Review: HP Z210 workstation

HP’s entry-level Z210 workstation may be marketed as a machine for CAD and lower-performance DCC work, but its performance almost rivals that of its more expensive siblings. Jason Lewis puts it through its paces.

In this review, we will be taking a look at HP’s entry-level workstation, the Z210. For those of you who have been following my reviews for the last three years, you will know that I am a fan of these high-end desktop systems. I have personally tested and reviewed every other model in HP’s current line-up: the Z400, Z600 and the Z800.

2011 was an interesting year for HP, with the announcement that the company was thinking of selling off its Personal Systems Group, the division responsible for all its PC systems, and focusing on enterprise-level business software. This idea was baffling, not only to me, but to most of the PC and business community, as HP was, and still is, the largest distributor of PC systems in the world by sales volume. The company cited increasing competition and low margins as its main reasons for wanting to sell off the PSG. But despite this, the group brings in a net income in the billions each year: a pretty lucrative business, and one that it is curious the company should want to offload.

HP has since decided not to proceed with the sale, stating that retaining the PSG is the right move for its customers, partners, and shareholders. This is undoubtedly true, but the real explanation – according to several market analysts, at least – is that HP’s shareholders were very unhappy about the idea of dumping a division that makes a lot of money; and moreover, the company simply could not find anyone who could afford the asking price. Whatever the reason, I was relieved to learn about the change of heart, as a large percentage of the professional CG industry relies on HP workstations, and a sudden disappearance or change of ownership would have the potential to disrupt the work of a number of the largest effects and animation studios.

Buy or self-build?

Before we get to the meat of the review, I have had a number of readers ask what is more cost-effective: purchasing a system from a high-profile vendor such as HP, or building one yourself? While that seems a straightforward question, there are actually several issues that make that issue more complex.

The biggest of these, and one primarily relevant to individual users, is that while most CG professionals are tech-savvy, not everyone has the ability or desire to go through the headaches of putting their own system together. In addition, by purchasing a workstation from a vendor, you gain access to its support staff. This is the factor that makes vendor systems so much more appealing to professional studios when the IT departments are responsible for managing thousands to tens of thousands of systems, and support plans become a critical issue. Many large studios go further, and partner with system vendors to develop new technologies that will enhance their pipelines: HP?s partnership with DreamWorks Animation being a case in point.

There is clearly money to be saved by building your own system, but how much depends on how you want your system to be configured. If you compare a vendor-built system to a self-built system with identical specifications, the cost difference will be quite small. These savings diminish further when you start looking at higher-end multi-socket workstations with professional graphics accelerators.

The real benefit that self-building offers is the option to use consumer-level hardware in place of the more expensive professional components offered by workstation vendors as standard: for example, a Core i7 CPU instead of a Xeon, or a GeForce or Radeon graphics card instead of a Quadro or FirePro. But as I mentioned before, without vendor support, once you start having technical difficulties, you are on your own.

If you are comfortable with hardware and don’t mind being your own IT department, go ahead and build your own system: you’ll save a little bit of money, and you will have the satisfaction of being able to set up your system with exactly the brand and type of components you want. If, however, you just want a high-quality workstation and have it work, I would highly recommend a system from a reputable vendor such as HP (or Dell, Lenovo, Boxx, or the many other specialist firms available). I have personally done both, and while I used to be all about self-building, having used HP systems for the past few years, have come round to the idea of a workstation I don?t have to troubleshoot myself.

System specifications

With that out of the way, let’s get to the review itself. The Z210 is HP’s entry level workstation, and it is marketed at CAD and industrial designers, architects and entry-level CG, animation and compositing. It comes in two form factors, the Small Form Factor, and the Convertible Mini Tower, which is the one we will be reviewing here.

The Small Form Factor packs all the same components as the larger CMT into a case that measures just 13.30 x 3.95 x 15.00″ (33.8 x 38.1 x 10 cm) – with the exception of the graphics card. Due to the small size of the case, the SFF system can only equip half-height cards such as the Nvidia Quadro 600 and the AMD FirePro V3800, which are only suitable for the most basic CG tasks. In contrast, the CMT is basically just a mid-tower system and can accommodate more powerful full-sized cards such as the Nvidia Quadro 4000 and the AMD FirePro V5800. Although the Z210 is targeted at entry-level animation work, in reality, equipped with the right graphics hardware, it could tackle much more substantial CG tasks.

The Z210 follows HP’s current design trend with a simple black front panel with vertical black slats. Unlike the Z600 and Z800, which sport attractive brushed aluminum sides, the Z210 just has a solid black case. Connectivity is pretty standard, with six external USB 2.0 ports, an eSATA port, audio jacks, a Gigabit Ethernet port, a DVI-I port for on-board graphics, and legacy PS/2 mouse and keyboard ports on the rear panel. The front panel offers three external USB 2.0 ports, a FireWire 1394 port, and headphone and mic jacks.

Opening up the case reveals a simple, well-laid-out interior featuring HP’s standard tool-less construction, which enables you to remove the hard drives, and graphics/expansion cards without the need for a screwdriver: nice for those of us who swap out these components frequently. The interior also contains a 400W Energy Star 5.0 power supply with a 90% efficiency rating.

Test procedure

Our test Z210 system sports a Xeon E3 1270 quad-core CPU running at 3.4 GHz on a custom-built motherboard running an Intel ID0108 chipset. It is equipped with 8GB of RAM, a 160GB Intel SSD system drive, and a Seagate 1TB data drive. It is running a Nvidia Quadro 2000 GPU.

For comparison, we also tested the following systems:

An HP Z800 with two six-core Xeon X5680 CPUs running at 3.33GHz, 18GB of RAM, and an Nvidia Quadro 6000.

A coach-built system with an Intel Core i7-980 six-core CPU running at 3.3GHz, 12GB of RAM, and an Nvidia GeForce GTX 460 GPU.

A coach-built system with an Intel Core 2 Quad Q9550 quad-core CPU running at 3.0GHz, 8GB of RAM, and an AMD FirePro V8800 graphics card.

For benchmarking, we used the following standard suite of DCC and rendering applications:

DCC packages

3ds Max 2012, Maya 2012, Softimage 2012, Mudbox 2012, Photoshop CS5.1, Fusion 6.2 LE, ZBrush 4

CPU-based renderers

mental ray 3.9, V-Ray 2.0, Brazil r/s 2.0, Maxwell Render 2.5

GPU-based renders

iray, FurryBall 2.3

Synthetic benchmarks

CineBench 11.5

All testing was performed with an HP LP3065 30″ LCD monitor running at its native resolution of 2,560 x 1,600.

