The making of the VFX of Wrath of the Titans

Clash of the Titans was one of the simpler pleasures of 2010. Uniting virtually the whole of London’s VFX community in its shared love of the Ray Harryhausen original, Warner Bros’ sword-and-sandals epic provided perfect popcorn-friendly holiday fare, and grossed almost $500 million worldwide. Its sequel, Wrath of the Titans, released last week, attempts to repeat the magic, re-teaming production VFX Supervisor Nick Davis with effects houses Framestore, MPC and Nvizible – and bringing in a touch of new blood in the shape of Method Studios, featured below, and The Senate Visual Effects, which contributed over 80 invisible FX shots.

The plot, such as it is

A decade after his defeat of the Kraken, Perseus (Sam Worthington) is attempting to live a quieter life as a village fisherman and the sole parent to his 10-year-old son, Helius. But Perseus cannot ignore his true calling when Hades (Ralph Fiennes) and Ares (Edgar Ramirez) make a deal with Kronos to capture Zeus (Liam Neeson). The Titans’ strength grows as Zeus’s remaining godly powers are siphoned and hell is unleashed on earth. Enlisting the help of the warrior Queen Andromeda (Rosamund Pike), Poseidon’s demigod son Agenor (Toby Kebbell), and fallen god Hephaestus (Bill Nighy), Perseus embarks on a treacherous quest into the underworld to rescue Zeus, overthrow the Titans and save mankind. You know, everyday superhero stuff.

A fresh look at mocap: former rugby star Martin Bayfield provided the basis for the Cyclops, thanks to an innovative performance capture pipeline that saw Framestore partnering specialist software developer IKinema.

Framestore’s work neatly illustrates the appeal of the Titans movies: fantastic creatures, set in equally fantastical environments. The studio completed 300 shots for the film, in two key sequences: the first, an encounter between Perseus’s group and a trio of Cyclops, and the second, the group’s assault on The Labyrinth – the towering maze which provides access to Tartarus, where Zeus is imprisoned.

“For the three Cyclops, we decided that performance capture was the only route, but that we’d play it a little differently from usual,” explains Jonathan Fawkner, the studio’s VFX Supervisor. “An initial session was recorded before the shoot to explore the behaviour of the Cyclops and inform the cast and crew. The plates for the sequence were shot in forest in Dorking, England [but instead of] mocap referenced directly in camera [we relied] on the tried-and-tested ‘tennis ball on a stick’ technique.”

“By the time we came to the actual performance capture sessions at Shepperton Studios, we had a sequence in the can, cut and camera tracked. By carefully laying out proxy trees and other obstacles [on a scan of the set] and matching the topology with a movable sloping deck, we were able to composite the Cyclops into the plate live, providing an incredibly intuitive tool.”

An innovative approach to performance capture

Former international rugby player Martin Bayfield was cast for the mocap shoot, not least because, at 6′ 10″ tall, he had something of an edge when it came to playing giants. According to Animation Supervisor Paul Chung: “Since Martin Bayfield’s performances would be used for all three, very different, Cyclops characters, I did a lot of research into how each of them might move. I wrote some biographical notes on each family member to give Martin some material to inform his performances [as] the hot-headed, muscular younger brother, his fatter older sibling who always has to rescue him from scrapes, and their dad, who both of them are a bit scared of.”

Bayfield would study the plate, the timing and the rhythm and, with Fawkner directing, attempt to hit his marks in each shot. The team would try as many variations as time would allow, and the various takes were delivered to the client to pore over and make selects from within hours of the capture, ready for editing in the normal fashion. According to Fawkner: “The massive benefit of doing the capture this way was that the animation was effectively blocked and locked very early on, leaving more time to finesse the details.”

To minimise loss of detail in the movements captured – and thereby avoid a stereotypically ‘mocapped’ feel to the results – Framestore developed a new pipeline, using several witness cameras to complement the capture input. The studio partnered UK-based software developer IKinema to create tools to help quality control the solving process, comparing the solve to witness cam footage.

According to Nico Scapel, Framestore’s Head of Rigging: “The real challenge is to get the most accurate and truthful reproduction of the actors’ motion. By overlaying IKinema’s solver with calibrated witness camera footage, we could check how well the solver matched the actors’ movement.”

Compared to more rigid traditional methods, the software gave the Framestore team creative control earlier in the pipeline and, crucially, enabled the artists to fine tune the results more freely.

“The key to great mocap is how you give it to Animation,” says Scapel. “Many studios have a mocap department which has a large motion-editing team, and they fiddle with the data [before] it goes to Animation, who are often less than thrilled with what they get. We wanted to give the animators [something] as close as possible to the raw performance and let them work it up from there.”

