ZBook 17 G2’s external connectivity is pretty standard among mobile workstations. Down the right side of the chassis there are a VGA graphics port, a combo CD/DVD/Blu-ray drive, two USB 3.0 ports, a combo line-in mic and stereo out headphone jack, and an SD card reader.

Down the left side of the chassis, there are a single USB 2.0 port, a DisplayPort video out connector, a single USB 3.0 port, an ExpressCard 54 slot, and a Thunderbolt 2 port: an especially nice addition, as Thunderbolt is becoming the preferred choice for those who require high-speed external devices such as fast storage or high-capacity disk arrays. Thunderbolt can also be used to drive external displays.

Along the back of the chassis are the connector for the external AC power adaptor and a single Gigabit Ethernet port for those who need a wired network connection.

As with the ZBook 15, one minor gripe is that it would have been nice to have an HDMI video out so that the system could be plugged into a flat-panel television for presentations that call for a large screen. A DisplayPort to HDMI converter doesn’t cost much, but it is another peripheral to carry with you.

Testing procedure

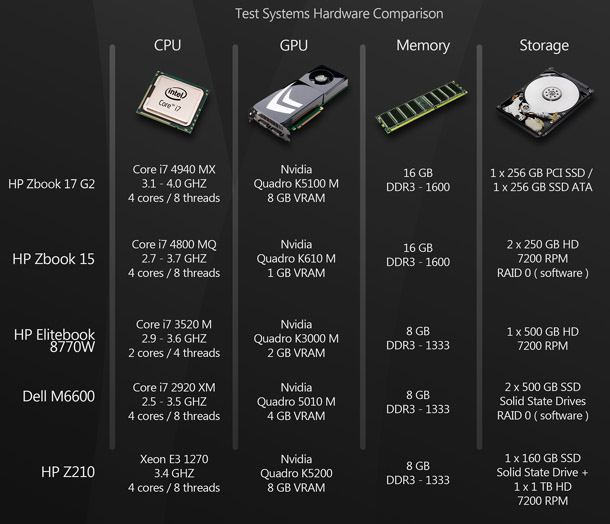

For this review we will be comparing the ZBook 17 G2’s performance against the ZBook 15 and the two other mobile systems I tested at the time: the Dell Precision M6600 and, where possible, the HP EliteBook 8770w. (I’m no longer in possession of the 8770w, so I wasn’t able to run some of the newer benchmark tests.) To assess how mobile workstations stack up against desktop systems, we will also include HP’s Z210 desktop.

It’s important to remember that that the benchmark scores are not intended to be a direct comparison between systems. The EliteBook is now two years old, the Precision M6600 is three years old, and the Z210 is older still, although since our original review, it has been fitted with a more recent Nvida Quadro K5200 GPU. They are included to show how mobile technology has progressed recently, and provide context for the ZBook 17 G2’s performance on common production tasks.

Below, you can find a chart summarising the specifications of the ZBook 17 G2 and the four other systems to which we will be comparing it.

Our benchmarking procedure consisted of running a collection of digital assets similar to those you would find in a real production environment through typical tasks in the following software:

DCC packages

3ds Max 2015, Maya 2015, Softimage 2015, Mudbox 2015, ZBrush 4R5, Modo 801, Mari 2.5, Fusion 6.4 LE

Simulation tools

Maya 2015 (cloth dynamics), RealFlow 2013

CPU-based renderers

mental ray 3.11, V-Ray 3.0, Maxwell Render 3.0, Arnold 1.1, RenderMan 20, Corona Renderer 1.0

GPU-based renders

Iray 3.1, Arion 2.7

Games engines

Unreal Engine 4.8.3, CryEngine 3.6.12

Other tools

xNormal 3.19.2, World Machine 2.3

Synthetic benchmarks

x264 HD 5.0.1, Cinebench 15

Each benchmark test was performed five to ten times, spread across four to seven testing sessions, with the figure quoted being the mean of the highest and lowest values observed.

All benchmarks were performed at a resolution of 1,920 x 1,080, except on the desktop Z210 system, which was run at a resolution of 1,920 x 1,200.

Benchmark results

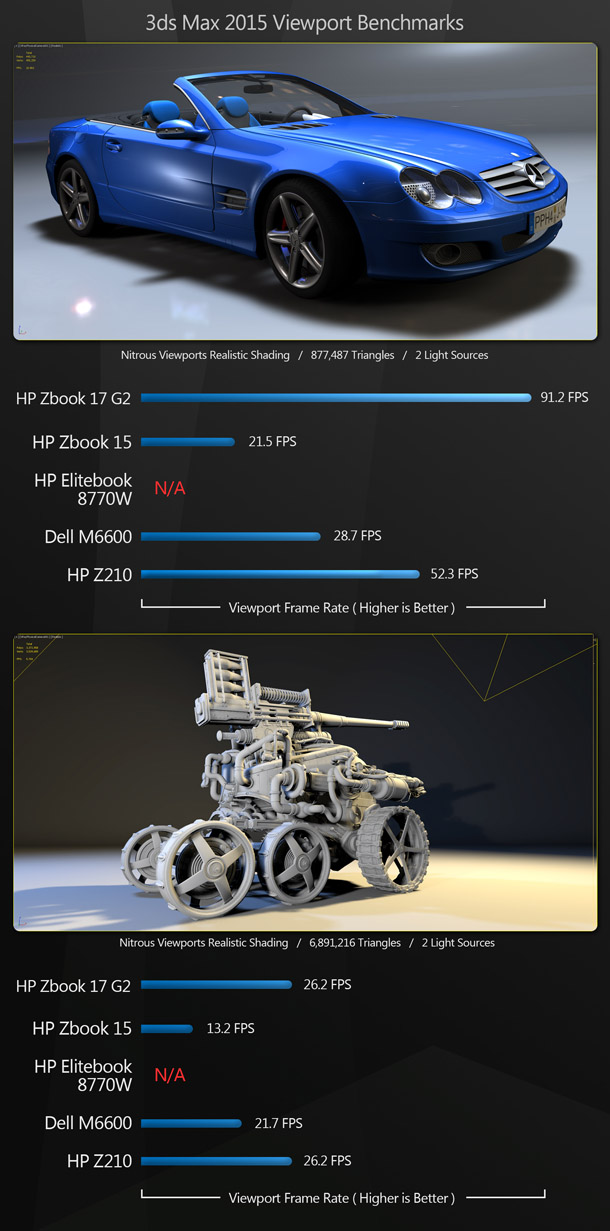

3ds Max 2015

First up, we have Autodesk’s 3ds Max modelling, rendering and animation software: one of the ‘big two’ in the industry – according to Autodesk reps, it and Maya make up 80% of the market for general-purpose DCC apps. The following benchmarks show average viewport frame rates for rotating, panning, vertex and face editing each model displayed. All were performed with the Nitrous viewport′s Realistic shading mode.

With the first benchmark, the ZBook 17 G2, with its Quadro K5100M GPU, takes a lead over the previous mobile systems, and even beats out the desktop system with its Quadro K5200 by a significant margin.

With the steampunk tank, it also beats out the previous mobile systems, but ties with the desktop Z210.

