The extraordinary making of David Levy’s PLUG

Prometheus concept artist David Levy not only funded and directed PLUG, his debut short, but taught himself visual effects in order to finish it. Below, he tells us about the extraordinary process by which the film was made.

It’s often said that short films are labours of love. Rarely has this been truer than of PLUG, the directorial debut of concept artist David ‘vyle’ Levy. Levy not only financed and directed the 15-minute short, but even taught himself compositing and camera tracking in order to be able to complete the visual effects, working obsessively on the project for three years in between commercial work on movies like Prometheus and Ender’s Game.

PLUG premieres this weekend at a free event at Hollywood’s Gnomon School of Visual Effects, with the screening followed by a making-of session hosted by Levy and collaborators Ben Procter, Dylan Cole and Fausto De Martini, and an exhibition of the movie’s production art in the nearby Gnomon Gallery.

Levy views the short, which takes place in a world in which mankind has abandoned the Earth, leaving robots to raise the sole human survivor, as the first episode of a series – already scripted – that he hopes to make for TV.

But even in its 15-minute form, PLUG represents a remarkable testament to Levy’s persistence – and a transformative experience for its director, who describes its creation as a “discovery of the self”. In the run up to the premiere, we caught up with David Levy to discuss the extraordinary process by which the film was made.

CG Channel: How did PLUG come about?

David Levy: At a discussion a friend of mine [co-writer Hatem Benabdallah] and I had over breakfast in Venice. We were talking about doing a short film to showcase our abilities as concept artists and VFX professionals. Originally, it was just a one-minute film, but then we started expanding [the concept], and it became a script, and a script lasting 15 minutes instead of one minute – and gradually, we got more and more ambitious.

David Levy: At a discussion a friend of mine [co-writer Hatem Benabdallah] and I had over breakfast in Venice. We were talking about doing a short film to showcase our abilities as concept artists and VFX professionals. Originally, it was just a one-minute film, but then we started expanding [the concept], and it became a script, and a script lasting 15 minutes instead of one minute – and gradually, we got more and more ambitious.

CGC: Did it bear any resemblance to the final short at that stage?

DL: Yes, actually. The main character, Leila, was already there, although it was going to be a little more quirky. As we developed the script, it became something much more serious, and more realistic.

CGC: What’s the premise of the film?

DL: It’s a few years in the future. We humans have destroyed the planet. All that’s left are robots and one young woman, who was left behind. We don’t know what happened, precisely. As the film goes on, we learn more about the world: what truly happened, and why she’s the last one left.

Leila is a modern version of Tarzan. Tarzan grew up with monkeys, and they raised him. Here it’s the same, but with robots. Leila grew up surrounded by robots and that’s all she knows.

CGC: That’s something you pick up from the trailers: that the robots aren’t just emotionless machines.

DL: The whole short is a metaphor about racism. It’s Terminator if you flipped it on its head. In most movies, robots are here to destroy us. But what if humans were like the dysfunctional father of a family: like the alcoholic father of a child who is smarter than the parent, and who is going to try to tell him what he is doing wrong?

CGC: So what does that mean for Leila as someone raised by robots?

DL: That the parents she is looking for – her whole quest is to know what happened to her mother, her father, the rest of her race – aren’t necessarily the ones she’s going to find. She’s coming to realise that humans may not be what she wants them to be.

CGC: I guess that’s true of a lot of children. Their parents aren’t always what they want them to be.

DL: To be honest, maybe I’m projecting. My parents were very neglectful – it was the 1970s, they were both working very hard – and I didn’t necessarily get what I was hoping from them. I’m trying to come to terms with my own issues: trying to pardon my own parents for something I didn’t accept as a kid.

CGC: So the decision to make a film about robots isn’t just a fascination with technology?

DL: Science fiction is just a means to convey an idea: it’s a caricatured version of ourselves that is easier to digest than facing the truth directly. Robots are like a perfect version of ourselves: they’re cold, they’re emotionless, they aren’t able to abandon themselves to their emotions. In some ways, it’s an easier way to live.

I think that’s the way I wanted to be as a kid: not to have to deal with my own emotions. I thought I wasn’t going to let my emotions drive me – I was going to strive to become a good artist, a good illustrator, so that people could love me for some kind of perfection I could achieve. It isn’t a real solution.