New approaches to rigging

Scapel’s rigging team (Leads Laurie Brugger and Matthew Goutte, and Rigger Mauro Giacomazzo) had worked together on Dobby and Kreacher in the final Harry Potter films, but this was a whole new level of intensity. “We soon realised that these creatures were much more dynamic, and that anatomically there was lots more to do,” recalls Scapel. “We ended up with about 10 times the amount of data that we generated for Potter. Our hero mesh was about a million polygons, and [each of the 50-odd maps] that we used was the equivalent of a 900 megapixel image. We also had four months fewer than we did for Potter.”

Anatomy guru Scott Eaton worked with the team for much of the project, creating detailed sculpts of all three characters and inverse meshes that represented their internal anatomies. The rigging team then provided the animators with controls enabling them to adjust the muscle tension.

The resulting rig had a high level of detail, but no secondary dynamics, so the creature FX team would run a simulation of the Cyclops’ fat and muscles jiggling and the skin sliding. To achieve these movements, they extended the approach they had used on Dobby and Kreacher: essentially, to have a volume mesh providing a certain thickness under the skin, rather than doing a typical surface simulation.

“We worked hard to ensure that, on the shading and rendering side, we anchored the displacement of the mesh with the movement of the skin, so that [the result] doesn’t look like a series of surface events; that the Cyclops has internal organs, bones and muscles,” says CG Supervisor Mark Wilson.

Since the brow line and area between the eyes normally provide so many emotional cues, Framestore had to develop a rig for the Cyclops’ faces that could function as a left eye, a right eye, or a hybrid of both.

The creatures’ faces posed many of the biggest challenges. The one part of the Cyclops animated purely by hand, they were designed to be appealing, but not cartoony. Since so many key emotional cues, such as the brow line and surrounding wrinkles, typically require two eyes, the Framestore team created a large central eye with two modified tear ducts and a highly flexible brow that could be treated either as a left or right eye feature, or as a hybrid of the two. Wrinkles were generated automatically according to the degree to which the skin was stretched or compressed: a system Framestore also used for the creatures’ hands.

Raytracing with RenderMan and Arnold Renderer

The release of RenderMan 16 midway through production meant that Wrath of the Titans marked a departure from Framestore’s previous lighting workflow. “From the outset, I wanted to push what has been termed ‘physically plausible lighting’, if not perfectly physically realistic lighting,” says Fawkner. “RenderMan 16 allowed us to raytrace the whole character, the weapons and the interactive effects. [Being able to match real lights more accurately] made for a deeply rewarding result in a way that doesn’t compare with a more traditional RenderMan pipeline.” The studio also retooled its skin and hair pipelines to optimise them for raytraced global illumination.

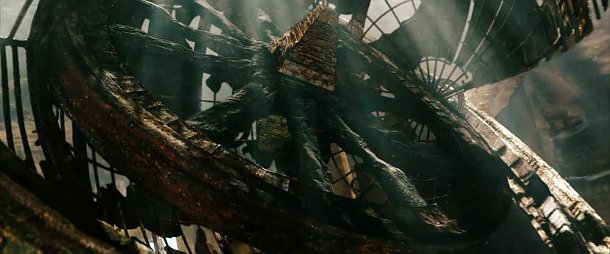

Framestore’s physically plausible lighting workflow was extended to the studio’s second key effects challenge. First seen by Perseus and his men from a distance, the Labyrinth is an impossibly tall tower, with circular layers in constant revolution, grinding at each other as they rotate in opposite directions. After gaining entry, the heroes are separated inside the cavernous interior until Perseus fights and defeats the Minotaur, whereupon the entire interior realigns itself and a gateway to Tartarus appears.

“We usually body tracked the actors and placed CG dummies in situ,” says Fawkner. “When they were lit correctly and looked like the guy on the plate, you knew you were in a good place. I wanted to bring volumetric lighting into the picture, too, as a complement to the physical lighting I’d already got in place. We were using [SolidAngle’s] Arnold Renderer for the sequence, which chews through geometry like nobody’s business.”

The team’s commitment to realism even extended to bringing in the movie’s Gaffer to explain how he had lit the live set, and how he would have liked to light its virtual equivalent. “It brought a welcome element of realism and practicality, but it was also creatively really rewarding,” says Fawkner.

The Labyrinth also posed a challenge for Nvizage, which used its OptiTrack mocap set-up for previsualisation. Nvizage’s sister effects company Nvizible provided the 83-second stereo CG shot of the Armillary Sphere (above), which contains a mechanised representation of the earth that breaks open like an orange.

