The twisted tale of The Voice in the Hollow

The Voice in the Hollow isn’t your average animated short. A 3D animation styled like a 1970s grindhouse movie, it transplants the biblical story of Cain and Abel to East Africa, recasting the protagonists as teenage girls, and retelling their bloody tale of sibling jealousy and murder in Swahili.

It’s also a new departure for the professional and personal partnership of Miguel Ortega and Tran Ma, the duo of visual effects artists best known for The Ningyo, their ambitious episode-length 2017 live-action short about a turn-of-the-twentieth-century cryptozoologist on the hunt for a mythical Japanese mermaid.

Whereas Ortega and Ma’s previous productions were created using a conventional offline effects pipeline, The Voice in the Hollow, created over the course of a year of intense, obsessive work, exploits the new workflows made possible by Unreal Engine 5, Epic Games’ game engine and real-time renderer.

In this article, we explore how The Voice in the Hollow came to be created, how real-time film-making enabled its tiny production team to complete what would have otherwise have been an impossible project – and how, in a final twist in this already twisted tale, a film that Ortega and Ma regarded as deliberately, defiantly uncommercial is now winning major awards at festivals and praise from Epic Games itself.

The Voice in the Hollow’s premiere at Gnomon, the international CG school that produced the short. The production was documented in a series of weekly livestreams, archived on Gnomon’s YouTube channel.

Origins

Ortega and Ma began work on The Voice in the Hollow at a difficult time in their professional lives: the movie adaptation of The Ningyo, a project in which the pair had invested years of work, fell apart as productions were suspended during the initial COVID-19 restrictions.

“You think you’re days away from a life-changing moment, then you’re told the project is completely dead,” says Ortega. “It’s like a lottery ticket has been snatched out of your hands.”

The Voice in the Hollow was a reaction both to this experience – a desire to make a film for its own sake, without worrying about its commercial viability – and to that of life during lockdown.

“I feel that everybody was in a dark place at the time,” says Ortega. “That’s why the short is so dark.”

The budget for the short was provided by Gnomon, the award-winning VFX, games and animation college at which Ortega and Ma both teach, with Gnomon President Alex Alvarez acting as producer on the project.

Although Ortega and Ma had never used Unreal Engine in production – at the time, their only experience with the software had been through the 30-day Unreal Fellowship training program – the project, partly funded through Epic Games’ MegaGrants scheme, was an opportunity to explore new real-time workflows.

“Alex thought Unreal was going to be the future, and we agreed with him,” says Ortega. “We didn’t want to spend four years on another live-action movie, and having done the Fellowship, we knew that with a year, we could make something pretty cool.”

The core team behind The Voice in the Hollow: director Miguel Ortega and production designer Tran Ma.

Plot

A key inspiration for The Voice in the Hollow was California’s Moaning Caverns, where Ortega and Ma had shot scenes from The Ningyo, and the site of some of the oldest human remains to be discovered in North America. Before the caverns became a tourist attraction and the entrance was widened, air flowing through the caves created a moaning sound, leading to the legend that the noise was the voice of a young girl.

“Through the years, people would keep coming up to the hole to find out where the moans were coming from, and fall in … and it’s a 250 foot drop to the bottom,” says Ortega. “What’s crazy is that when they got to the bottom of the pile of bodies, there was a skeleton of a little girl.”

As well an explanation of how that skeleton came to be there, The Voice in the Hollow is a retelling of the biblical story of Cain and Abel, transplanting the action to East Africa, and translating Cain and Abel themselves into Coa and Ala, members of the fictional Great Leopard Tribe, with the voice that Coa hears in the hollow – and which feeds on her jealousy of Ala, leading her to kill her sister – standing in for the devil.

“It’s pretty fucked up,” admits Ortega. “To be a good storyteller, you have to be like the Old Testament God: grab your characters, make them go through hell, put every obstacle in their life, then at the end, kill them.”

Although neither of the film-makers had been to Kenya or Tanzania, and knew the area only through TV documentaries, Ortega says he was confident that the universal nature of the story would overcome any of the potential difficulties of setting the action in an unfamiliar location and an unfamiliar culture.

“Ultimately, all that matters is the human experience,” he says. “Everyone has felt envy, everyone has felt jealousy. We felt that if we hit those basic human flaws, everything would fall into place.

Visual references

If the setting for The Voice in the Hollow is African, the look is definitely Western, in more than one sense. Visual references for the film included The Great Silence, Sergio Corbucci’s bleak 1968 Spaghetti Western, along with grindhouse horror movies and brutal 1975 crime drama Framed.

“There’s something about 70s movies,” says Ortega. “People look sweatier and uglier.”

The film’s saturated colour palette, with its vivid reds, is a homage to another key figure in 1960s and 1970s cinema, the Italian director and cinematographer Mario Bava, whose horror anthology Black Sabbath was an inspiration for Ortega and Ma.

There’s even a nod to the look of 1970s movies in the opening credits to The Voice in the Hollow, where the traditional ‘Color by DeLuxe’ is replaced by the more contemporary ‘Color provided by Unreal Engine Five’.