Benchmark results

3ds Max 2012

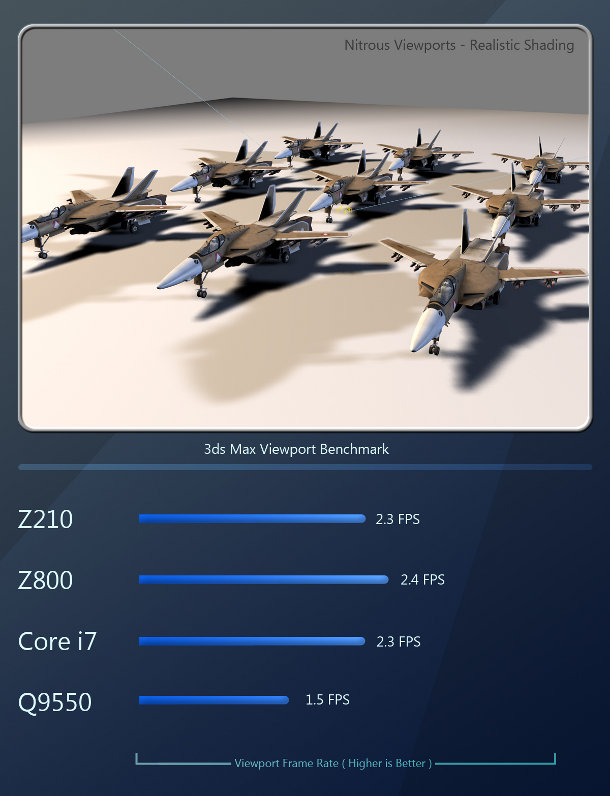

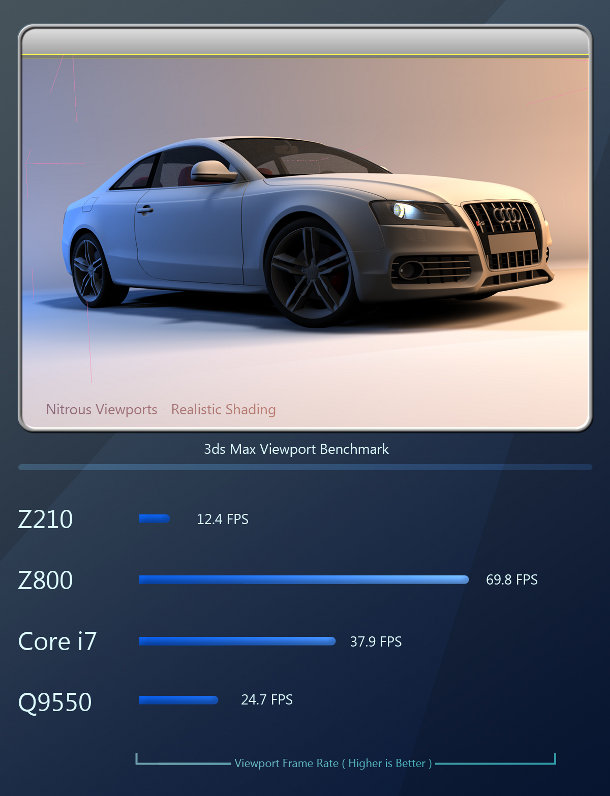

First up, we have the 2012 version of Autodesk’s 3ds Max modeling, rendering and animation software. Together with Maya, it makes up a little over 80% of the DCC market. The following benchmarks show average viewport frame rates for rotating, panning, vertex and face editing for each model displayed. All were performed with the Nitrous viewport?s Realistic shading mode.

As you can see, the Quadro 6000 in the Z800 takes the lead here, followed by the GTX 460, the Quadro 2000, and lastly, the V8800 in the Q9550 system. (If you read my last professional GPU review, you will remember that 3ds Max seems to favor Nvidia over AMD GPUs.) While the Quadro 2000 falls behind the Quadro 6000 and the GTX 460, it still provides acceptable performance in the benchmarks, except for the scene showing the fleet of jet aircraft – one that all four of the cards struggled with.

