Weeds: the story of an indie short made by Disney artists

Discover how a team of Disney artists working in their personal time created a touching animated short about the immigrant experience using the same tools and workflows as the studio’s animated features.

Weeds, Kevin Hudson’s beautiful three-minute short, is an unusual project on many levels. It’s a story about the human immigrant experience told through a cast of non-human – and non-speaking – characters. It’s an Oscar-qualifying animation that is available to watch online, at least until the end of the month. And perhaps most unusual of all, it’s an independent short film created by a team of artists with day jobs at Walt Disney Animation Studios, using the same tools and techniques as they do on the company’s animated features.

The immmigrant experience, retold through a cast of plants

For a film with a big theme, Weeds is set on a small canvas. The entire short takes place in two suburban front yards: one lush and well-watered, the other parched and dry. Seeing his fellow dandelions withering in the heat, the protagonist – unnamed in the film, but referred to by his creators as ‘Dan’ – uproots himself from his barren birthplace and begins the journey to a new life in the neighbouring yard.

To get there, he must cross the driveway separating the two houses. It’s only ten feet of hot concrete, but to a fragile little weed like Dan, it might as well be an entire desert.

The origins of the story

The idea of making a short film about the immigrant experience occurred to Kevin Hudson during his own period of immigrant life: the years he spent working as an asset lead at Double Negative’s London studio.

“Everybody [in the UK] was great, but it was a precarious place to be,” he says. “If I’d quit my job, I would have had 30 days to vacate the country. It made me imagine what it must be like to come to a country where you don’t speak the primary language, or where there may be displeasure at you being there.”

“Coming back [to the US], there was so much anti-immigrant and anti-refugee rhetoric floating around that it didn’t sit well with me,” he adds. “I had the feeling that I had to say something, or I was going to explode.”

A death in the family. The idea of using dandelions as metaphors for human refugees occurred to director Kevin Hudson while contemplating his elderly neighbour’s similarly parched front yard.

The idea of using plants as a metaphor for human refugees came to Hudson by chance while gardening.

“I was pulling out the weeds and I looked over to my neighbour’s yard,” he says. “She’s elderly and never waters it, so everything is dead, except for a few dandelions clinging to the edges of the sidewalk. I looked over and thought, ‘No wonder the dandelions keep coming to my yard. If I was over there, I’d want to be here too.’ It was a moment of inspiration.”

“Some plants we deem to be flowers; others we relegate to being weeds,” Hudson continues. “But plants are just plants. They’re all beautiful in their own ways.”

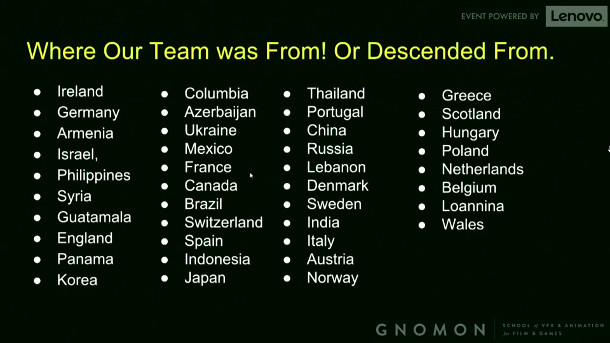

The geographic origins of the 55 artists who worked on Weeds. For many of the team, which included several first- and second-generation US immigrants, the short had an acutely personal resonance.

An international team for an international theme

Hudson was fortunate to be working in the perfect place to make a film with an international theme. As a leading feature animation studio, Disney recruits staff from all over the world. Hudson calculates that the 55 artists who worked on Weeds were born in, or had ancestors who were born in, 40 separate countries.

For some of the team, the short had a deeply personal resonance. As Hudson recalls, “One of the first animators who came on to the project [looked at Dan and] said: ‘That character’s me. My parents brought me to America for a better life.’”

