Q&A: Titanfall lead artist Joel Emslie

In the run up to the Art of Titanfall show at Hollywood’s Gnomon Gallery, Respawn Entertainment’s lead artist discusses the concept art workflow for the game, kitbashing bitchin’ maquettes, and his tips for young artists.

A games industry veteran with two decades of experience, Joel Emslie has worked as a senior or lead artist at Ronin Entertainment, Namco Bandai Games America and Infinity Ward, on projects including Armor Command, Legend of the Blade Masters, Kill Switch, and the Call of Duty and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare series.

A games industry veteran with two decades of experience, Joel Emslie has worked as a senior or lead artist at Ronin Entertainment, Namco Bandai Games America and Infinity Ward, on projects including Armor Command, Legend of the Blade Masters, Kill Switch, and the Call of Duty and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare series.

He is currently lead artist at Respawn Entertainment, where he worked on online multiplayer first-person shooter Titanfall, in which players can commandeer Titans – giant mech-style exoskeletons.

Over 90 pieces of artwork from the game, including characters, weapons, spacecraft, environment – and of course, the Titans themselves – will go on show at The Art of Titanfall, a free exhibition at Hollywood’s Gnomon Gallery, from 3 May to 3 July. We caught up with Joel to find out what visitors can expect, the game’s concept art process – including kitbashing 1:6 scale maquettes of the mechs – and his advice to young artists.

CG Channel: There’s already a pretty detailed 192-page book on the art of Titanfall. Will people who’ve read it find anything new in the Gnomon Gallery show?

Joel Emslie: There are many pieces featured in the Gnomon show that aren’t in the art book. We went out of our way to collect some art that people could see for the first time. My own personal touch on the show is the maquettes. They aren’t very photogenic, but they look bitchin’ in person.

CGC: We’ll get to those later. But first, how long a project was Titanfall?

JE: I’ve been with Respawn and on Titanfall from day one. Some of the core elements for the game started taking shape in December 2011, but I don’t think we even had a title until April 2013.

CGC: What size team did you have on the project?

JE: Our entire art department during the production of Titanfall was just under 20. At times we had an additional group of up to four concept artists to help out. There were many periods where the entire art department was focused on conceptual design work using various media, including 2D, 3D, and practical model-making.

In total, we created around a thousand individual designs, or just over. The concepts range from thumbnails to full-colour production paintings.