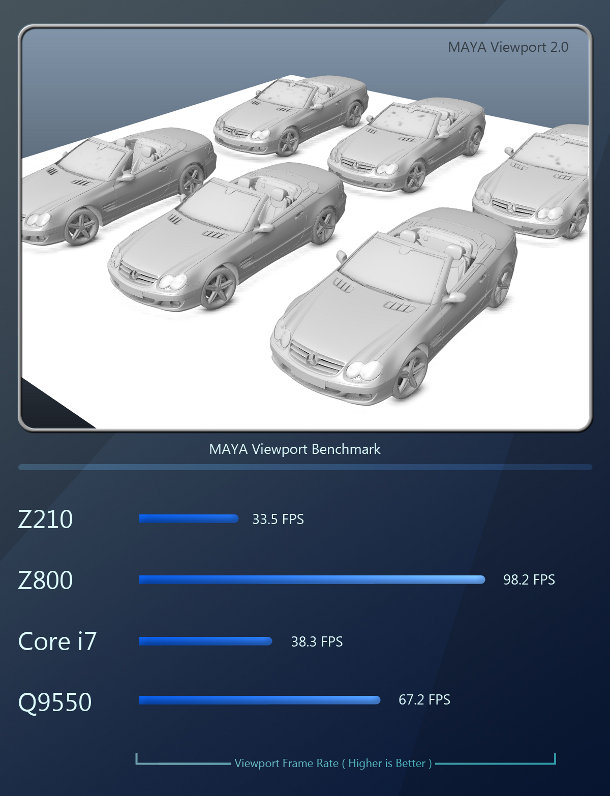

Maya 2012

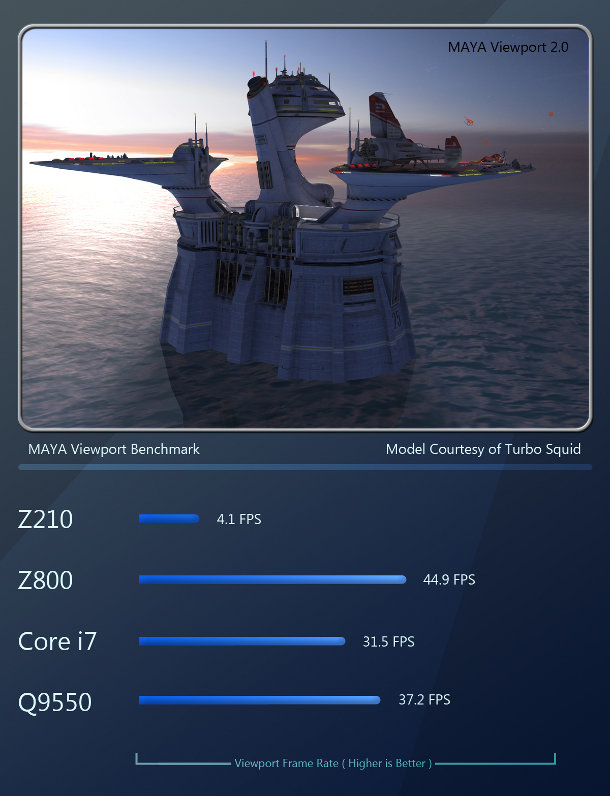

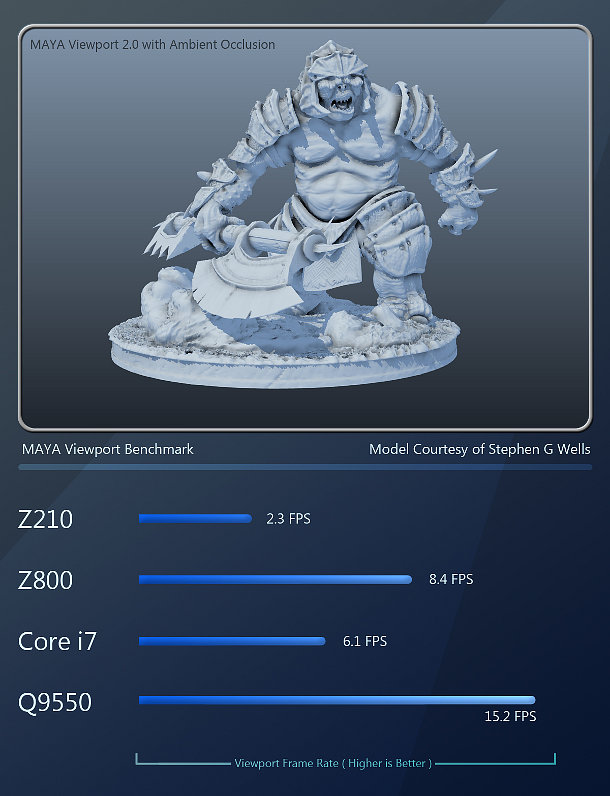

As with the 3ds Max benchmark, the Maya benchmark is also comprised of averaged viewport frame rates for rotating, panning, vertex and face editing for each of the models shown.

Again, the Z800?s Quadro 6000 comes out on top, followed by the Q9550 system?s V8800. (Again, based on my previous GPU review, Maya seems to favor AMD over Nvidia cards, with the exception of the massive Quadro 6000). In third place comes the six-core system with its GTX 460 card, and lastly the Z210 with the Quadro 2000. While the Quadro 2000 seems to handle raw polygon pushing quite well, it suffers a bit in the shader-heavy landing pad scene.

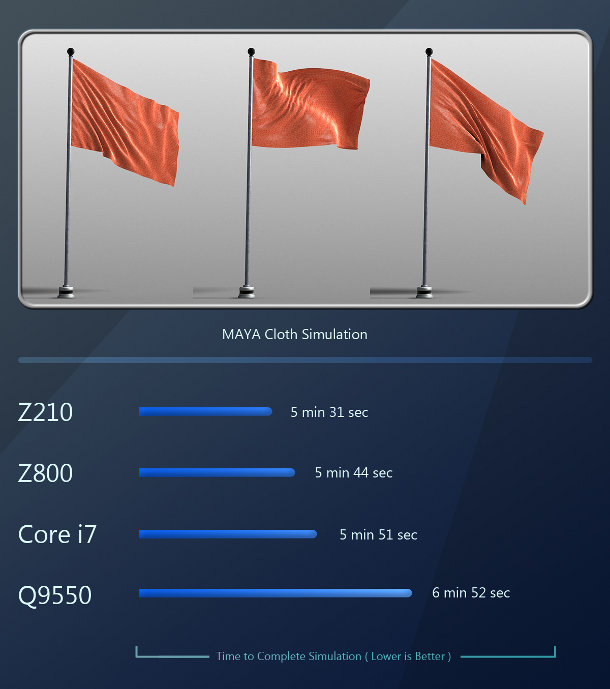

Maya cloth dynamics

Next we have a cloth simulation done with Maya 2012’s cloth dynamics tools. The simulation is a basic flag with a Gravity and Wind force applied to it, simulated over 140 frames of animation.

Maya Cloth is not multi-threaded (at least, it didn?t spawn more than one thread on any of my test systems while performing the simulation), so the only factors affecting this benchmark were clock speed and CPU architecture. Accordingly, the Z210 takes first place with its 3.4GHz CPU, followed closely by the Z800 with its 3.33GHz CPUs and the Core i7 system with its 3.3GHz CPU; and by a larger margin, the 3.0GHz Q9550 system. The performance of the Z210, Z800 and Core i7 systems are very similar: only the Q9550 system, with its much lower clock speed and older CPU architecture, falls significantly behind.

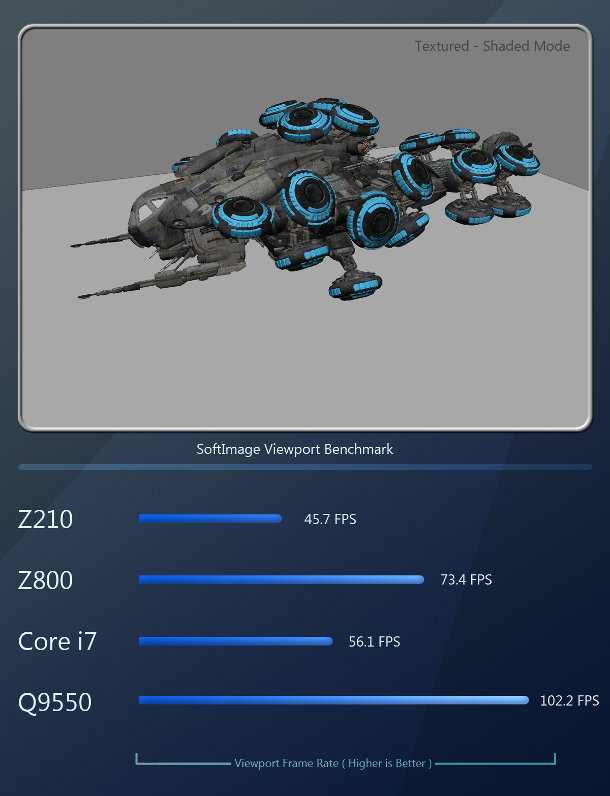

Softimage 2012

Softimage is the third DCC application in Autodesk?s line-up. It is a full-featured 3D modeling, animation and rendering package. Again, the benchmark consists of averaged frame rates for viewport rotating, panning, vertex and face editing for the scene shown.

Like Maya, Softimage seems to favor AMD GPUs. Even the Z800, with its powerful Xeon CPUs, gets beaten by the V8800 in the Q9550 system. Next we have the Core i7 system; and Z210, with its Quadro 2000, follows closely behind.