Disney also has an internal program enabling staff to use company facilities to work on their own projects, providing that all of the work is done in their free time. As a result, Weeds was created using the same software as many of the studio’s animated features: Maya for modelling and animation, Houdini for effects, proprietary tools Paint 3D for 3D painting and Hyperion for rendering, and Nuke for compositing.

“The nice thing was that we had all of the glue that holds the pipeline together,” says Hudson. “When you’re doing something in your spare time, not to have to work on the pipeline is a saving grace.”

Because the project was being created using in-house software, Hudson could only recruit Disney artists to work on it, rather than calling on friends at other studios. “That was a blessing and a challenge,” he says. “I had access to all of these amazingly talented people, but if those people were busy, nothing progressed.”

All told, it would take 18 months to complete Weeds’ 30 shots, with individual artists contributing anywhere between a day and several weeks of their time, all fitted in around work on Disney’s commercial features.

The fact that Weeds was being created within Disney’s facilities also set a high – albeit self-imposed – benchmark of quality for an unfunded, independent short.

“I love Disney,” says Hudson. “I grew up next door to Disneyland; I think it’s an awesome company. I didn’t want to do anything that Disney would be less than 100% proud of.”

The set of Weeds. Colour and lighting cues, building design and a host of subtle little details create contrast between Dan’s unpromising homeland on the left, and the earthly paradise to which he hopes to escape.

Environment design

Hudson created the set of Weeds himself, bouncing ideas off art director Jim Finn. Although small by movie standards, the set embodies Disney’s presiding design principle that every detail should be there by intent.

The house where Dan starts his journey has a Southwestern or Middle Eastern design; the one he hopes to reach has a European design with a mansard roof. The wave patterns on the concrete driveway and the foot of the garage door reference the seas – the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, the Straits of Florida – that human refugees have had to cross in history. Even the arm of the lamp above the door echoes the Statue of Liberty: a reminder of neighbouring Ellis Island, gateway for over 12 million immigrants to the United States.

The ‘Tujunga direction’: the urban sprawl from which Dan hopes to escape, represented by a matte painting in the background. An 80mm lens was used to flatten the perspective, creating a sense of claustrophobia.

The set design also contains a couple of nice Disney in-jokes. The urban sprawl seen in the background of some shots was nicknamed ‘the Tujunga direction’ after one of the company’s less glamorous temporary office spaces. (The name also appears in one of Disney’s own Easter eggs, popping up on a street sign in Zootopia.) By contrast, the green suburban wonderland opposite is ‘Spielbergland’.

Despite his non-human proportions, Dan is able to ‘act’ convincingly during the short, with his leaves alternately reading as arms or a backpack in silhouette. The leaf in front of his ‘chest’ helps convey emotion.

Character design

Hudson was also responsible for modelling Dan himself, facing an interesting problem in character design. On one hand, Dan had to be a real plant; on the other, he had to be capable of conveying human emotions.

“Since [Dan has] no facial characteristics, his body language had to tell the complete story about what he was feeling,” Hudson says. “This needed to be a character that we could see thinking; that could have dreams for what he wanted to do with his life.”

The final design balances these two competing needs. Although Dan’s leaves emerge from the base of his stem, they curve to read as arms in silhouette. A back leaf stands in for a backpack; a chest leaf helps to convey emotion. In the scenes after Dan unearths himself, a forked root stands in for legs.

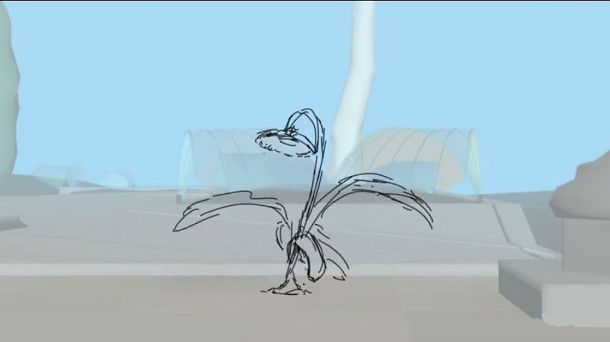

Director Kevin Hudson acts out the part of Dan the dandelion as layout artist Jean-Christophe Poulain films from the top of a stepladder. The footage was used to help plan the animatic for the short.