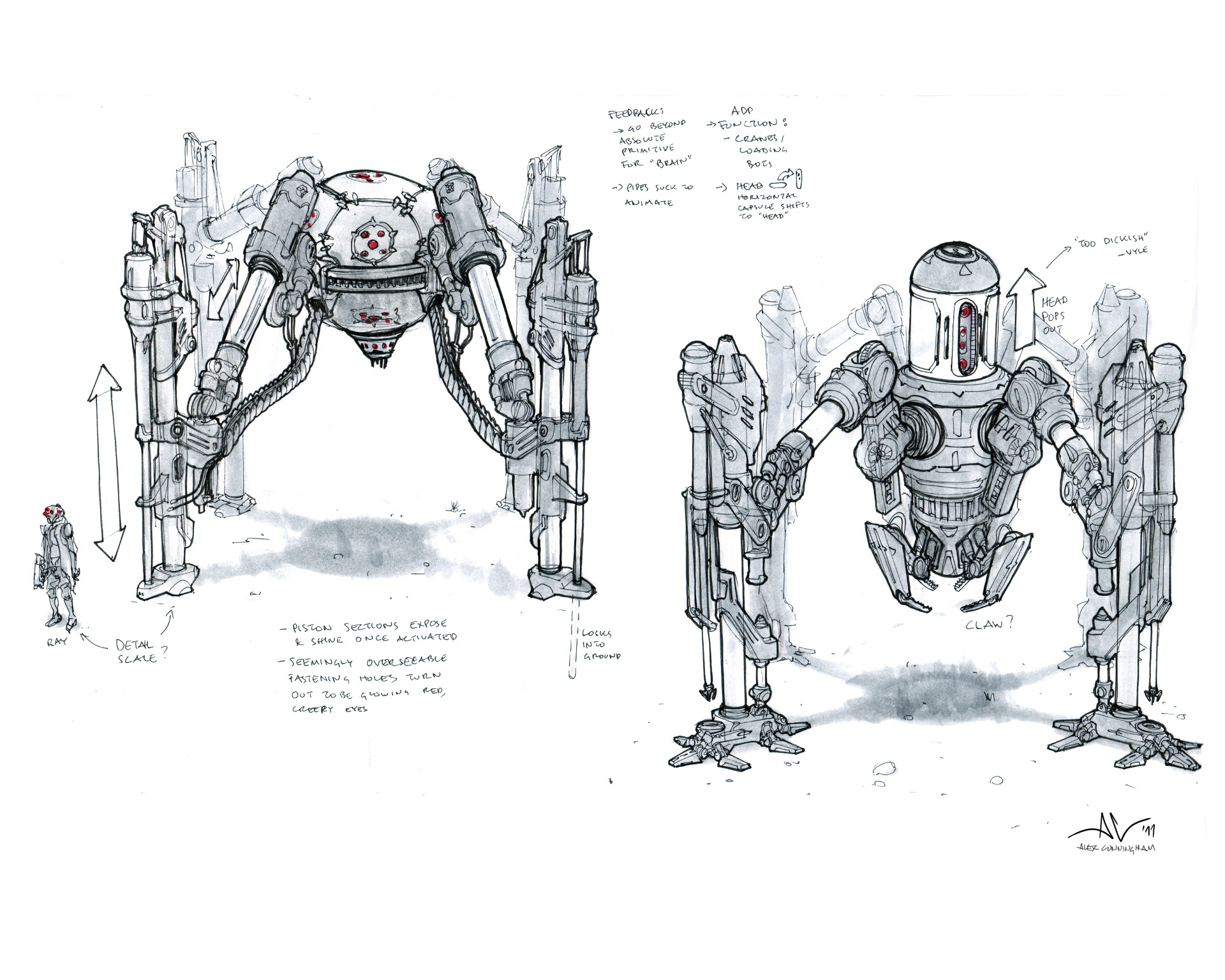

A design for PLUG created by concept artist Alex Cunningham, then studying at Art Center College of Design. Levy describes Cunningham and fellow student Lex Cassar as instrumental to the production process.

CGC: Tell us about the production. Is the movie literally shot in Portland, as it says at the start of the trailer?

DL: [Laughs] I think it would have been very difficult to find desert in Portland. We have an image of Portland as a really green area, but we turned that on its head by shooting in a desert near LA.

CGC: What was the budget?

DL: It started very low and ended much higher that I expected. I’m not going to give any numbers, but the final product was basically the price of a nice car. A car with a lot of options.

CGC: What were the unexpected costs?

DL: The main issue I faced as a first-time director was not knowing how large a crew I’d need. It was like a bell curve. By the end of the project, I was my own DP, my own VFX supervisor, my own producer to a certain extent. But in the middle – we shot for five days in a row – there were probably 15-30 people.