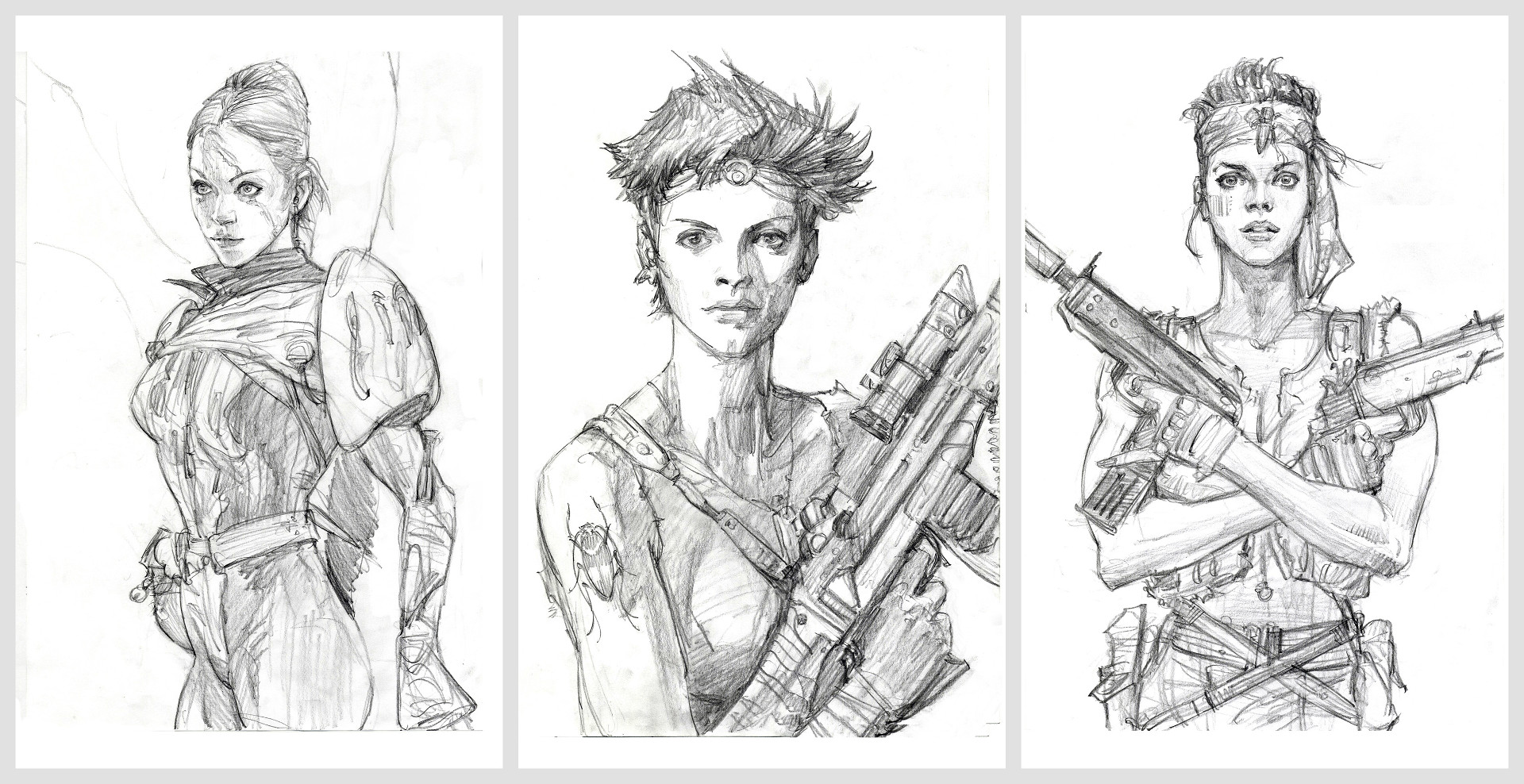

An early sketch of a militia soldier, drawn by legendary Star Wars and Harry Potter concept artist Iain McCaig. An old friend of Emslie’s, McCaig worked on character designs for Titanfall early in the project.

CGC: The credits for the Gnomon show namecheck a pretty impressive list of independent artists. How did you divide up work with the in-house staff?

JE: We were very fortunate to have so many top-tier concept artists on our project. The division of work was based on what we needed at the time and the different strengths of the individual artists. We always maintain a ‘for the good of the project’ mentality towards how we conceptualise and execute on assets.

We brought on Iain McCaig early on in the process. He’s an old friend of mine and I saw the opportunity to have him come in and riff on some character designs. He had some downtime in his schedule so he came in and cranked out some really awesome concepts. His work has so much personality and even though it was early on in the project a lot of the spirit of what we worked on together in those early days lived on into completed game.

CGC: Is there a ‘typical’ workflow for concept art at Respawn?

JE: Our conceptual workflow is pretty standard, but it has to be adaptive. We start with an idea, and flush it out in 2D, 3D or plastic and refine from there. We place a lot of emphasis on the end result, rather than the processes that take us there. In the end all that matters is what’s in camera and in the game.

Our environments are usually blocked out by geo designers, followed by a meeting with the environment art team. This process continues into several paint-overs if necessary. Sometimes the set extension of the level will direct the look and lighting of the environment. As far as characters and mechanics go, sometimes we would create 2D concepts and other times I would create plastic maquettes.

A maquette of an Atlas-class Titan with a human figure for scale. The model was created through a mixture of scratch building and kitbashing, assembling parts from hobbyist stores over a custom wire armature.

CGC: And very impressive the maquettes look, too. Why did you decide to create physical models?

JE: We did piles of mech designs early on in the project, but I realised that no matter how awesome our paintings were, the idea just wasn’t gelling with the rest of the company. If we wanted to sell these things we would have to find another way.

I sculpt in my spare time as a hobby and I have always liked making plastic models, so I started thinking about how I could use my hobbies on the project. I realised that I couldn’t sculpt the models because that would take too long, so I started looking at ILM’s work on Star Wars and how quickly they had to build those models. Kitbashing and scratch building seemed like the way to go.

I did my first kitbash on the project in October 2010. The response was strong from the entire company. The first maquette was pretty rudimentary, but my techniques and speed improved with each new maquette.