Layout and animatic

With the base assets complete, Hudson enlisted Disney layout supervisor Jean-Christophe Poulain to help turn Weeds from a generalised concept into a working animatic. Since there was no dialogue to guide the process, Poulain shot cameraphone footage of Hudson acting out the role of Dan. When Poulain’s layout was edited together with a temporary score, the impact was immediate.

“Suddenly we had a working movie,” recalls Hudson. “It was a great tool for showing people that we were serious about making Weeds. [As a first-time director] one of the toughest things is convincing people that it’s worth them spending their time helping you.”

One of the people Hudson convinced that he was serious was Disney associate producer Brad Simonsen, with whom he had worked on Big Hero 6 and Zootopia. Simonsen was to play a pivotal role in attracting other artists to the project, notably animation supervisor Hyun-min Lee.

“With an [independent short], the studio doesn’t help you find people,” points out Simonsen. “When you’re working on a feature, you can go to artist managers who run departments and can tell you who’s available. On a project like this, they say, ‘Sorry, you gotta recruit yourself.”

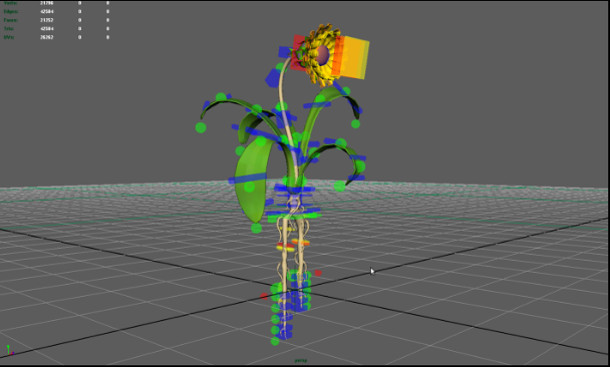

Dan the dandelion’s animation rig. His roots use a conventional IK foot setup, while his leaves and stem are five-joint spline IK chains. Each of his facial ‘petals’ can be posed individually to help convey emotion.

Character rigging

Dan’s animation rig was created by character TD Joy Johnson, winner of a VES Award for her work on Elsa in Frozen. Dan is a character of a completely different type. His ‘feet’ use a comparatively traditional IK rig, but the ‘arms’ all have five points of spline IK, with no equivalent for a hand. His ‘face’ is made up of two whorls of ray florets and two of sepals, each of which can be posed independently.

“When [Joy] first showed me the rig, I said: ‘Okay, that’s intimidating’,” recalls Hudson. “But then the animators got it, and suddenly Dan came to life. You had a little dandelion that was thinking and emoting.”

For the pivotal shot in which Dan pulls his roots out of the ground, animator Wayne Unten created a 2D preview of the movement, later going back to match the poses in 3D frame by frame.

Character animation

One of those animators was Johnson’s collaborator on Elsa – and fellow VES Award winner – Wayne Unten, who choreographed the crucial shot where Dan pulls his roots out of the ground.

Not wanting to get bogged down in mastering the complexities of the rig – which he describes as being like “six ropes tied together” – Unten elected to animate the shot traditionally, then match the results frame by frame in 3D. The result is an elegant balletic move that recalls the furling of a flag as much as it does conventional character animation.

“When Wayne showed me the [2D] animation, my reaction was: ‘Oh my god, the rig isn’t meant to do that,’ recalls Hudson. “He just said: ‘Don’t worry. I’ll make it work.’

And work Unten did, creating a one-off solution employing clusters and nonlinear bend deformers, wrap deformers and a blendshape back into the main geometry to coax Dan into the appropriate shapes. The shot was the last to be completed, with the team locking the edit using Unten’s 2D preview rather than the final 3D animation – the other, less complex, shots using the default rig having been completed long before.

