fmx 2011: Tuesday’s news

In the first of our reports from Europe’s premier CG festival, Jim Thacker braves the crowds to discover the magic of ILM, the future of production lighting pipelines, and why Moore’s Law won’t fix all of our rendering problems

For some years now, fmx has been Europe’s premier CG industry show. But with over 15,000 people expected through the doors of Stuttgart’s elegant Haus der Wirtschaft over the course of the coming week, Germany’s answer to Siggraph just got a whole lot bigger.

With huge helium balloons in the plaza outside announcing that the show has now spilled over into a second venue, crowds gathered in the Gewerkschaftshaus’s stereo screening theater to watch a two-hour retrospective on the magic of ILM, and presentations on some of the year’s most striking movie projects, including Pixomondo’s work on Sucker Punch and a packed session on Uncharted Territory’s VFX for Anonymous.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOga2Mf8KQITV documentary Industrial Light & Magic: Creating the Impossible formed the starting point for a two-hour retrospective and panel discussion of the legendary visual effects studio’s work.

Back in the main venue, fmx’s technical programmes were also benefiting from the extra space. With the sessions on rendering pipelines moving to the original venue’s biggest theater, the chunky modernist chandeliers of the König-Karl-Halle seemed a suitable backdrop against which to discuss production lighting.

The Bakery was up first, demonstrating the company’s all-in-one relighting solution, Bakery Relight: in particular, the intelligent caching system used to maximise speed of on-screen updates when a lighting change is made, and the point cloud format in which scene information is baked – in reality, more of a ‘disc cloud’, given that the points also have radius and orientation.

We caught up with company co-founder and DreamWorks veteran Erwan Maigret in the run-up to the show to discuss the software in more detail. You can read that interview here.

The move to all-raytrace pipelines

Rounding off the first morning, Solid Angle founder Marcos Fajardo hosted a packed session on the development of Arnold: the cult Softimage-compatible raytrace renderer used at Sony Pictures Imageworks since 2006’s Monster House.

Over the course of 40 minutes, Fajardo debunked many of the myths surrounding all-raytrace rendering pipelines – chiefly, that they’re too slow - pointing out that the time saved in not having to fake or finesse effects like deformation motion blur can outweigh raw render speed.

“It’s not so important that your final renders are taking hours per frame: you can put a lot of machine in the renderfarm, and that’s cool,” he said. “Your main [cost] is artists’ time.”

Nostalgia ahoy: raytrace pioneer Marcos Fajardo singles out this image as the pivotal factor in his decision to work in CG

Having showed a 400-million-polygon asset from G-Force as proof that even the heaviest scenes can be raytraced in production, Fajardo singled out volumetrics as a particular area of benefit.

“[With a traditional hybrid Reyes renderer] you’re losing the interaction of the raytrace effects with the volumes so even simple things like shadows become a problem,” he said. “[With Arnold] it just works. There’s no ‘gotcha’.”

His collaborator, SPI’s principal software engineer Larry Gritz – himself the prime mover on render engines from BMRT to Gelato – echoed Fajardo’s sentiment that raytracing was the future of production rendering, before going on to discuss Open Shading Language.

Rather than calculate surface colours on scene geometry, the language is used to calculate ‘closures’, which can then be passed back to the renderer for further processing.

SPI estimates that use of OSL – developed at the studio, but now an open standard – has increased throughput on its upcoming movies such as The Amazing Spider-Man and Men in Black 3 by 20 per cent.

Gritz also discussed the increasing importance of “thinking in a material-centric way” during production, via the adoption of new techniques such as Multiple Importance Sampling.

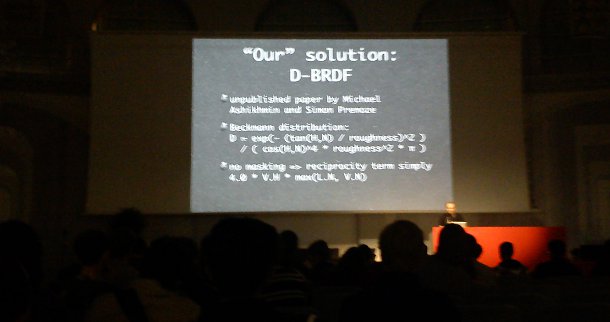

The physically based rendering sessions take a sudden upwards turn in technical complexity. Note the shaky hands.

The process samples a material’s BSDF function to determine the most important directions in which a surface will react to light. By combining this information with standard light sampling, MIS can reduce render noise without increasing sample count.

Hollywood switches to physically based materials

The shift towards the use of physically based materials in production was also a topic picked up in the day’s two-hour closing panel session, which brought together senior staff from Disney, Blue Sky, Pixar and ILM.

With Disney’s Mohit Kallianpur confirming that the studio has moved to a full physically based pipeline for its next show, most of Hollywood’s leading facilities are now using what would once have been considered an unacceptably time-intensive (although unarguably realistic) workflow in production.

Echoing Marcos Fajardo’s point that the most important cost in production these days is not processing time but artists’ time, the panel commented that the shift was intended to make the production process more straightforward for lighters.

“For us, that was one of the reasons we put it into place [at ILM],” commented Tim Alexander, VFX supervisor on Rango. “It was to make our renders better, but also to create them in a way that made sense; that was more like lighting [a real film] set.”

Although the number of lights and shader controls used in a typical shot varied dramatically from studio to studio, all of the panel members felt that the shift to physically based workflow reduced the ‘mental complexity’ of the process, collapsing scores of hard-to-grasp controls into a small set of intuitive, real-world properties.

“It’s much easier for the artists,” commented Kallianpur. “They don’t have to worry about coefficients of absorption or indices of refraction any more.”

Other current trends identified by the panel included the co-option of live-action cinematographers into CG work - legendary Coen brothers collaborator Roger Deakins was called in to advise on Rango – and the growing need to achieve near-final-quality lighting at the layout stage, in order to minimise the need for costly revisions later in production.

Why Moore’s Law won’t save us

But technology will not solve all our woes. Asked if he thought that Moore’s Law – the tendency of hardware to double in processing power every two years – would eventually remove all time pressures from production, SPI’s Larry Gritz responded:

“It would be thrilling if all our frames could take six hours, but we’re not even close. I’ve asked at all the places [I deal with] and average render times are getting longer. If anyone thinks real-time [production rendering] is around the corner, they aren’t looking at the trends.”

Tim Alexander agreed, observing wryly: “If you can render everything in real time, maybe you aren’t putting enough on screen.”

Ultimately, it seems that artists are their own worst enemies, with modellers and texture painters taking advantage of modern hardware to cram beautiful but unnecessary detail into their work – with disastrous consequences for those further down the pipeline.

As Blue Sky Studios’ Andrew Beddini, the head of lighting on the last Ice Age movie, put it: “We’ve found that the thing to do is not to give artists the best machines, especially at the front end of the pipeline. Give a modeller a machine five or six years old, and [I guarantee] it’s going to have a positive impact when you get to the back end.”

View more highlights from fmx 2011 on the show website (includes live webstreams of some sessions)