CGC: How many did you create?

JE: I ended up doing two Titan maquettes. This first one was the Ogre, a kitbash; and the second the Atlas, a scratch build with some kitbash thrown in there. I didn’t have enough time left in the project to do a maquette version of the Stryder, so that Titan was created in a more standard way. I created other maquettes for character and weapon design as the project progressed.

CGC: Can you describe the process?

JE: First, I avoid 3D printing. Everyone asks about 3D printers but I’ve opted for a desktop vacuform machine instead. I don’t feel disciplined enough with the process to incorporate a 3D printer yet: one of its strengths is the way physical restrictions guide the look of the art.

I start off with an end goal in mind and go into reference collection mode, finding parts from hobby stores and hardware shops, and bringing them back to the office. There are countless online stores that carry loose parts for all kinds of 1:6 scale dolls, especially military-themed ones. They vary in quality but they’re really detailed. I take these parts and modify them to a point where they look like something new.

If it’s a human-like character I start with a basic 1:6 scale figure as an under structure; if it’s something like a Titan, I build a wire armature and build on top of that. Once I have an under structure, I work in layers using materials ranging from rubber sheeting to hard foam or balsa wood. I surround myself with piles of parts and chase down ideas by gluing, cutting, Dremeling and grinding, then spray-paint the end result with white primer.

This process is a throwback to how many of the props and costumes on movies like Star Wars and Blade Runner were made. I’m just doing it on in a 1:6 scale.

The strength of this process is that at its core it uses parts that are meant to be authentic, which have an automatic grounding effect on the design. Plus, there’s nothing more awesome than plopping a maquette on an artist’s desk on a little Lazy Susan and saying, ‘Build that and put it in the game.’