Effects elements in Weeds include the jets from the sprinklers, water splashes and puffs of steam. The heat distortion effect uses the same setup that Disney created for use on its feature film Moana.

Effects animation

Weeds also features a deceptive number of effects animations: most obviously, the sprinklers on the lawn in Spielbergland, but also interactions between the water droplets and the ground, puffs of steam when Dan’s roots touch the hot concrete, and heat distortion. This was created using the same setup that Disney used on Moana, with the volumetric effect being rendered out to create a distortion map for use in compositing.

“We benefited from the fact that the pipeline was already set up for us,” says effects animator Hendrik Panz, who worked on a number of the key shots, and ended up serving as overall VFX advisor for the project. “It was easy for us to get the effects from Houdini to Maya for rendering.”

Panz was also instrumental in convincing Hudson to use an actual hair system for the sparse down on Dan’s stem, rather than faking the effect with transparency-mapped cards: something that greatly improved the way in which the hairs respond to the lighting in the scene.

“As an artist, it’s very easy to become stuck in your little bubble and convince yourself that what you’re doing is good,” says Hudson. “Sometimes it’s good to have someone come into the bubble – particularly if that someone is a six-foot-four, two-hundred-pound German – and say, ‘That looks crap. Do it again.’”

Lighting and rendering

Hudson handled most of the lighting on the short himself. The set uses 14 lights in total, including separate sun lights to illuminate Dan’s face and body – ensuring that his face catches the light without changing the angle of the shadows in a shot – and multiple Quad Lights to shade and paint the scene. The latter generate the rim lighting effects and mimic the effect of light bouncing off the concrete driveway onto surrounding surfaces. There’s even a back light linked to the water, to give it a magical glow.

Weeds was rendered on Disney’s in-house farm, mainly over weekends. “I’d get up early Saturday morning and most of the jobs that people had put in the queue on Friday would be done, so I could kick off my own renders” recalls Hudson. “By Sunday morning, I could see how everything looked and work on anything that needed re-rendering. By Monday before work, I’d be able to comp a new version and be done with it.”

The final touch was the score, created by the only non-Disney employee to work on the project: composer Dale Turner. To satisfy Hudson’s desire for “organic, acoustic” sounds, Turner tried a conventional guitar before settling on its smaller cousin, the charango, one of which he had just been sent from Bolivia. “When it arrived, I thought, ‘Well, this has emigrated to the US [too]’,” says Turner. “It was like its own little immigrant.”

Watch the film online

Weeds has already qualified for next year’s Oscars, and is currently doing the rounds of the festival circuit – although you can take advantage of a break in screenings to watch the film online until the end of the month.

Hudson attributes the quality of the finished short to the collaborative working culture encouraged at Disney, in which any artist can offer their feedback on any part of a project.

“I don’t think any film should be an individual effort,” he says. “People at Disney understand the language of film; they understand what makes a good movie. I saw the film elevate with every person who came on and contributed their ideas to it.”

The afterlife of Weeds

As the first project to have been be completed entirely within the studio’s independent film-making program, Hudson hopes that Weeds will inspire other Disney artists to create their own shorts. “Since we finished, about six other people have talked to me about doing a short, and have now filed the paperwork,” he says. “That’s super-inspiring to me. I’ve proved that it can be done: now other people can do it bigger and better.”

Hudson also hopes to donate Weeds to an organisation that can use it to bring awareness to the challenges facing the human immigrants that inspired the project. “Shorts have a brief lifespan,” he points out. “But to give it to someone that could use it in a way to help other people would be a fantastic end to the film.”

“Animation is a powerful medium for creating empathy,” he concludes. “If we make people feel differently, we can make them think differently. And if we can make them think differently, we can change the world.”

Watch Kevin Hudson discuss the making of Weeds in a talk at Gnomon earlier this month