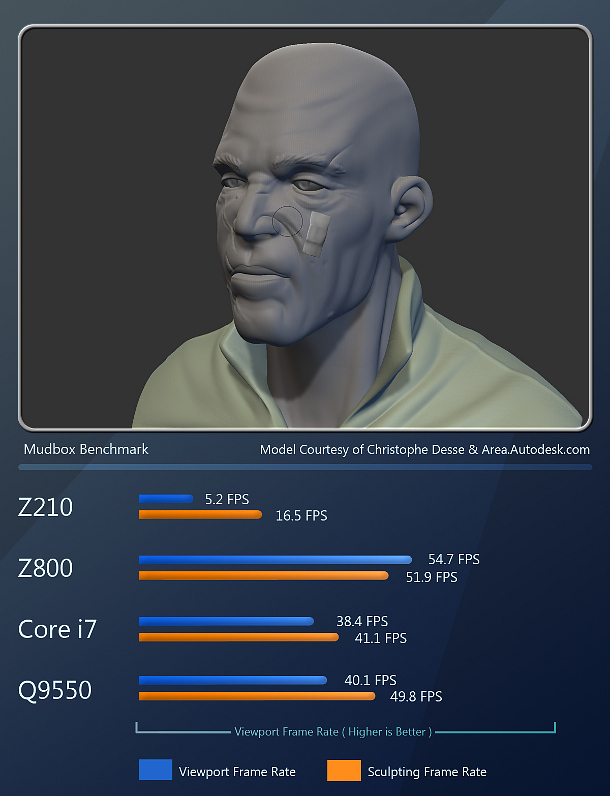

Mudbox 2012

The last piece of Autodesk software used for our Z210 benchmarks is Mudbox 2012. Unlike 3ds Max, Maya, and Softimage, Mudbox is a digital sculpting program similar to ZBrush. Sculpting applications tend to be optimised to display much higher polygon counts than their traditional DCC cousins. With this benchmark, we will look at simple viewport performance, as well as sculpting performance.

All of the previous benchmarks show that the Z210?s Quadro 2000, while slower than the other test systems? GPUs, still offers perfectly usable performance in most situations. However, Mudbox performance does not follow this trend. The entry-level GPU and the lower 1GB of RAM severely limit Mudbox’s performance on the Quadro 2000 card.

ZBrush 4

ZBrush, like Mudbox, is a digital sculpting application. But whereas Mudbox taxes both the CPU and GPU, ZBrush only uses the CPU to render geometry to screen. As with Mudbox, I attempted to run two benchmarks for ZBrush: viewport performance, and sculpting performance.

Unlike Mudbox, ZBrush performs quite well on the Z210: the fast quad-core CPU in the Z210 gives the software plenty of horsepower to work with. Unfortunately, there is no way to view or record frame rate in the ZBrush viewport while sculpting an object (at least, not one that I am aware of: if you know of one, please post it in the comments to the review). Fraps will not give a readout in ZBrush, possibly because ZBrush uses its own rendering system rather than OpenGL or DirectX, so Fraps doesn’t see it as a 3D application. All I can really do here is convey my personal experience of using ZBrush on the Z210 workstation, and I will say that it seems to have plenty of horsepower for running moderate-to-high-detail meshes.

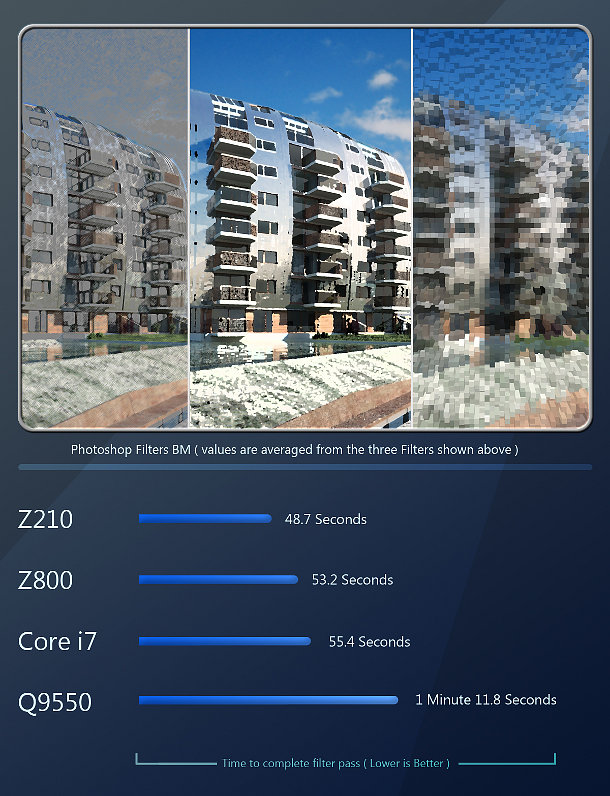

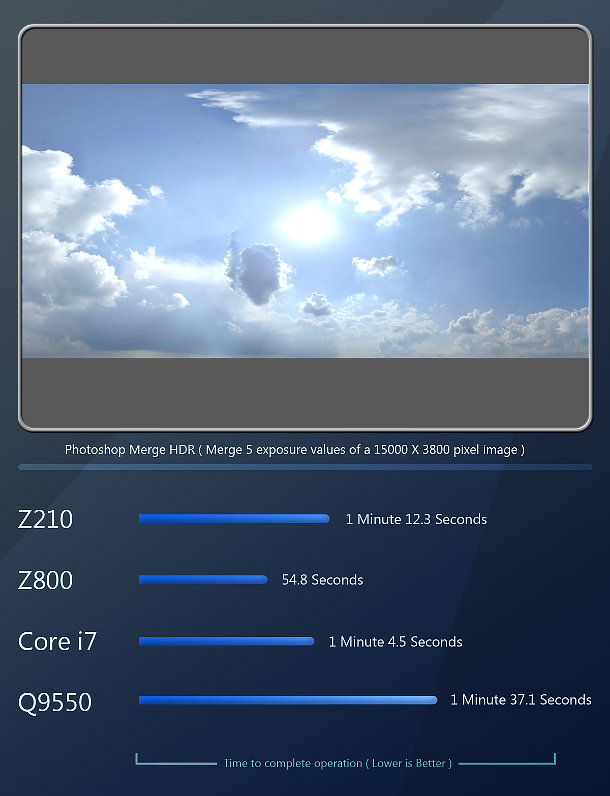

Photoshop CS5.1

Photoshop is the industry-standard 2D image-editing tool. There is no real way to quantify editing performance within Photoshop, although the speed and fluidity of editing and painting operations ‘feels? similar in three of the the test systems, with the Q9550 perhaps slightly less responsive. However, we can quantify the time it takes each workstation to run Photoshop filters on large images.

Photoshop filters and effects are single-threaded, so again, the Z210 takes first place with its 3.4GHz CPU, followed by the 3.33GHz Z800 and Core i7 systems, and lastly, the 3.0GHz Q9550 system. Again, notice how close the results are for the Z210, Z800, and Core i7 systems. The HDR image processing was a little different, with the Z800 taking first place, followed by the Core i7 system, and right behind that, the Z210; and lastly the Q9550 system.