Character design

The designs of the characters in The Voice in the Hollow draw inspiration from traditional African hairstyles and body painting, although not from any individual culture or ethnic group.

Ala and Coa are distinguished to the audience through the colour of their face paint, and through their clothing. Ala, the successful hunter, has a freer and more dynamic outfit, accentuated with pelts and leathers – “everything is a skin she’s hunted down,” says Ma – while that of Coa is simpler and more symmetrical.

The carved wooden leopard masks worn by the adults – the symbols of authority and parental favour that Coa covets – were inspired by those from Edo culture, with Ortega describing the result as “beautiful, but in a kind of goofy way”.

The look carries over to the characters themselves, which were modelled to look like carved wooden dolls. The figures were sculpted in ZBrush and textured in Substance 3D Painter, with Ma deliberately leaving her brush strokes visible to accentuate the angularity of the 3D models.

The materials use alpha masks, making it possible to generate variant colours for skin tones, body paint and clothing inside Unreal Engine, helping Ma and Ortega to populate shots with background characters, and the doll-like effect was heightened by rendering with shallow depth of field to make the characters seem smaller.

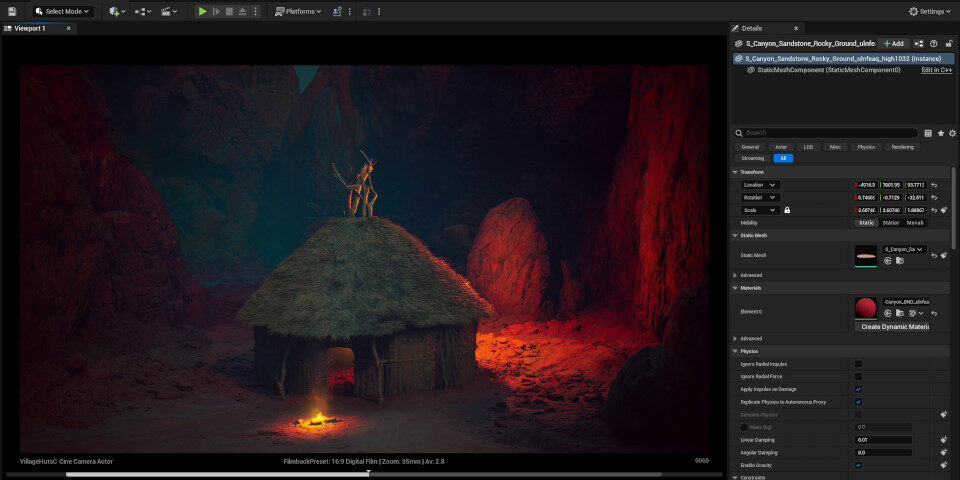

Environment design

Although the sisters’ village is only seen in a small number of shots, it was created as a complete 360-degree set, to provide maximum flexibility when choosing camera angles. To speed up the process, Ortega and Ma adopted a modular approach, generating variant designs for the huts using Maya’s XGen instancing toolset.

The base elements for the buildings, like planks and roof materials, are a mixture of stock assets from the Megascans library and hand sculpting in Mudbox, making it possible to create richly detailed environments without the need for a team of dedicated artists.

“It doesn’t matter if you see the detail. You have to feel it,” points out Ortega. “Even if a shot takes place in the darkness, you have to feel that there’s complexity there.”

The terrain around the hollow itself was created in Gaea, again making it possible to blend manual sculpting with procedural techniques, with the design nodding to that of the Sarlacc Pit in Return of the Jedi.

Voice acting

Although the script was originally written in English, Ortega and Ma quickly decided to switch to Swahili for the final recordings, as one of the languages most commonly spoken in East Africa.

Unable to find Swahili-speaking actors in Los Angeles, or suitable African talent agencies, the pair hit on the novel idea of hiring audiobook translators – not just to translate the script, but to voice the lead characters.

Although the main cast – Kenya’s Rosalie Akinyi and Tanzania’s Janeth Makungu and Goodluck Gabriel – didn’t consider themselves actors, Ortega says that they quickly nailed the vocal performances.

“They were amazing,” he says. “They didn’t require nearly as much direction as I thought.”

Motion capture

Motion capture for the short was recorded on the greenscreen stage at Gnomon’s Hollywood campus, using a Xsens MVN Awinda suit.

Ortega recorded placeholder animations for Coa and Ala himself, but “it was obvious that it was a 40-year-old dude trying to move his hips around like a teenage girl”, so for the final sessions, the duo turned to Kaitlyn O’Connell, who they had previously worked with on The Ningyo.

Facial motion-capture was done with a head-mounted iPhone, using iOS app MocapX, with the blendshapes for the 3D characters created by Chris Bostjanick, an artist friend of Ortega and Ma’s better known for creating the facial puppet for Thanos in Avengers: Endgame.

Since the voice actors would have had to travel nearly 10,000 miles to attend the shoot, Ortega recorded the facial performances himself, memorising dialogue phonetically, and lip-syncing to the audio recordings.

