Project focus: the making of Exoids

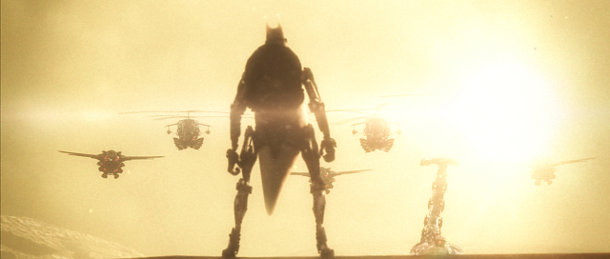

Few animations are inspired by both Rango and Mad Max. Fewer have a slug for a hero. But Exoids, created by director Aristomenis ‘Meni’ Tsirbas and an all-student crew from Gnomon Studios, isn’t your average animation. We caught up with Meni to talk mollusks, mental ray – and the continuing appeal of the animated short.

Director Aristomenis ‘Meni’ Tsirbas is used to teams of different types. Having moved to LA in 1996 to work on Titanic, he contributed to spots for Nike and Coca-Cola, acted as VFX supervisor on Star Trek: Deep Space 9 and created indie shorts Ray Tracey In Full Tilt and The Freak before directing the full-length animated feature Battle For Terra.

Director Aristomenis ‘Meni’ Tsirbas is used to teams of different types. Having moved to LA in 1996 to work on Titanic, he contributed to spots for Nike and Coca-Cola, acted as VFX supervisor on Star Trek: Deep Space 9 and created indie shorts Ray Tracey In Full Tilt and The Freak before directing the full-length animated feature Battle For Terra.

But for his latest film, Exoids, Tsirbas teamed up with perhaps his most unconventional collaborators yet. The five-minute short was crewed by students from the Gnomon School of Visual Effects, via its Gnomon Studios wing. A post-apocalyptic road movie whose stars are a hot-rodding slug and a bunch of sentient robots with a military background and a bad attitude, Exoids also marks a change in pipeline for its director.

CG Channel: This isn’t your first colloboration with Gnomon Studios. How did it all begin?

Meni Tsirbas: My friend and fellow director Shane Acker [‘9’] invited me to help with a short he was directing at the studio, called ‘Plus Minus’. It worked out so well that I was invited to stay on as the resident director.

CGC: What does your role as director in residence involve?

MT: On the production side, I write and direct the films, help create the animatics, visual effects supervise, design the pipeline, and work as part of the digital artist team as a modeler, lighter, and animator. On the administration side I manage and coordinate the productions, work with the school to recruit interns, and generally make sure everything gets done.

I also work with the good people at The Gnomon Workshop to help get the work out in the form of a Studio blog. I share producer responsibilities with Gnomon’s top brass, Alex Alvarez and Darrin Krumweide.

CGC: How different is it working with the students to working with professional artists?

MT: Well, I have the huge benefit of working with students at one of the world’s top visual effects schools, so the talent is already there. But I do recruit interns who are in later terms to ensure they’ve accumulated enough training to withstand the rigours of production.

What separates the studio from the school is that the crew here are expected to be self-sufficient, just like in a real world production. The student will learn a ton, but unlike a class environment, it’s more up to them to figure things out. Of course I’m here to supervise and to help problem-solve, but they need to pull their own weight. It’s a great challenge, and an great opportunity.

Facing up to the real world: movies like Exoids give students a chance to come to grip with the realisation that artists need to “deliver great work without friction” before they encounter it in commercial production.

CGC: How close are you to using real-world production conditions on Exoids?

MT: The main point of the studio is to give the students a real-world experience before heading out to the actual real world. So our productions are the real thing. Since the studio has a dozen workstations and smaller staff, it’s more akin to a boutique than a large VFX facility. That’s a good thing, because it teaches the students to work quickly and smartly, but still yield quality work.

CGC: So what’s the biggest eye-opener for the students about working in the real world?

The students whose eyes are opened are the ones who have yet understand that a production is results-driven with an explicit hierarchy: that artists are expected to deliver great work without friction or questioning authority. It’s a harsh lesson to learn on the job, but a great one to figure out ahead of time.

Character development art for Gus Nitrous. The idea of a world in which only slugs and robots have survived a nuclear war arose organically from Tsirbas’s attempt to combine elements students would find fun to work on.

CGC: Let’s move on to Exoids itself. How did the movie come about?

MT: Mainly from the desire to create something fun for the students to work on, so I started by combining a few of my favorite things: robots, insects, futuristic vehicles, and action. The concept was basically: ‘What would survive a nuclear war?’ That led to the notion of nomadic slugs and military robots who gained sentience and became rivals.

CGC: What influences are you drawing on for the project?

I really took to the surprising sophistication of Rango, and I’m a fan of Mad Max movies, especially [Mad Max 2] The Road Warrior. So those were the key influences. Beyond that, it was the development process. The amazing student concept team brought so many new ideas.

CGC: Mollusks aren’t the most obvious of heroes. When you pitched the idea of a cyborg slug, did anyone say: ‘You have got to be kidding?’