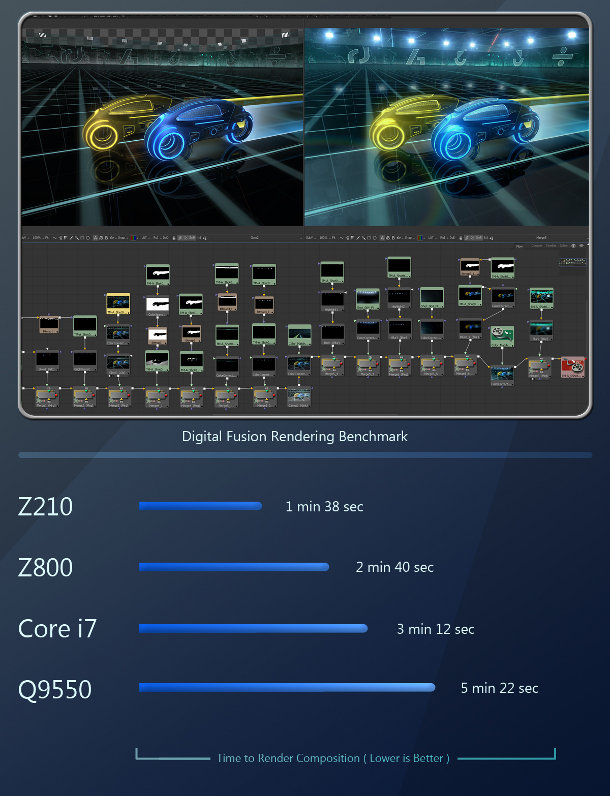

Fusion 6.2 LE

Fusion is a node-based compositing application. For this benchmark, we have a moderately complex composition that is 141 frames long, rendered at HD 720 resolution.

The Fusion rendering benchmark yields some interesting results, as the Z210 takes first place, followed by the Z800, and close behind, the Core i7 system. Last comes the Q9550 system.

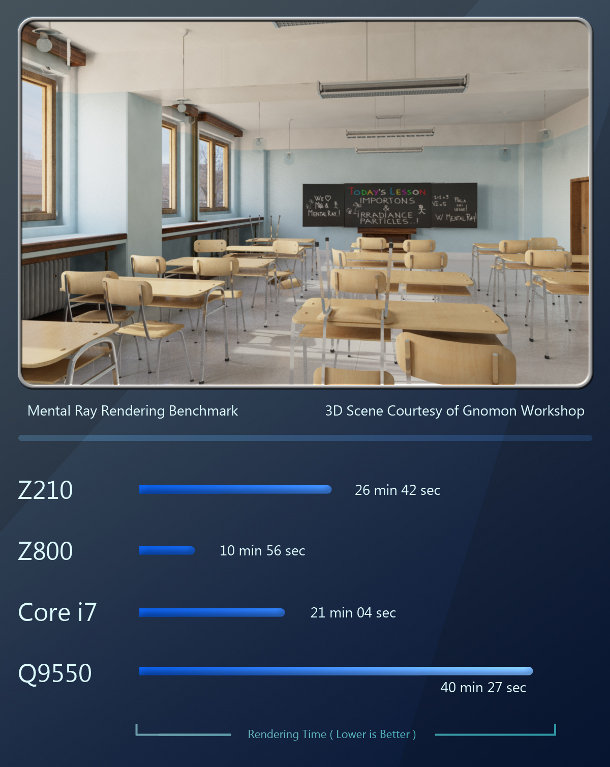

mental ray 3.9

Our first rendering benchmark is mental ray 3.9. Together with Pixar’s RenderMan, it makes up a large percentage of the rendering market for visual effects and animation. (While there are no RenderMan benchmarks in this article, look out for a review of RenderMan Studio in coming months.)

Rendering software is one of the few types of applications that is heavily threaded and therefore highly optimized for multiple CPUs/CPU cores. Scaling is almost linear with each additional core, with slight diminishing returns once you go above four. The 12-core Z800 system takes first place, followed by the six-core i7 system. The four-core Z210 takes third place, and last comes the four-core Q9550 system with its older CPU architecture.

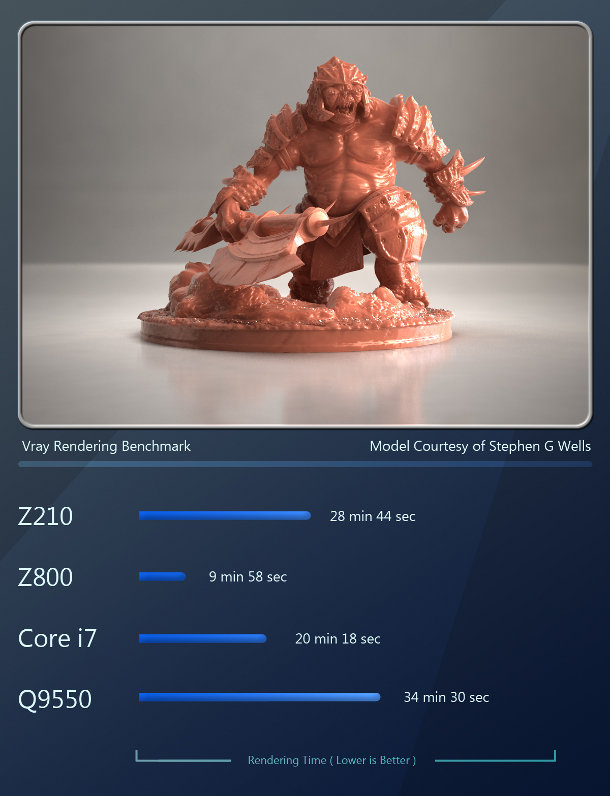

V-Ray 2.0

V-Ray is a third-party renderer for 3ds Max, Maya, Softimage, SketchUp and Rhino. We reviewed the latest version of the software for 3ds Max last year.

As with the mental ray benchmarks, V-Ray’s performance increases significantly as you add more CPU cores. Again, the Z800 comes out on top, followed by the Core i7, the Z210 and the Q9550.