From the beginning, I didn’t want to hire people for free. Even if it was a much lower rate than they were used to, I didn’t want to abuse people. So at the top of the bell curve, I had to pay people, and feed them, and make sure they were comfortable while shooting in 60mph storms, and a lot of unexpected things.

Post-apocalyptic scenario: despite the scale of the work, David Levy taught himself visual effects in order to be able to complete PLUG, after original co-creator Hatem Benabdallah had to pull out of the project.

CGC: What about the post production? How many people worked on that?

DL: Ninety per cent of it was done by me. Originally Hatem was supposed to be the VFX supervisor, but he had some family issues, and couldn’t do it.

I had two choices: to give up and decide that all the money I’d spent on the shoot was a wash, or to take everything I had, with all the mistakes I’d made during shooting, and become the VFX supervisor myself.

Every day for months, I’d walk by the hard drive full of data and think: ‘I’ve got to finish.’ But at the same time, I was facing the issue of how, as a concept artist, to do the VFX. Because I had absolutely no more budget.

CGC: So you taught yourself visual effects?

DL: In screenwriting, people talk about the ‘all is lost’ moment. The moment when you’re not going to be able to face yourself as a failure. After many months of being depressed, being in a dark place, I thought: “I have no other choice but to finish what I’ve started, whatever the result may be, just so that I can face myself.”

So I went on YouTube and learned how to do compositing in After Effects, how to render in layers in 3ds Max and V-Ray. I learned tracking. And I did it shot by shot. I didn’t want to count how many shots there were on the film, because I was in despair at the thought. I just went through one shot at a time, until there were none left.

CGC: Even not counting shots, it must have felt like an impossible task.

DL: It was like sitting at the bottom of the Empire State Building, and thinking: “I’m going to have to climb that.” But because I was learning, shots that seemed impossible at the beginning became possible, and that helped.

CGC: Were you coming to the software from scratch?

DL: I was completely new to After Effects. Of course, having done 20 years of concept art, I knew how to use Photoshop, and Photoshop is a step towards After Effects, but it has quirks I hadn’t expected.

Fortunately, as time went on, I was able to save more money, so I hired Torey Alvarez, one of my friends, to do the shots I knew I couldn’t do. I learned from him. In some ways, I can composite by osmosis thanks to him.

And there were some things I knew I couldn’t learn myself, like rigging and animating a very complex robot, so I hired another of my friends, Ray Pena, who works for a small studio in Texas called Moontower.

CGC: How long did the VFX take in the end?

DL: I worked every weekend for three years – during the weeks, I was doing concept art: on Prometheus, Tomorrowland, Ender’s Game, and now Avatar 2. It was probably six months of work altogether.

CGC: And did you dare count how many shots there were when you finished?

No. I still haven’t counted. It’s probably between 100 and 200.

One of PLUG’s hundred-plus VFX shots. Levy tackled the effects one shot at a time, learning on the job – a process he describes as ‘like climbing the Empire State Building’ – and still hasn’t dared to count them.

CGC: You worked with some other well-known concept artists on the project. What did they do?

DL: Actually, they [Ben Procter, Dylan Cole and Fausto De Martini] didn’t directly work on the project. But those guys were able to save me at a moment when I thought everything was lost.

It was like at the end of a marathon where there’s only a hundred metres left but you know you aren’t going to be able to make it. I had a few shots left that were very difficult in terms of design, and I was at the end of the line.

For example, the design of the main AI entity defines the entire film. I tried so many concepts for it – I even animated it – and it just didn’t look good. At that point, I asked them: “Please help me. I just can’t do it.”

Fortunately, those guys have so much experience, and it was easy for them to be objective at a point where I just couldn’t. The last 10 per cent of the short [is down to them]. They helped me realise what was needed to finish.

CGC: So what was it like when you finally finished?

DL: Like I’d been hidden in a cave for three years. It’s a weird awakening to be back into the real world now.

CGC: Has it changed the way you tackle concept art?

DL: I think it’s changed me entirely. It’s changed the way I look at concept art, the way I look at my life, the way I look at my relationships in the world. I’m not the same person any more.

CGC: And what do you hope people take from the movie when they see it?

DL: I hope the struggles won’t be too visible, and that they enjoy it for what it is: a 15-minute short from someone who enjoys science fiction. And I hope that my message will have gotten through in some way.

PLUG premieres at the Gnomon School of Visual Effects on Saturday 25 October, after which the short will be available to view on David Levy’s website. Entry to the Gnomon event is free, and first-come, first-served.

Register for the world premiere and making-of event at the Gnomon School of Visual Effects

Read more about PLUG on David Levy’s website

Full disclosure: CG Channel is owned by the Gnomon School of Visual Effects.