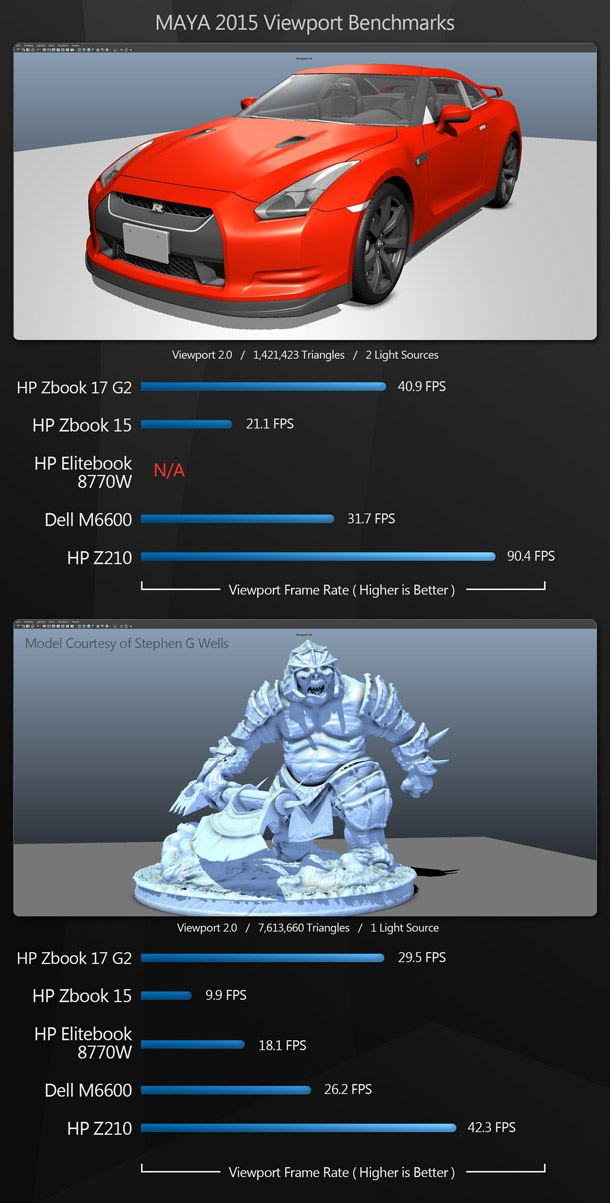

Maya 2015

Next we have the second of the ‘big two’ general-purpose DCC packages. Again, the benchmarks show average viewport frame rates for rotating, panning, vertex and face editing each model displayed. All were performed with Maya’s Viewport 2.0 shading mode.

With our Maya viewport tests, the ZBook 17 G2 again beats out all the previous mobile systems, but this time loses out to the desktop Z210 and its Quadro K5200.

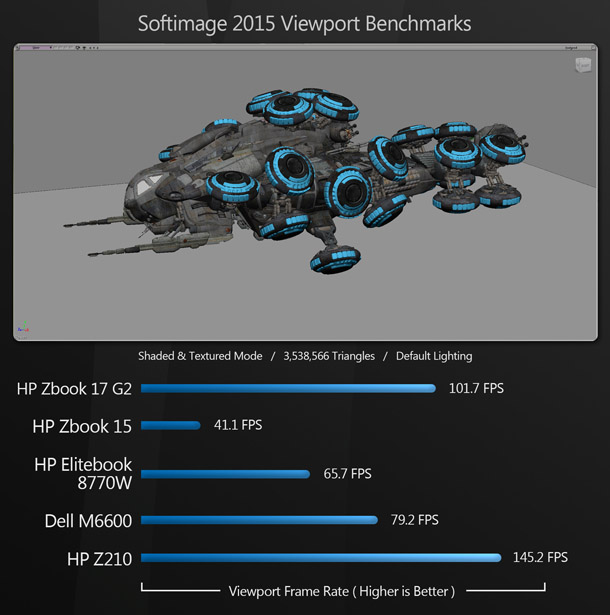

Softimage 2015

Softimage is the third general-purpose DCC application in Autodesk′s line-up. It is a full-featured 3D modelling, animation and rendering package.

Despite the fact that Autodesk has discontinued development of Softimage, and that the 2015 version is the last one, it still has a large user base and I will continue to include it in our benchmarks for the foreseeable future.

Again, it consists of averaged viewport frame rates for rotating, panning, vertex and face editing the test scene.

With Softimage, we see similar results to the Maya tests, with the ZBook 17 G2 beating out all the other mobile systems by a large margin, but coming in second to the desktop Z210 system.

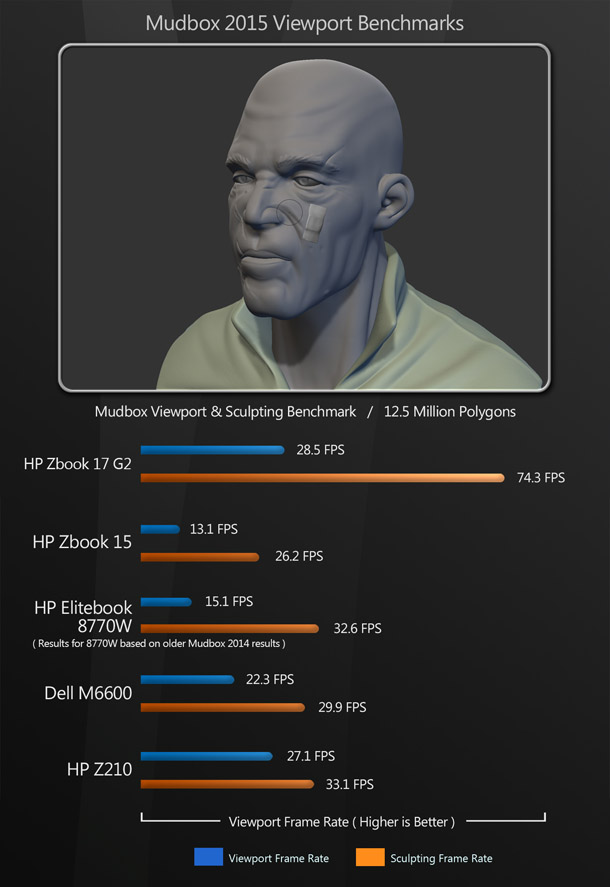

Mudbox 2015

The last piece of Autodesk software used for our benchmarks is the specialist digital sculpting package Mudbox. Digital sculpting applications tend to display assets with much higher polygon counts than their traditional DCC cousins. The benchmark tests both viewport and sculpting performance.

With Mudbox we see the ZBook 17 G2 take the top spot, just edging out the desktop Z210.

ZBrush 4R5

Like Mudbox, Pixologic’s ZBrush is a digital sculpting application. Unlike Mudbox, it uses the system’s CPU for all computational tasks, including viewport display.

Since ZBrush uses proprietary technology rather than traditional 3D APIs like OpenGL or Direct3D, there is no way – at least, none that I am aware of – to measure frame rates: software like FRAPS will not work, and ZBrush has no internal frame-rate counter.

Subjectively, however, performance was quite similar across all of the test systems. The ZBook 17 G2’s quad-core CPU and 16GB RAM are plenty to run ZBrush well.