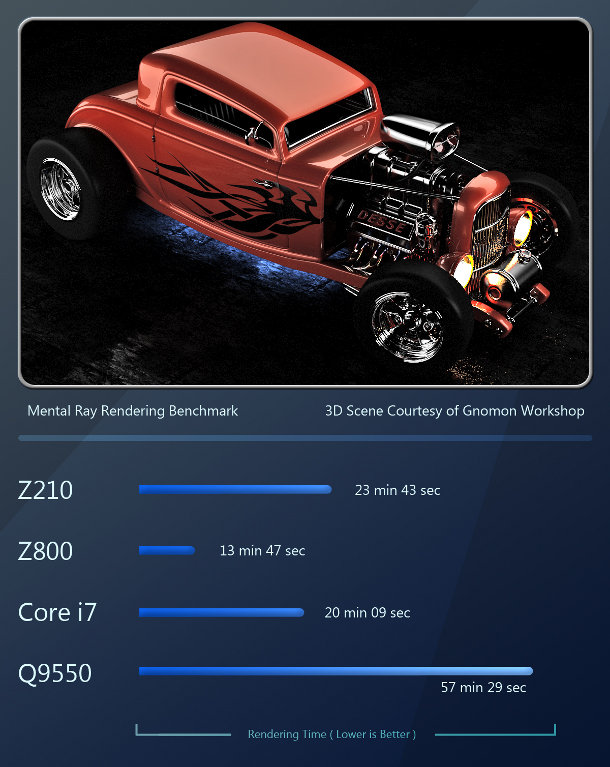

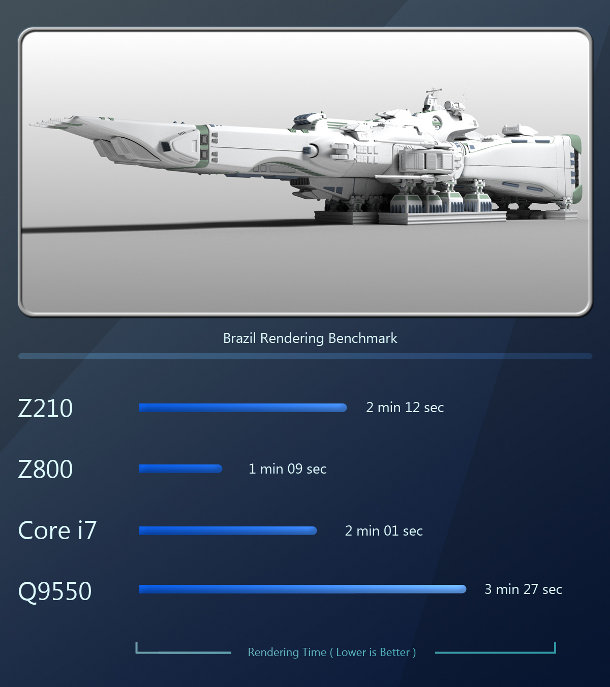

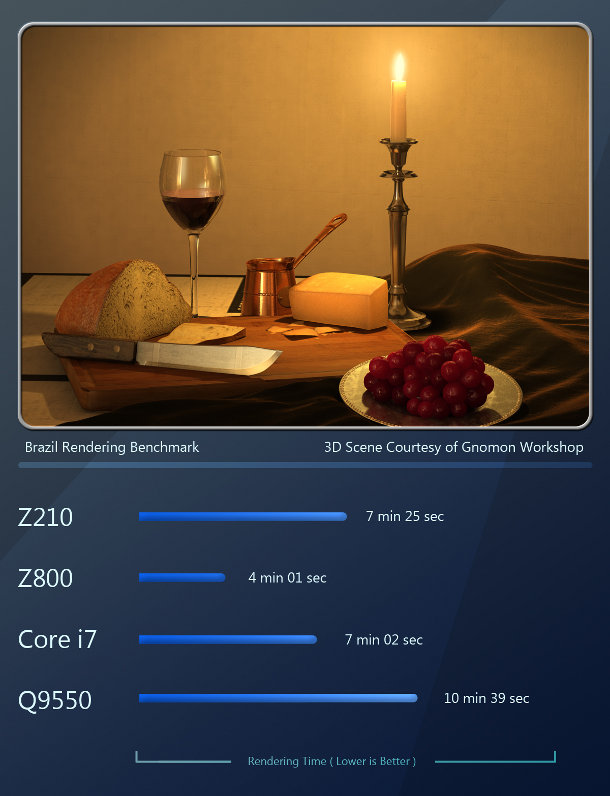

Brazil r/s 2.0

Brazil was one of the first GI renderers to become commercially available. Its developer is working on support for GPU acceleration in version 3, but for now, rendering calculations are CPU-based.

The same rule as the previous two CPU rendering benchmarks holds true here: 12 cores beats six, which beats four, which in turn beats four based on older architecture.

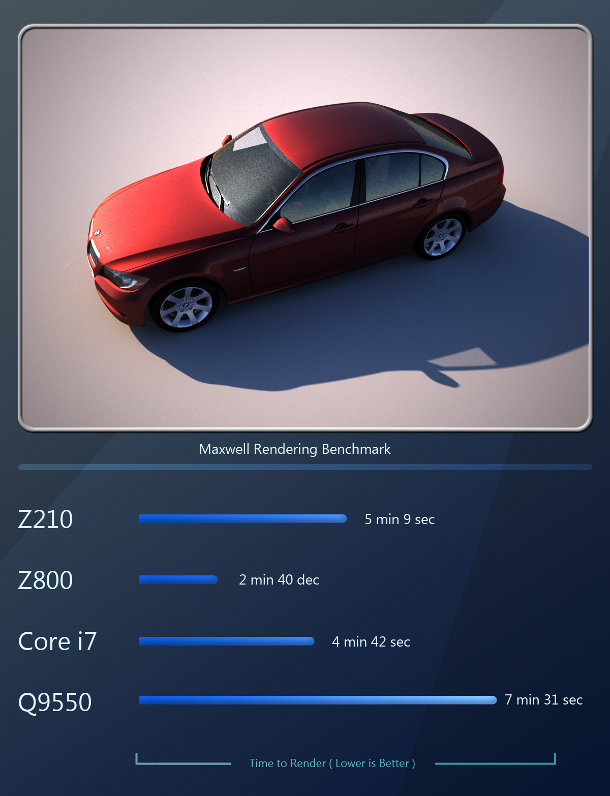

Maxwell Render 2.5

Maxwell Render was one of the first commercial renderers based on unbiased rendering technology. Unbiased renderers have the advantage of a much simplified user experience and realistic output, but are significantly slower than their Reyes-based counterparts.

Again, the results follow the same pattern as with mental ray, V-Ray and Brazil r/s: the 12-core Z800 beats the six-core i7, followed by the four-core Z210, and lastly the Q9550 machine.