Lighting and rendering

The short was lit and rendered in Unreal Engine, using an early-access version of Unreal Engine 5.0, with Ortega and Ma placing light blockers inside the Unreal Engine level to control the position of shadows.

To provide more control over the look of the final output, the duo rendered the raw lighting effects and passes and composited them inside Unreal Engine: a real-time version of the more traditional workflow they had used on previous projects, where render passes would be generated in V-Ray and composited in Nuke.

“There are a few passes in Unreal Engine that I wish were more like V-Ray, but I’m very happy with the way it turned out,” says Ortega. “The first test renders were a huge moment for us. When we saw the characters rendered out, and breathing, we were like, ‘Oh my god. This is going to work.'”

Finishing touches

The characters’ clothing was created in Marvelous Designer, with the cloth simulations imported into Unreal Engine as Alembic caches. Other effects, like blood and dirt, were created in Houdini.

The score for the movie was created by Ortega and Ma’s friend and regular collaborator Dan Dombrowsky, while the 2D animation used for Coa’s vision sequences and to explain the culture of the Great Leopard Tribe was created by artists from Iran’s Gonbad Caboud Studio: online friends from the duo’s previous projects.

The speed and visual quality with with which animation could be previewed in Unreal Engine made it possible to develop shots iteratively, with most evolving gradually over a period of months.

Pulling off an impossible production with real-time film-making

Although 15 visual artists are credited on The Voice in the Hollow, the bulk of the work was done by Ortega and Ma themselves, who worked on the project “more than full-time” for a year.

“We worked on [The Voice in the Hollow] from sleeping to waking, seven days a week,” says Ortega. “We didn’t have one day off. The only time we weren’t working on it was when we went to Gnomon to teach.”

Despite the punishing schedule, the fact that the 10-minute short could be completed at all inside a year is a testament to the power of the real-time workflows made possible in Unreal Engine.

“If we’d tried to do this in a traditional pipeline, I just don’t think we’d have finished it,” says Ma.

“I still use V-Ray a lot, and love it,” adds Ortega. “But once you get used to the response time and the quality of the previews in Unreal Engine, it’s hard to go back.”

For Ortega as director, another major benefit of Unreal was the potential for ‘happy accidents’.

“When you re-opened a file, the camera would sometimes snap to a new location, and it would turn out to be a better camera angle,” he says. “It really felt like live action. It felt like you were walking into a set that was already built, and you were just location scouting.”

The unique look of The Voice in the Hollow

The fact that most of the work on The Voice in the Hollow was done by just two people also contributes to what is, in retrospect, one of the most compelling things about the short: its unique visual style.

Although many of the creative decisions on the project were dictated by team size – the stylised design of the characters reduced the need to finesse their facial animation, while judicious use of post-processing effects helped to camouflage any minor glitches – Ortega and Ma made a virtue out of necessity.

“The carved wood look, the film grain, the motion blur, were all not to fight against limitations,” says Ortega. “Some of the stuff that Love Death & Robots has done with Unreal is completely photorealistic, but with the resources we had, there was no way we could compete with that, so we went in the opposite direction.”

The result is an animated short that has all of the grit and dirt of the cult 1970s movies that inspired it.

Brian Pohl, Technical Program Manager of Media & Entertainment at Epic Games, and Academic Dean of the Unreal Fellowship, described The Voice in the Hollow as a “masterpiece of real-time animation”.

Speaking at the film’s premiere, Pohl singled out the film’s production and lighting design, commenting: “Working at Epic, I’ve seen a ton of material come out of the engine [including some] really beautiful pieces. “This is one of the few, if not the only one, that makes me think, ‘Was this rendered in Unreal Engine?'”

Critical reception and legacy

The Voice in the Hollow is now in the middle of its festival run, having been selected for the prestigious Seattle International Film Festival, and winning the Special Jury Award for Animation at the Florida Film Festival. This month, it won a second major Jury Award, at the SIGGRAPH Computer Animation Festival.

Although Ortega admits that he was “terrified” by the thought of how people would respond to an animation as dark as The Voice in the Hollow, it is one of the film’s darkest moments – Ala’s visceral death sequence – that has generated the strongest response at festival screenings.

“It plays the same everywhere we’ve screened the short, which is all over the world now,” he says. “It sucks the air out of the room. There is an audible gasp.”

“There’s nothing more fulfilling than that as a director. You think: ‘Oh shit, I got these people’.”

In fact, the reception for The Voice in the Hollow – a project that Ortega and Ma initially thought of as being deliberately uncommercial – has been so good that the duo’s next project is also an offbeat animated short, and is also being produced using Unreal Engine.

“I’m incredibly proud of The Voice in the Hollow,” Ortega says. “There are some things that would have been different if we’d had more time, but overall, I wouldn’t have changed anything. With The Ningyo, I was proud of the visuals, but I wasn’t super-proud of the story. With this one, I’m proud of the whole thing.”

See more of Miguel Ortega and Tran Ma’s work on their Half M.T Studios YouTube channel

Full disclosure: CG Channel is owned by Gnomon.