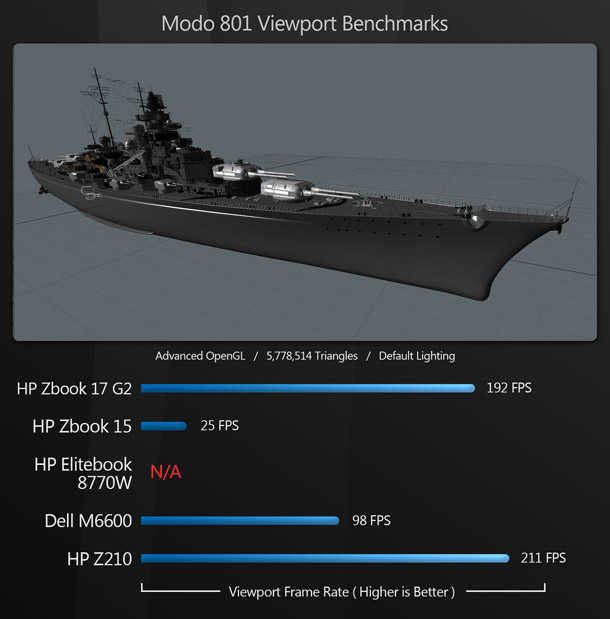

Modo 801

Next we have Modo, The Foundry’s 3D modelling, animation and rendering software. As with the Autodesk DCC applications, the Modo benchmark consists of averaged viewport frame rates for rotating, panning, vertex and face editing the scene shown.

Once again, the desktop Z210 system takes first place, followed closely by the ZBook 17 G2. The rest of the mobile systems trail the ZBook 17 G2 by a significant margin.

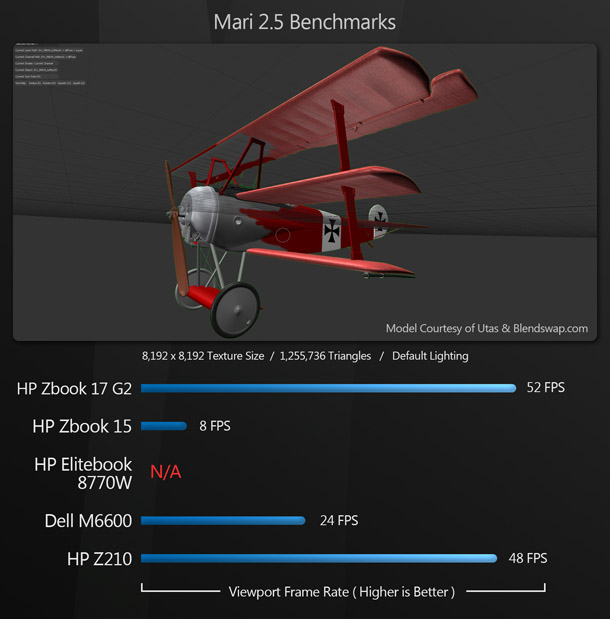

Mari 2.5

Our next display performance benchmark uses Mari, The Foundry’s 3D painting application. The Fokker DR1 triplane model is just over 600,000 polygons and the textures are 8,192 x 8,192 resolution.

With Mari, our ZBook 17 G2 takes the lead followed closely by the desktop Z210. The other mobile systems trail by a large margin.

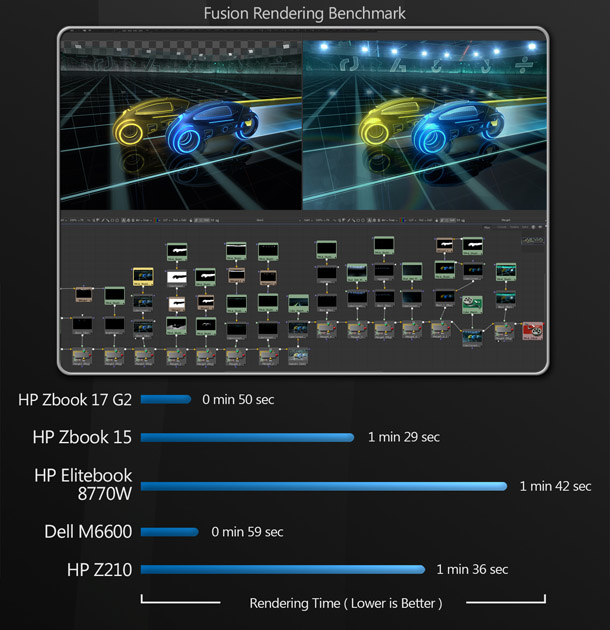

Fusion 6.4 LE

Fusion, recently acquired by Blackmagic Design, is a node-based compositing application. For this benchmark, we have a moderately complex composition consisting of multiple frame composites, colour correction passes, and frame distortions. The composition is 141 frames long, and is rendered at HD 720 resolution.

With our Fusion test, the ZBook 17 G2 takes first place once again, but it is interesting to note that the older Precision M6600 comes in just a tick behind. Although the ZBook 17 G2 has more powerful hardware, the M6600 has a pair of SSD drives in a RAID 0 configuration, and I’d speculate that this is responsible for its good performance here. The systems with mechanical hard drives fall behind those with SSDs.

Note that I didn’t test Fusion reading and writing from/to the ZBook 17 G2’s Z Turbo Drive. This might have pushed its performance even further ahead of the M6600, but there just wasn’t space on the drive to store all of the renderered frames generated by this benchmark test.

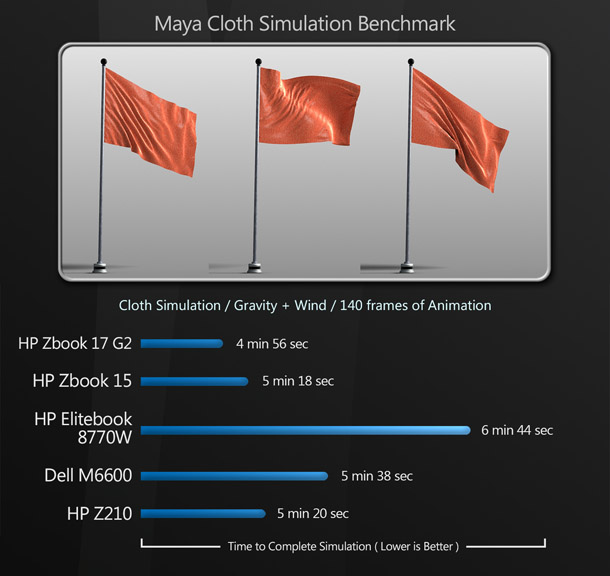

Maya 2015: cloth dynamics

Next, we have the first of our simulation tests, using Maya’s nCloth dynamics system. The test scene is a basic flag with gravity and wind force applied to it, simulated over 140 frames of animation.

Once again, the ZBook 17 G2 takes first place, this time followed by the ZBook 15, then the desktop Z210, the Precision M6600, and lastly the EliteBook 8770w.

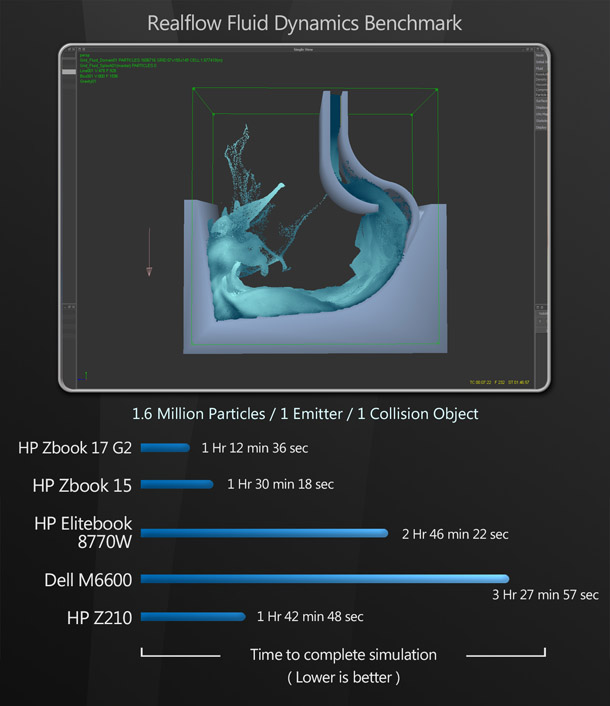

RealFlow 2013

Our second simulation test uses Next Limit’s fluid simulation software, RealFlow. RealFlow also has a grid-based solver, but we used the particle solver here, with the benchmark consisting of a 700-frame simulation with one emitter and one collision object. The particle count tops out at 1.6 million.