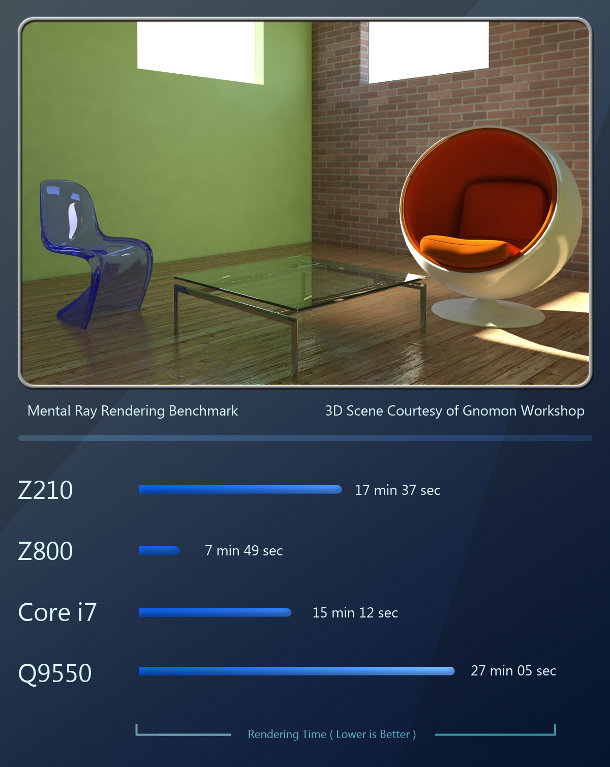

iray

iray is an unbiased renderer developed by Nvidia. It is currently the most popular GPU-accelerated renderer on the market today. It is integrated into 3ds Max 2012.

iray shows similar results to the other rendering benchmarks as it is designed to use all available CPU cores as well as all available GPUs present in the host system. Again, the 12-core Z800, with its powerful Quadro 6000 GPU, takes first place; followed by the six-core i7 system, with its GTX 460 GPU; then the four-core Z210, with its Quadro 2000; and lastly, the Q9550 with the FirePro V8800.

(In terms of raw processing power, the FirePro V8800 should have been enough to put the Q9550 in either second or third place. However, iray uses Nvidia’s CUDA API, which is not supported by AMD GPUs, and therefore when rendering the iray scene on the Q9550, only the system’s CPU is used for calculations.)

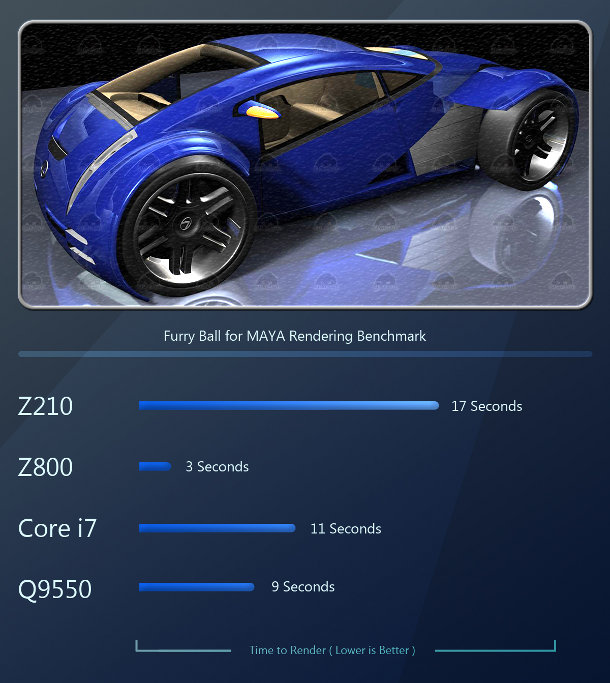

FurryBall 2.3

Like iray, FurryBall is a third-party GPU-acclerated renderer: in this case, a biased renderer for Maya. Again, we aim to review version 3.0 when it is released later this year.

FurryBall differs from iray in that it is built upon the open OpenCL standard rather than CUDA, and therefore can take advantage of both Nvidia and AMD GPUs. The Z800, with its mighty Quadro 6000, again takes first place, but whereas the Q9550 system came last in all of our previous rendering benchmarks, here it takes second place thanks to its powerful FirePro V8800. The GTX 460 GPU in the Core i7 system takes third, and the Z210’s Quadro 2000 puts it in fourth place.

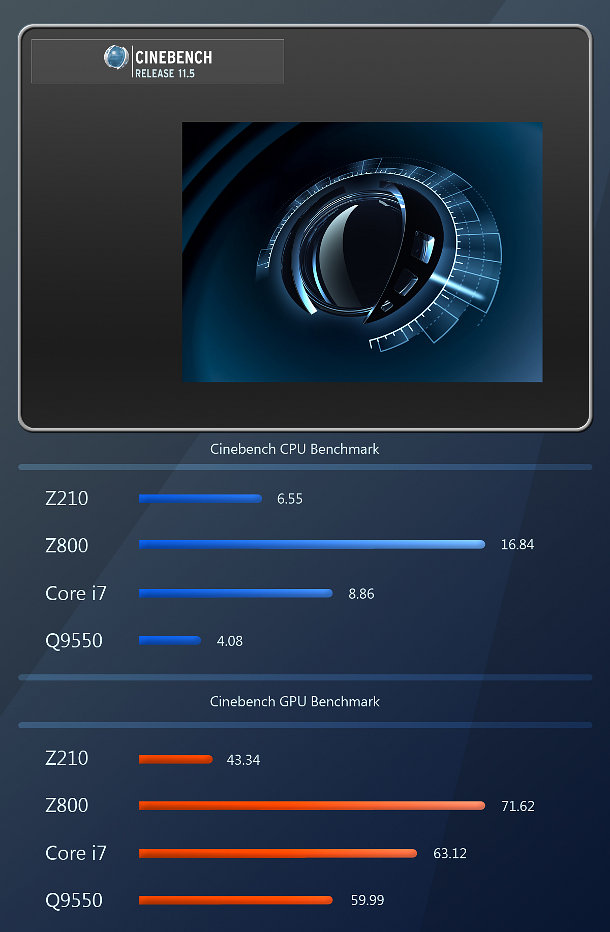

CineBench 11.5

Those of you who are familiar with my previous reviews will know that I am not a fan of the synthetic benchmarks that so many other reviewers rely on. This is simply due to the fact that the results they generate do not reflect the performance you would find in real production situations. Despite this, I have had requests from readers to include CineBench results, so it is the one synthetic benchmark I include. You can download it here.

The CineBench CPU benchmark is highly optimized for multi-threading, so core counts win out over clock speed. The Z800’s 12 CPU cores take first place; the Core i7 system with its six-core CPU takes second; the Z210’s fast quad-core CPU comes in third; and the Q9550, with its slower clock speed and older architecture, takes fourth. GPU benchmark results are similar, with the Quadro 6000 in the Z800 taking first place and the GTX460 in the Core i7 system taking second, although this time, the Q9550 system?s FirePro V8800 comes in third, ahead of the Z210 with its Quadro 2000.

Noise, boot-up time and power consumption

Lastly, let’s take a look at some of the other important features of any workstation, aside from raw speed. The first of these is acoustic performance. Vendors are constantly pushing for quieter systems: a welcome benefit to all of us who use powerful workstations. In this arena, the Z210 excels. Even under full CPU load, you can only really hear any fan noise if you put your head right up to the system. The only audible noise that comes from the system is the cooling fan on the Quadro 2000 when it is stressed with heavy scenes or GPU computing tasks.