MT: Well, the basic idea was that the radioactive fallout advanced the evolution of the [organic] survivors, while the robots gained sentience artificially. It’s a fairly straightforward science-fiction concept. The development of slugs came a bit later, since I felt they could be designed to be more relate-able that hard-shelled insects.

What separates Exoids from most student productions is the Hollywood talent on call. This ZBrush sculpt of lead character Gus Nitrous was created by Star Trek and Avatar concept designer Neville Page.

CGC: What was the software pipeline on the movie?

MT: On the 3D side, Exoids was modeled, textured, animated and rendered in Maya and mental ray. We used ZBrush to sculpt our main character, Gus Nitrous, and modo for some of the more challenging models. Compositing was a mix of Nuke and After Effects, and editing was handled in Premiere and Final Cut Pro.

CGC: I think this is the first project I’m aware of in which you haven’t used LightWave. How come?

MT: It was a necessity because that’s what the crew knew, and since Maya has become so ubiquitous it made sense for me to use the software for more than just animation, as I did on Battle for Terra.

As for LightWave, I still love and use it because it remains the fastest and most efficient all-round 3D package out there. But modo is just a superb modeler, pretty much the best in the business.

CGC: You tested out V-Ray, too. What stopped you using it in production?

MT: V-Ray is a superb renderer, but but it wasn’t as well known by the crew as mental ray at the start of production, so we went with the safer bet. There was also the consideration that it’s strictly an indirect lighting renderer, which meant longer render times. Exoids has 100 shots that amount to almost 6,000 frames, with most needing intense motion blur. After some testing, we found that forgoing indirect lighting and rendering with traditional ray tracing in mental ray was the only way to deliver the show on time.

CGC: You were also using Maya’s built-in tools for dynamics. How well do they hold up in production?

MT: Maya Fluids are great, and generate a much more continuous and natural look than particles, but they can take an incredibly long time to simulate, cache and render. We experienced render times ranging from a few minutes to a full day. It’s insane.

One trick we’ve learned is that caching a large fluid scene can sometimes take longer than the actual render. So if you plan to render on a single machine and find that caching a fluid is maxing out your RAM and crashing Maya, just try going straight to render. It saved us on a shot featuring a full-screen explosion.

From storyboard to final shot: a series of before-and-after comparisons from Exoids.

CGC: Mimicking real camera moves and film stock is important to you. How do you achieve that effect?

MT: To me, animating a camera is as important as animating a character. When I manipulate a camera I always think of what its real-world version would be. Is it hand-held? On a tripod? Or a dolly? Then I make sure to add the imperfections like shake, bump and even an occasional error. I feel that all this familiar roughness helps better immerse the viewer into the narrative. All cameras are hand-animated and something I do personally.

One of the more unusual things we did on this show was to use in-camera motion blur, so the blur was actually calculated by Maya at render time. Normally, that takes longer to render and the limits flexibility. But our tests showed that rendering vector passes and adding blur in post really protracted the compositing process: each Maya scene would be broken into into extra elements, including discrete shadow passes, and then we’d have to devise a unique compositing solution for each shot.

However, we found that mental ray’s 2D raster motion blur only added a couple of minutes of render time per frame, and it understood transparency. In our tests, the difference between using built-in 2D motion blur and using multiple passes with vectors meant completing a shot in a day as opposed to a week. In a high-turnaround production like Exoids, that’s a huge difference.

A bright future: thanks to YouTube, the market for shorts has expanded greatly. For directors like Meni Tsirbas, they also provide a testing ground for new technologies before moving them to feature production.

CGC: Although there hasn’t been a commercial market for them for years, the Pixars and DreamWorks of the world still keep making animated shorts. Why do we all love them so much?

MT: Actually, I’d dispute the idea of there not being a market for short films. The popularity of viral videos and websites like YouTube and Vimeo have brought the format into the mainstream, and the viral film arena is something we plan to explore here at Gnomon Studios in the near future.

CGC: I was really thinking more about the revenue than the potential audience. How easy is it to make money from shorts?

MT: [My own production company’s] short films generated income from a variety of sources, with the most lucrative being film and TV option deals. Terra and The Freak were both optioned, and Terra later became a theatrical feature. The Freak was also licensed by a short film distributor, which earned us royalties for the various places they exhibited the film, such as on in-flight movies. All that started by winning awards at film festivals.

However, these days there are options that don’t require the time and expense of submitting to festivals in the hopes of someone offering you a license deal. The most direct is YouTube, where monetizing films is fairly straightforward. Just make sure to own all your content – including the music!

CGC: What relationship do they play to your own feature and live-action work?

MT: I’ll always make short films in addition to features. It gives me a chance to improve my craft and keep up with technology at a nice quick pace.

CGC: So what’s been the best thing about working on Exoids for you?

By far the best thing about this project, and with Gnomon Studios in general, is the opportunity to work with so many unbelievably talented people. These are the concept artists, modelers, texture artists, animators, and compositors that will go on to work on the world’s biggest films and games. So it’s quite the privilege.

Visit the Exoids website (Includes more behind-the-scenes material)

Full disclosure: CG Channel is owned by the Gnomon School of Visual Effects.