The results of the RealFlow test are similar to the cloth simulation: the ZBook 17 G2 takes first place, then the ZBook 15, then the Z210. The order of the final two systems is reversed, with the EliteBook 8770w in fourth and Precision M6600 in last place.

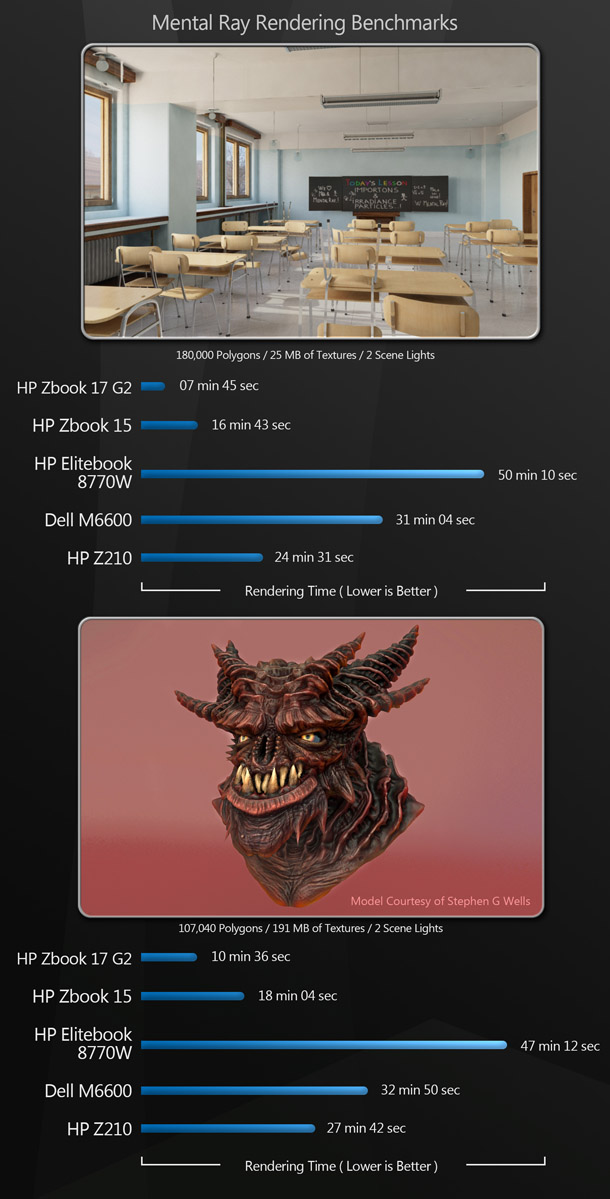

mental ray 3.11

Our first rendering benchmark uses Nvidia’s mental ray renderer. Together with Pixar’s RenderMan and Solid Angle’s Arnold, it is one of the more popular rendering packages for VFX and animation. It is largely CPU-based.

With our first rendering benchmark, the ZBook 17 G2’s Intel Core i7-4940MX CPU really flexes its muscles, taking a significant lead over the ZBook 15 – which, at the time of its review, did well in the CPU benchmarks.

After the ZBook 15, we have the desktop Z210, the Precision M6600, and lastly the EliteBook 8770.

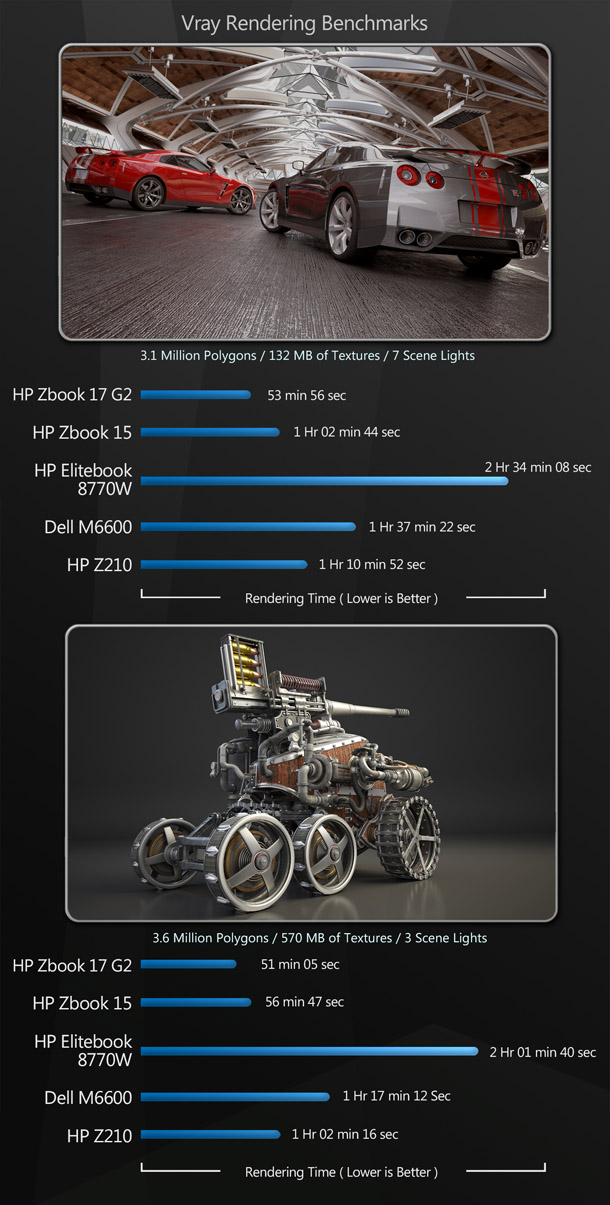

V-Ray 3.0

Chaos Group’s V-Ray is a third-party renderer for a range of DCC applications, including 3ds Max and Maya. It originally staked out a niche in visualisation, but has recently begun to gain traction in VFX work. Although V-Ray has a GPU-based interactive preview, we are using the CPU-based production renderer here.

The pattern of the V-Ray scores is similar to those for mental ray, although the ZBook 17 G2’s lead isn’t as wide.

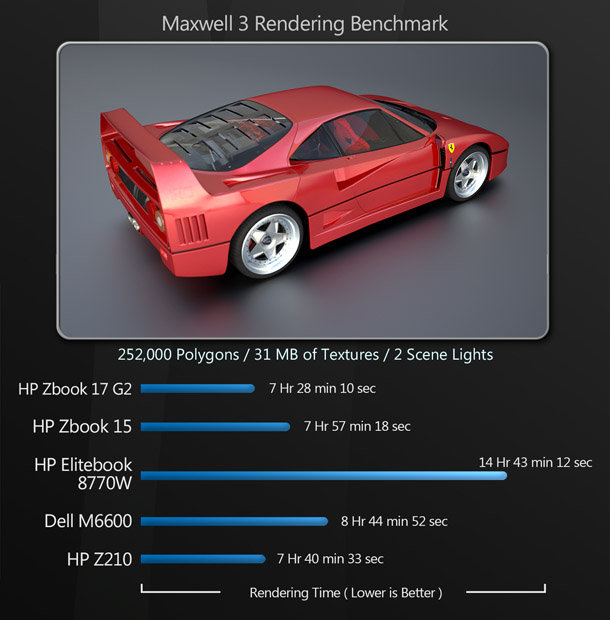

Maxwell Render 3.0

Next, we have Next Limit’s Maxwell Render: one of the first commercially available unbiased renderers.