But the Labyrinth was already posing a challenge before long before the final assets were created. To help plan the complex sequence, in which the motion of the walls constantly increases and decreases the space around the actors, the film-makers called in previz house Nvizage, fresh from its VES Award-winning work on Hugo.

Although Nvizage had previously used its own proprietary system, it wanted a more intuitive set-up for Wrath of the Titans, installing a 16-camera OptiTrack mocap system and its corresponding visualisation software, ARENA, at Shepperton Studios. Another key factor in its choice of hardware was OptiTrack’s virtual camera system, the Insight VCS, which it used to choreograph the Perseus’s fights with the Cyclops and Chimera.

?The Insight VCS was perfect for combat sequences,? said Nvizage co-founder and previs supervisor Martin Chamney. ?It’s great at that kind of visceral, fast-paced, handheld camera work.”

The Chimera attack itself was one of the 280 shots completed by the team at MPC, led by VFX Supervisor Gary Brozenich. The Chimera itself was largely designed in pre-production, with concepts then passed to MPC who recreated them as a CG model. The key challenge for the rigging and animation teams was to make a beast with two heads move realistically, an issue addressed early on through a range of motion studies.

According to Brozenich: “The trickiest issues involved where to place the split in the neck – how far back on his spine would feel natural, and how to proportion the rest of the anatomy to compensate. We also had to handle the interpenetration issues arising from two heavily mobile portions occupying the same anatomical space.”

The completed animation references material of lions hunting and attacking, while the Chimera’s fiery breath used elements created using Maya and Flowline, combined with actual flamethrower material shot on set.

Early designs for Kronos ranged from a fully elemental creature to a more human-like giant. MPC used a combination of tools to simulate the lava, including Flowline and PAPI, the studio’s rigid-body solver.

In addition to the Chimera, MPC created the Makhai – two-headed sword-wielding demons that emerge from the rock surrounding Kronos – and Kronos himself. The studio experiemented with different designs for the the fearsome king of the Titans, from a completely elemental creature to the eventual more human-like giant, shooting reference of clay mixtures painted onto the face and body of an actor to help the modelling team visualise the look necessary, and to capture accurate crack and displacement maps.

As Kronos is an FX-driven creature, MPC’s team was also faced with the huge challenge of creating behavioral effects elements such as the two dense plumes of smoke that trail behind him. Scanline’s Flowline was used to simulate the smoke simulations, augmented with live-action elements. In order to handle the huge amount of data per frame, a new set of volume tools was created.

In addition to the smoke plumes, Kronos oozes and sprays different forms of lava from his surface. For the liquid magma, MPC’s artists used Flowline fluid particle simulations, while the solid rock was simulated using MPC’s proprietary rigid-body solver, PAPI. Kali, MPC’s finite element based destruction tool, was used to handle the cracking and the breaking of rocks, trailing particles and to create fluid dust simulations and particles.

Method Studios handled the 114-shot sequence showing the awakening of Kronos, and the surrounding environment. You can find a breakdown movie on the studio’s website.

The visual effects on the Kronos sequence also included 114 shots created by Method Studios, featuring a fully CG Kronos in an entirely CG environment. The action takes place in a huge collapsing chamber, with Perseus and Andromeda freeing Zeus as Kronos awakes. Digital doubles of leading actors were created and composited into scenes along with fire, smoke, explosions and flowing lava. For the Underworld establishment sequence, Method London’s challenge was to get across the massive scale of the CG environment which included detailed matte paintings and the creation of a stone pillar tower which Zeus is later bound to. In this VFX-heavy scene, Zeus, played by Liam Neeson, is drained of his powers as fiery lava bleeds from his arms and flows into the surrounding rocks to give Kronos strength.

The sequence illustrates the complex interplay of effects typical of Wrath of the Titans: both between creatures and environments, and between the studios collaborating on the project.

“There were many challenges on this one,” says Method’s VFX Supervisor, Olivier Dumont. “It was a fluid production pipeline, not only between our teams, but with the entire production. Our ideas and designs for effects and character animation were welcomed, which made it a gratifying and inspiring process.”

Wrath of the Titans is currently screening at cinemas worldwide. At the time of posting, it was topping box office charts outside the US, holding off even the 3D remake of Titanic.

Visit the official Wrath of the Titans website

Acknowledgements and useful links

This story makes use of material put together by the following companies:

Framestore

IKinema

Method Studios

MPC

You can also read more detailed explorations of Method Studios’ work in the articles on CGSociety and AWN. The Art of VFX has a detailed Q&A with Olivier Dumont, which focuses mainly on Wrath of the Titans.