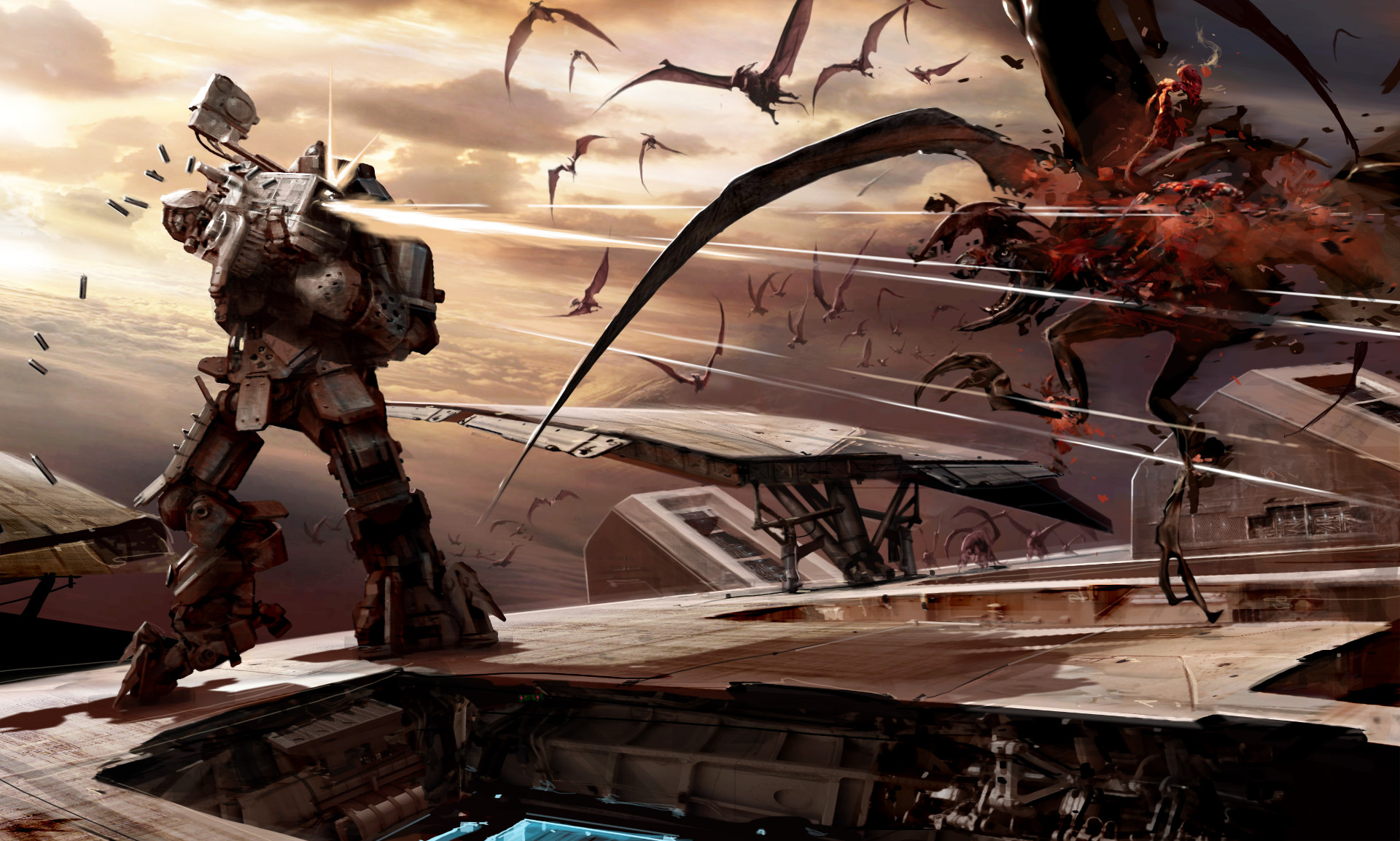

An image created by Matt Codd. Although the brief for Titanfall evolved during development, constant themes were a visual style grounded in reality, and a ‘David versus Goliath’ sense of scale in the combat.

CGC: The original brief for the game seems to have been fairly loose. What kinds of design ideas were you turning over during the exploration phase?

JE: We were all over the place. For a while, we were very creature-focused. Then we went with creatures and robotics. The one thing that never changed from the very beginning is that we were working towards a very authentic grounded look for the art.

That was something that we could always agree on, no matter how crazy the ideas were. One of our early concepts showed an apocalyptic soldier firing an RPG at a flying dragon. You can see that same thing playing out in the final game, only it’s a sci-fi pilot firing a rocket at a 20-foot-tall mechanised Titan. Maybe one theme has always been David versus Goliath!

CGC: How did the scale of the Titans change over time?

JE: The most memorable change we made was the original kitbash of the Ogre, which was meant to be a dive suit for a human. We were screwing around with the maquette and put an action figure next to it. Suddenly the human-sized suit was now 20 feet tall. It was a defining moment in the direction of the game.

After that, we had to lock in the scale pretty early because we had to set metrics in order to build the world.

CGC: Did you try consciously to differentiate Titanfall from other mech-based games?

JE: The conscious effort was how the Titans moved and played. We didn’t set out to create a robot sim. We aimed to created a robot that controlled like a natural extension of the player’s body. Our goal in the art department was that the Titan designs would support gameplay in the most believable way possible.

CGC: Did you go as far as specifying how a Titan should move in the concepts?

JE: We left all the functionality to our animation and design departments. Many modifications were made to the designs to make sure they moved in the way the animators and designers wanted.

A concept by Brad Allen, showing a squad of IMC Spectres on patrol. Good concept art isn’t just attractively rendered, advises Joel: it’s crucial that the design underlying the image is solid, too.

CGC: Let’s round up with some careers advice. What three things do you most look for when hiring new artists?

JE: Creativity, understanding of composition, and taste.

CGC: What skill do you find most under-represented in people applying for jobs?

JE: An emphasis on draftsmanship. As a 3D model maker, I sometimes find it challenging when I’m presented with a concept which is heavily photobashed. This stuff looks gorgeous, but it’s really difficult to translate what you’re looking at.

CGC: And what’s the most common mistake young concept artists make?

JE: A long time ago, someone told me that a concept I created was only good because of the way I rendered it. The fundamental design wasn’t solid. I think it’s possible for the newer concept artists out there to get caught up in rendering techniques and not focus on the core design.

The Art of Titanfall is on show at the Gnomon Gallery in Hollywood, CA from 3 May to 3 July. Entry is free.

Find more information about The Art of Titanfall exhibition on the Gnomon Gallery website

(Includes opening times, directions and a full list of participating artists)

Full disclosure: CG Channel is owned by the Gnomon School of Visual Effects.