Unbiased renderers have the advantage of a much simplified user experience and realistic output, but are usually significantly slower than their biased counterparts. Again, the production renderer is CPU-based.

The scores follow a similar pattern to mental ray and V-Ray, with the ZBook 17 G2 taking the lead, but here, it is followed by the desktop Z210, then the ZBook 15, the Precision M6600, and lastly the EliteBook 8770.

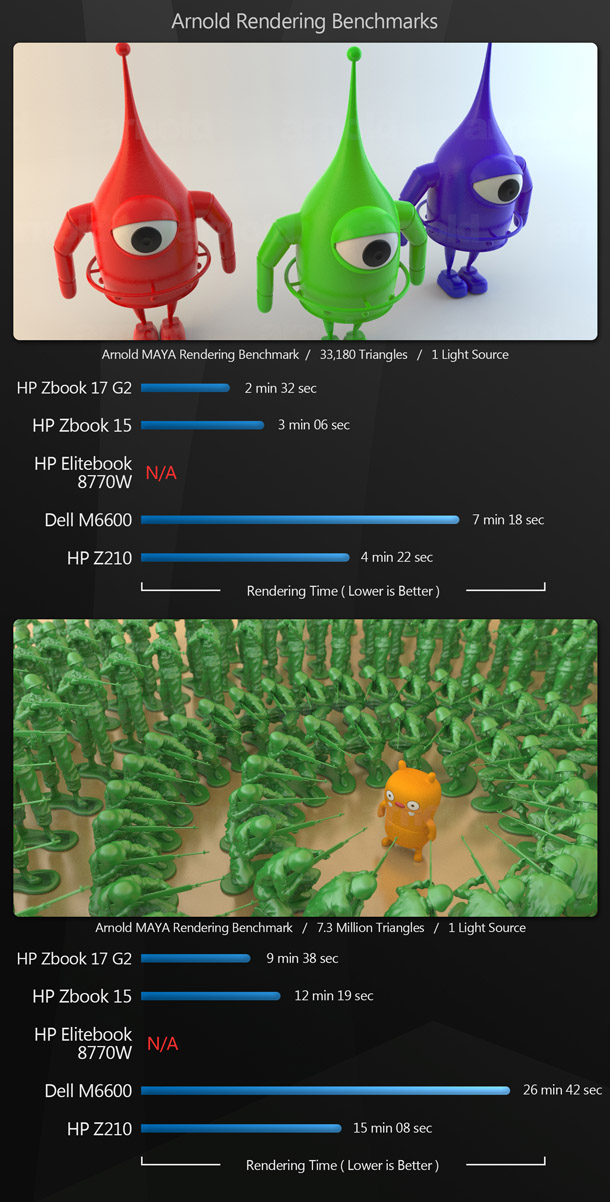

Arnold 1.1

Our newest render benchmarks include Solid Angle’s Arnold. Co-developed with Sony Pictures Imageworks, it is now offered commercially with plugins for Maya, Softimage, and Houdini. Again, it’s CPU-based.

With the Arnold benchmarks, the ZBook 17 G2 once again takes the top spot, followed by the ZBook 15, the desktop Z210, and lastly, the Precision M6600.

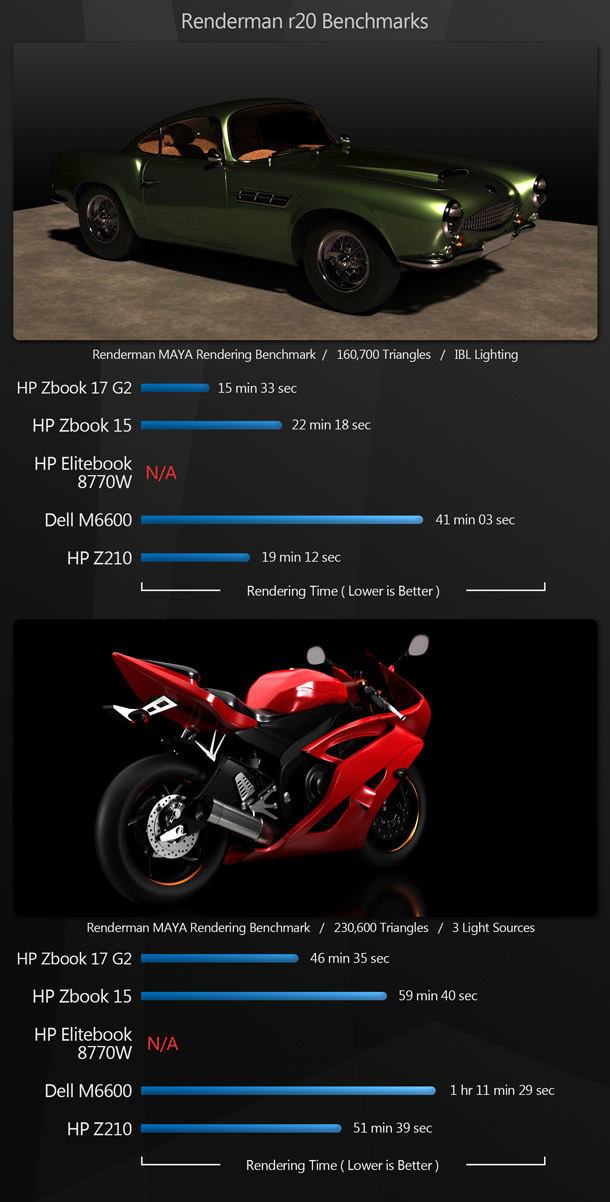

RenderMan 20

RenderMan is Pixar’s production renderer, initially based primarily on the REYES algorithm, and more recently, introducing a new raytracing architecture. Dominant in VFX and animation for decades, its market share has recently been eroded by newer renderers like Arnold. Once again, it’s CPU-based.

The RenderMan benchmarks follow the same pattern as Arnold: the ZBook 17 G2 takes first place, followed by the desktop Z210, the ZBook 15, and lastly the Precision M6600

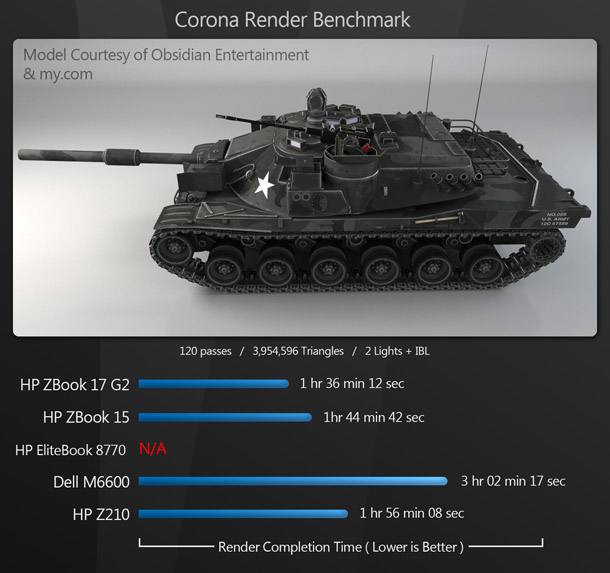

Corona Renderer 1.0

Render Legion’s Corona is a relatively new unbiased path tracer, currently integrated into 3ds Max. Like Maxwell, it’s a progressive renderer, and offers incredibly photorealistic results with minimal finagling. Also like Maxwell, it’s CPU-based.