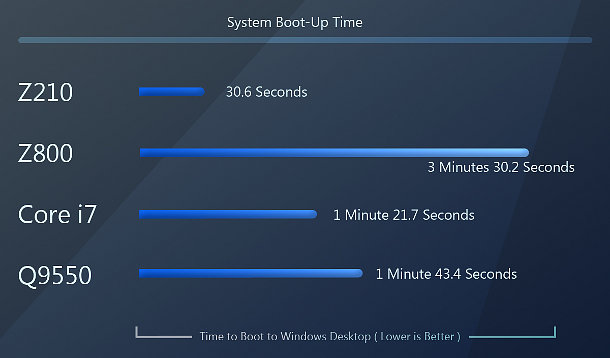

Next we have boot-up time. I must admit, I was quite astonished with the boot-up time of the Z210 the first time I powered it on. I assume this has to do with the fast SSD that is used as the primary boot drive, as SSDs offer vastly superior read performance over their spinning-media cousins.

As you can see from the chart above, the Z210 commands a significant lead over the other systems in boot-up time, with the six-core Xeon system taking second place, the Q9550 system in third, and lastly the Z800.

There are several factors that can affect boot times, including the amount and type of hardware and software installed on the system. The Z800 is my primary software test machine, so it has double the number of software packages installed on it compared to the Z210. Nevertheless, the Z210?s SSD seems to give a significant performance boost here.

Over the years, I have used many dual-socket systems, and it seems that overall, systems sporting a dual-socket motherboard with both CPU sockets filled seem to boot up slower than single socket systems, regardless of the number of CPU cores within each CPU.

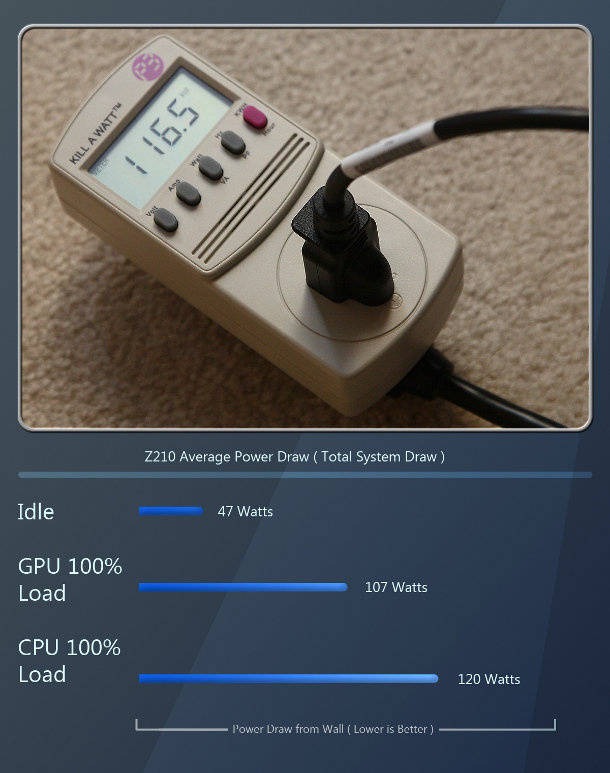

Lastly, let’s look at power draw. With the ever-increasing costs of electricity, power usage has become a very real concern when choosing a new workstation. While it is true that throwing more and faster hardware at a system will increase its performance, this also increases its power usage, and when you have an animation studio filled with hundreds of workstations, the difference between a system that draws 100W of power and one that draws 500W can mean thousands of dollars in electricity bills per year. Even for individuals, power usage can make a noticeable difference if you leave your system on all night, or even if you just use it frequently.

As you can see, the power-draw for the Z210 is very low. With its low-power Quadro 2000 and 32nm Sandy Bridge-based Xeon processor, even under full GPU and CPU load, its power draw is less than some high-end video cards alone. Other contributing factors to the Z210’s low power draw are the SSD hard drive and the 90% efficient power supply.

Overall verdict

HP touts the Z210 as a basic, entry-level system, and compared to the more powerful Z-series workstations, it might be. But if you step back and look at it by itself, it is much more than this. The Z210 performed well in all of the software tests that it was put through for this review, offering solid performance in modeling, texturing, Photoshop work, compositing and digital sculpting (in ZBrush, if not in Mudbox).

The only area the Z210 does not offer competitive performance in is rendering. Its Xeon E3 1270 is a good performer, and could stand up to some of the fastest consumer quad-core CPUs on the market. However, rendering scales very well with number of cores, so no quad-core can stand up to a six-core CPU, let alone a dual-socket workstation with multiple quad or six-core CPUs. If you are a render junkie like myself, you might want to think about spending a little extra for a Z400 with its six-core CPU; or even a lot extra for the dual-socket Z600 and Z800.

I would also be tempted to spend a bit more on a higher-end graphics card. While the Quadro 2000 performs adequately in light-to-medium scenes, with only 1GB of RAM, it struggles with denser scenes. Its limited RAM also restricts its usefulness for GPU-based rendering. My personal choice here would be either the Quadro 4000 or AMD?s FirePro V5900.

But overall, the Z210 is a solid system that deserves a serious look if you are in the market for a lower-cost workstation. It is quick, quiet, has very low power consumption, and you get access to HP’s top-notch support department. It is another high-quality entry in HP?s Z-series line-up of professional workstations.

Jason Lewis has over a decade of experience in the 3D industry. He is currently Senior Background Artist at Electronic Arts and CG Channel’s regular technical reviewer. Contact him at jason [at] cgchannel [dot] com

Read our reviews policy FAQs document

Future reviews

Before I sign off, I want to take a moment to talk to those of you familiar with my previous reviews. As you may know, I am a CG artist first and a journalist second, and I started writing these reviews to try to give the CG community something that I had long been looking for, but could never find: in-depth hardware reviews with benchmarks geared specifically for DCC artists. General hardware sites such as Tom’s Hardware and AnandTech do a great job, but they can?t hope to provide the specialist benchmarks that CG artists really need.

So I would also like to say thanks to all of you who post comments on my reviews. They are very valuable, and have helped shape some of the content in these articles. If you feel that there are any aspects of the testing process that have been overlooked or need to be expanded on, feel free to post suggestions in the comments.

If there are any specific applications, plugins, hardware components or workstations that you all would like to see reviewed in future, let me know. I will be tallying all of your requests over the next few months, and will take the most requested reviews to their respective vendors.

For example, there has been a curious lack of rendering benchmarks for AMD Opteron CPUs. While Intel CPUs are typically faster per core, the AMD chips have much higher core counts per CPU, so I would be curious to see how they fare with multi-threaded software. If any of you feel the same way, let me know and I will ask AMD if they would be willing to participate.

And finally, if you enjoyed this review, please feel free to say so. Constructive criticism is great, but it?s also nice to hear that people appreciate these articles!

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following vendors who contributed to this article:

Autodesk

Adobe

Chaos Group

SplutterFish

Pixologic

Art And Animation Studio

Next Limit