With Corona the ZBook 17 G2 again takes the top spot, this time followed by the ZBook 15, the desktop Z210, and the Precision M6600.

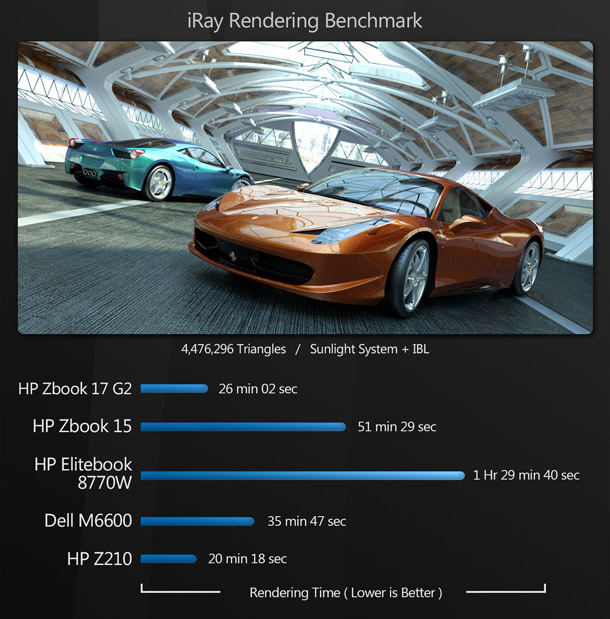

Iray 3.1

Our first GPU rendering benchmark uses Iray. Developed by Nvidia, Iray is a hybrid CGU/GPU renderer that comes integrated into 3ds Max, and can be enabled with Maya, albeit with some finagling.

The Quadro K5200 in the desktop Z210 system excels at GPU computing tasks, and takes top spot here. The ZBook 17 G2 comes in next, followed by the Precision M6600, the ZBook 15 and the EliteBook 9770w.

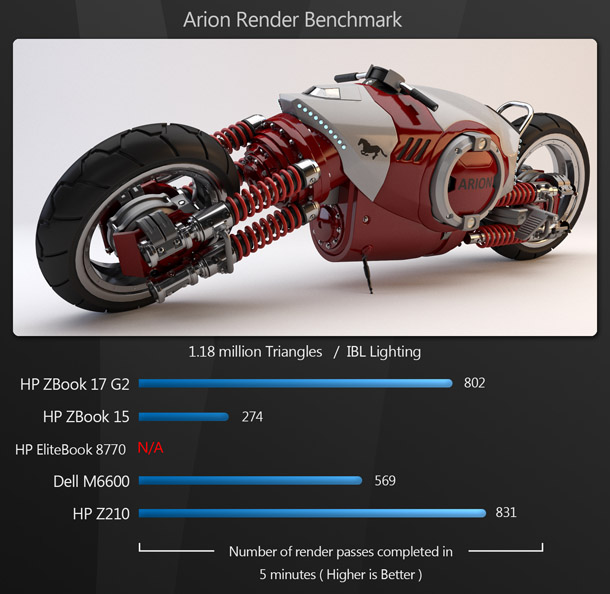

Arion 2.7

RandomControl’s Arion is a standalone renderer with plugins for most DCC applications. Like Iray, it is a hybrid CPU/GPU renderer. The Arion benchmark is a little different in that instead of measuring the time to render a single frame, I set a five-minute time limit and recorded the number of render passes completed in that time.

With Arion we see similar results to Iray, with the desktop Z210 coming in first, followed by the ZBook 17 G2, the Precision M6600, and lastly the ZBook 15.

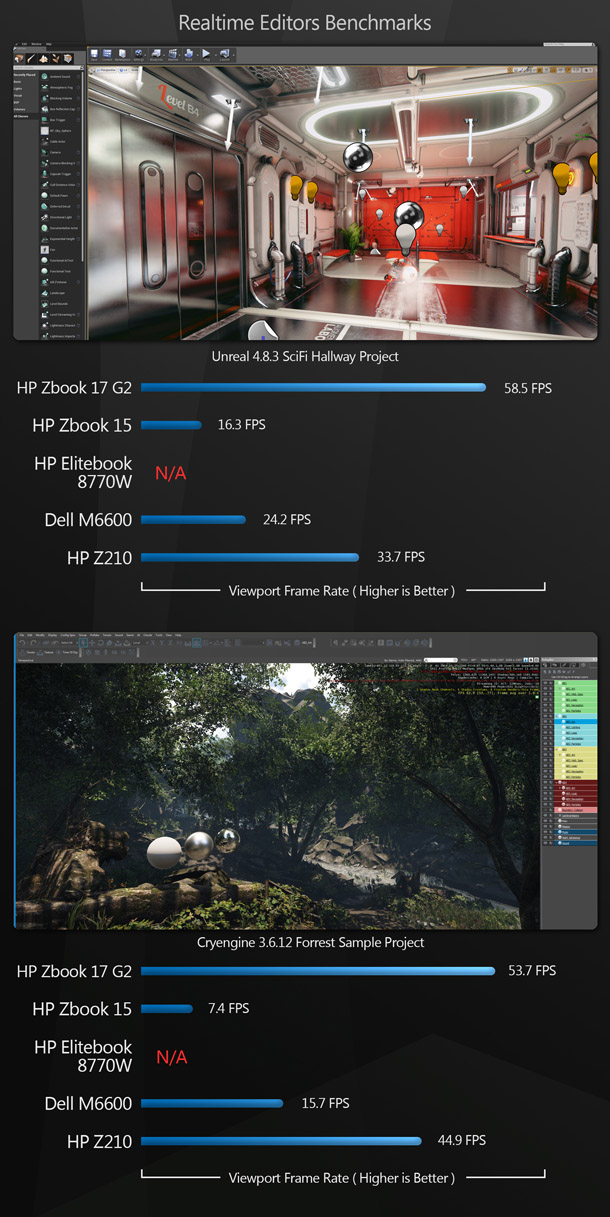

Unreal Editor 4.8.3 and CryEngine Editor 3.6.12

In addition to standard DCC software, many game developers use the dedicated editors provided with game engines in their work. Two of the most widely used are Epic Games’ Unreal Engine and Crytek’s CryEngine. Both benchmarks run in the editor at the same resolution as our systems’ desktops.

With our real-time editors, the ZBook 17 G2 takes the lead again, this time by a fairly large margin. The desktop Z210 comes in second, and then the remaining mobile systems follow some way behind it.

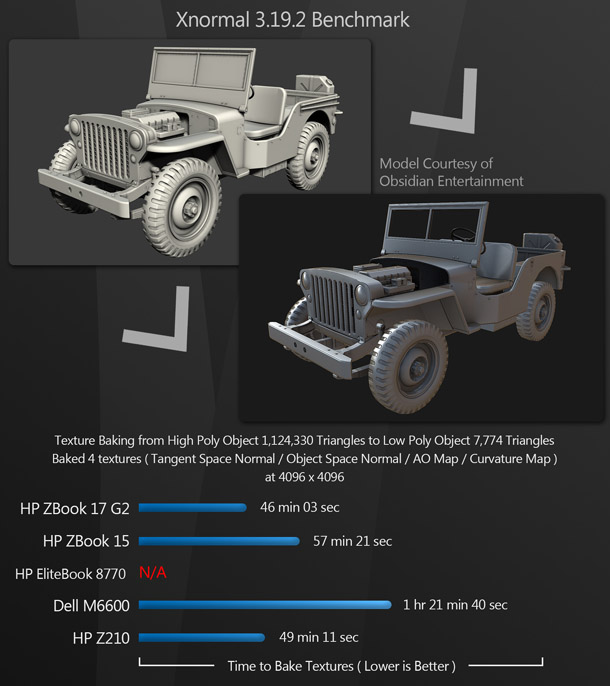

xNormal 3.19.2

Our next benchmark is the independently developed freeware tool xNormal, which generates common games maps based on the topology of a mesh. It is fully multi-threaded and also uses the GPU to render the maps.

With xNormal, the ZBook 17 G2 takes first place, followed closely by the desktop Z210, then the ZBook 15, and lastly, the Precision M6600.

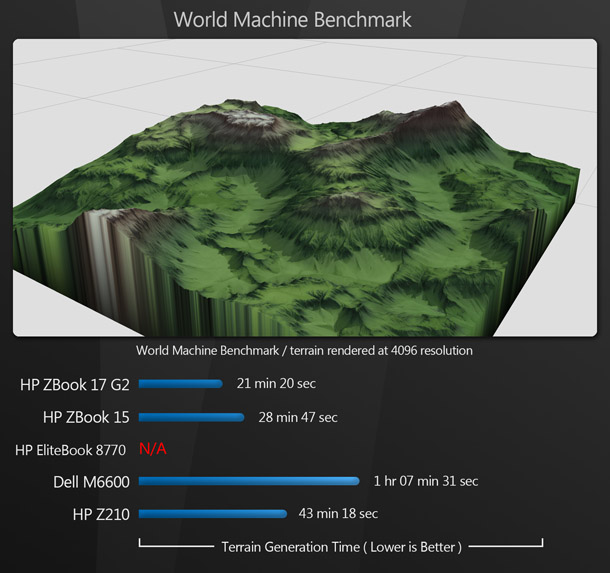

World Machine 2.3

World Machine Software’s World Machine is a procedural terrain generation tool that has become increasingly popular in recent years, both in games and visual effects.

With World Machine, the ZBook 17 G2 again takes first pace, with the ZBook 15 coming in second, followed by the desktop Z210, and lastly the Precision M6600.

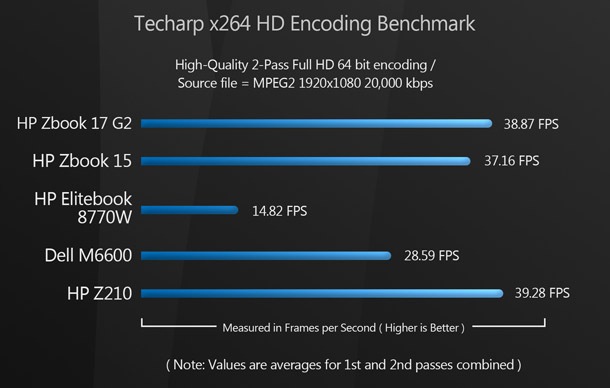

x264 HD 5.0.1

Tech ARP’s x264 HD benchmark tests performance encoding a 1080p video clip into a high-quality multi-pass x264 video file. The benchmark is multi-threaded and runs in 64-bit. Results are given in frames per second. You can download the benchmark here.

This time, the desktop Z210 takes the lead, with the ZBook 17 G2 coming in a close second, and the ZBook 15 not far behind it. They are followed by the Precision M6600, and lastly the EliteBook 8770.

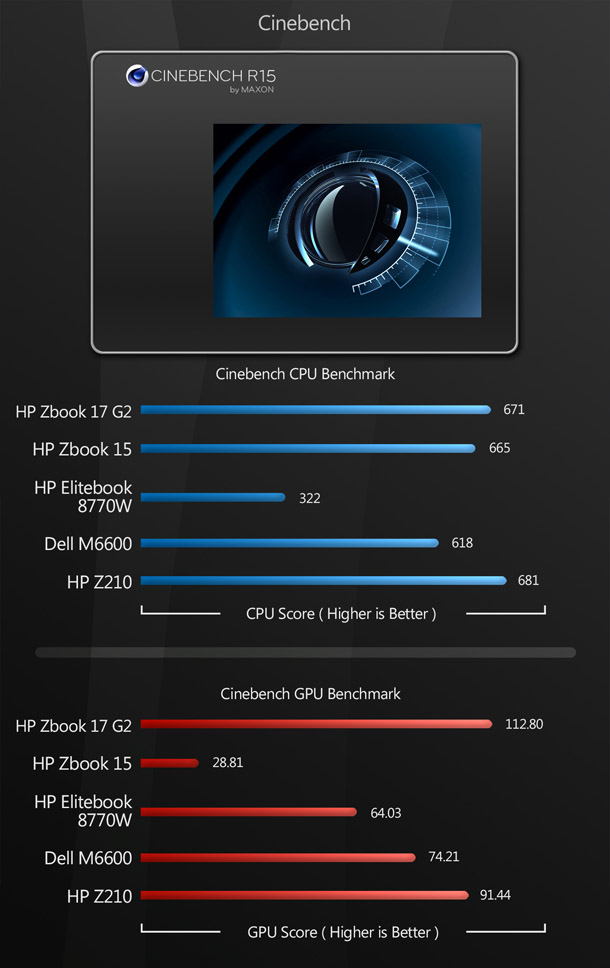

Cinebench R15

Those of you who are familiar with my previous reviews will know that I am not a fan of the synthetic benchmarks that so many other reviewers rely on. This is simply due to the fact that the results they generate do not reflect the performance you would find in real production situations. Despite this, I have had requests from readers to include Cinebench results, so it is the one synthetic benchmark I include. You can download it here.

There are two results: a CPU score and a GPU score. In the CPU benchmark, the Z210 comes in first with the ZBook 17 G2 taking second, the ZBook 15 third, the Precision M6600 fourth, and the EliteBook 8770 last.

With the GPU benchmark, the ZBook 17 G2 takes first place, followed closely by the Z210. The Precision M6600 comes in third, the EliteBook 8770 fourth, and the ZBook 15 comes in last.

Other considerations

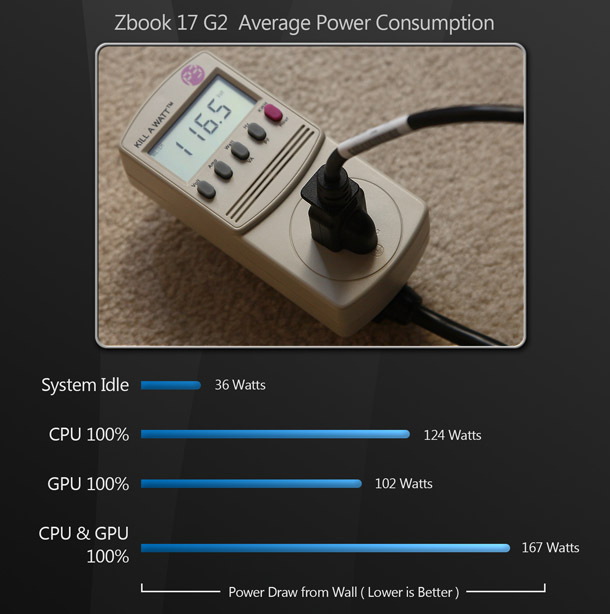

Power consumption

Next, let’s take a look at a few of the other characteristics that are critical for mobile systems. First off, power draw. Mobile workstations must be designed to draw as little power as possible, since the system must be able to run adequately off a battery pack when there is no A/C outlet nearby.

The figures below were recorded at the wall outlet using a Kill A Watt meter. GPU loading was done using the Unreal 4 editor, CPU loading by rendering with mental ray inside Maya, and CPU and GPU loading by rendering with Iray inside 3ds Max.

Although the ZBook 17 G2’s power draw is roughly double than that of its 15-inch sibling, it is still quite low, especially when compared to equivalent desktop systems.

At idle, it pulls 36W from the wall outlet. With the GPU at full load, the system pulls 102W; with the CPU at full load, 124W; and with both the CPU and GPU at full load, it pulls 167W.

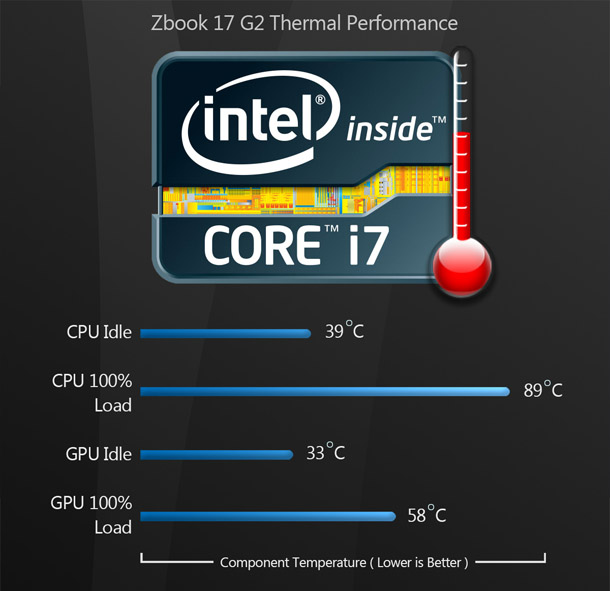

Thermal performance

Thermal performance is critical for mobile workstations. With all of the internal components squeezed together into such a tight space, poor cooling performance can spell death to an over-used machine – not to mention the fact that a mobile system that heats up significantly can become quite uncomfortable to use when working on your lap, or when resting your hands on the keyboard and trackpad for any length of time.

Here, the ZBook 17 G2 performs very similarly to the ZBook 15. Under heavy load, the internal components can get quite hot (in my view, uncomfortably so), but the outer chassis stays nice and cool to the touch, aside from the exhaust fan cooling vent.

HP claims that all the internal components run within safe thermal ranges, but I would be nervous about using this system with any applications that are going fully load the CPU for long periods of time: under such conditions, the CPU averages 89°C and can spike up to 94°C. Intel’s recommended maximum operating temperature for many of its CPUs is in the 90-95°C range, so pushing hardware that close to its limits seems likely to risk decreasing overall CPU lifespan, although I’m not aware of any tests that have quantified this.

As I have noted in previous reviews, operating the workstation on a laptop stand with cooling fans underneath brings down the CPU temperature by an average of 4-5°C, so I would recommend that here.

Battery life

The ZBook 17 G2 uses an eight-cell 83WHr Lithium ion battery pack. Like many other mobile workstations, battery life is reasonable during normal use, but tax the CPU or GPU with any kind of graphics work, and it diminishes quite rapidly.

With light-load tasks (primarily internet browsing, plus some use of Microsoft Word and Excel and 1080p video playback), battery lifespan averaged just over five hours. Pushing the CPU to 100% load with DCC work or rendering reduced this figure to roughly an hour and a half. If you have any moderately complex render, or a simulation that you know will take more longer than this to complete, make sure you have a wall outlet handy.

Remote Graphics Software

As well as its hardware, HP offers its business customers software solutions aimed at increasing productivity and streamlining workflows. One such solution is its Remote Graphics Software (RGS), currently on version 7. In simplified terms, remote desktop-access software enables the user to control a computer remotely from another computer or dummy terminal via a TCP/IP connection, meaning that laptop or even tablet users can make use of the processing power of a higher-end system.

There are a lot of commercial remote-access software packages out there, but HP’s is optimised for heavy graphics tasks, meaning the the receiver updates more smoothly when running graphically intensive applications like 3D, video editing and video playback software.

The only disappointing thing about RGS is that it only works over a local network, not via the internet. It would be useful if professionals working in the field were able to log into the machines in their studio’s data center.

Overall conclusion

I have spent the last few months incorporating the ZBook 17 G2 into my daily workflow to get a feel for how it holds up in real production environments and determine its viability as a desktop replacement. So how does it stack up? In a word, superbly!

Configured as our test system is, the ZBook 17 G2 easily matches and even outclasses the other quad-core systems I use in my day job. For raw performance, the only desktop systems that beat it are super-high-end workstations with more than six CPU cores; or enthusiast quad-core systems with multiple, overclocked CPUs.

My only worry with the ZBook from a performance standpoint is the thermal characteristics of its Core i7 CPU. The system runs very hot under load, and there isn’t much data available to say how well Haswell processors hold up when pushed to their thermal limits over long periods of time.

The ZBook 17 G2’s ergonomics are also good. The track pad is quite large, allowing for more precise cursor control, and the keyboard is comfortable and easy to use. The flat keys are light to the touch, requiring little effort to depress, and as with the ZBook 15, the backlighting on the keys is a nice addition.

I liked the ZBook 15’s simple, clean, high-capacity chassis design, and since the ZBook 17 G2 is basically a larger clone, the same is true here. It’s an attractive system, and one that is sturdy and easy to work with. When you also take into account the case, power adapter and any peripherals you need, it’s a little on the heavy side to carry around for long periods of time, but that’s a minor gripe.

Couple this with HP’s service and support and the Remote Graphics Software, and the ZBook 17 G2 is a great mobile system. The $6,000 price tag is a bit on the expensive side, but when you consider the 30-bit colour display and top-of-the-line Quadro GPU – and the usual premium you pay for a mobile workstation – it’s in line with equivalent systems.

I would recommend the HP ZBook 17 G2 to any media or content creation professional who needs an extremely powerful system in a mobile form factor. If you’re in the market for a no-compromises 17″ mobile workstation, and it fits into your budget, look no further. Equipped with the components listed above, it is hands-down the most powerful mobile workstation I’ve worked with to date.

Jason Lewis has over a decade of experience in the 3D industry. He is currently Senior Environment Artist at Obsidian Entertainment and CG Channel’s technical reviewer. Contact him at jason [at] cgchannel [dot] com

Read more about the ZBook 17 G2 on HP’s website

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following vendors and individual artists who contributed to this review:

Nvidia

Chaos Group

Autodesk

Adobe

Gnomon School of Visual Effects

Obsidian Entertainment

my.com

Oliver McIntosh of Porter Novelli

Lora Shook of HP

Stephen G Wells