fmx 2011: Thursday’s news

In the third of our reports from Europe’s premier CG festival, Jim Thacker delves into stereoscopic workflow to be told why stereo pre-viz isn’t worth doing – and why this year’s stereo-converted blockbusters may be in trouble.

Thursday was stereoscopic production day at fmx, with sessions covering everything from aesthetics to the King Kong 360 3-D theme park ride.

Thursday was stereoscopic production day at fmx, with sessions covering everything from aesthetics to the King Kong 360 3-D theme park ride.

But away from the giant apes, some of the most interesting – and most sobering – information for working artists came in the afternoon, in the shape of the sessions on 3D workflow.

Ron Frankel from Los Angeles pre-viz studio Proof was up first to discuss the problems of stereosopic pre-viz, drawing upon his experiences on movies such as The Amazing Spider-Man and Underworld 4.

“It takes more time and money to create stereo pre-viz,” Frankel pointed out. “So we have to ask: are the film-makers getting enough out of it on a creative, financial and technical level to justify that extra expense? And my short answer is: not really.”

The issue, Frankel believes has less to do with stereoscopic effects themselves than the tools currently available to analyse them – and crucially, to display them on set.

“Feature film pre-production is incredibly hectic,” Frankel said. “Everyone is making tons of decisions every day, trying to get ready for that first day of shooting. With mono pre-viz, we can [deliver] everything as QuickTimes: we can upload it to the network, email it to people, they can look at it on their iPhone. It’s available anytime, anywhere. With stereo pre-viz [we have to get everyone round a screen].”

Throw in the complexities of multiple stereo display formats – and even of ensuring that there are enough stereo glasses to go round – and stereoscopic pre-viz can simply delay pre-production too much to be useful.

“If that time delay [is] more than a few hours, people have moved on from that decision,” said Frankel. “There’s no point in looking at [the pre-viz]. And if there’s no point in looking at it, there’s no point in making it.”

However, Frankel pointed out, stereo pre-viz does have its place in less time-critical situations: as a sandbox for directors and cinematographers new to stereoscopy, and simply for its ‘wow factor’.

“When the studio execs see it, everyone gets excited. It’s a great way to build enthusiasm in the project, to build confidence in the project.”

The challenge for Proof, and other studios like it, is to develop ways of working that can allow stereo pre-viz to escape from those ghetto areas. Just 29% of the pre-viz for The Amazing Spider-Man was done in stereo: a figure Frankel believes is typical across the industry.

New on-set display tools

Proof is currently developing new tools that will enable it not just to visualise the effects of adjustments to the stereo camera rig, but to communicate them to those on set who may be viewing the results in mono – or even as paper print-outs.

Its first attempts range from a simple top view inset into the pre-viz showing the camera frustum and convergence plane to a more complex split-screen view with proper analytic tools (pictured below).

Proof’s tools for demonstrating stereo effects on set without a stereo monitor. Upper left: actual pre-viz. Upper right: top view showing camera frustum and convergence plane. Bottom right: colour map showing where objects violate stereo safe zones. Bottom left: view through stereo image processor. The studio operates a Maya-After Effects-Premiere pipeline.

But the problems with pre-viz aren’t the only issue with stereoscopic movie-making. As Grant Anderson from Sony Pictures Imageworks pointed out, the industry faces a shortage of high-quality stereo conversion facilities.

“I think this year is going to be very interesting,” he said. “All of these movies that have been announced as going to 3D [which include Men in Black 3 and The Green Lantern] are trying to line up conversion vendors ? but there aren’t going to be enough vendors. So you’re going to see some movies that were announced that aren’t going to come out in 3D.”

Sony is currently working to educate the industry in stereo techniques (a not entirely disinterested move, given its huge investment in stereoscopic Blu-ray and other media) through its new 3D Technology Center.

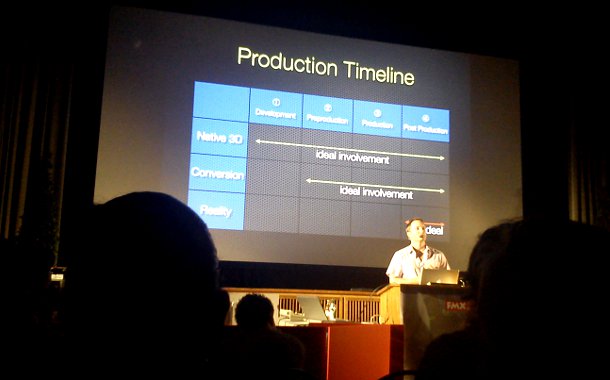

Ideal and actual stereo production timelines. As SPI's Grant Anderson points out, reality is often far from ideal.

Over 1,200 cinematographers have taken the Center’s free three-day training course in its first year alone. Sony is now widening out the course to directors and VFX artists, and will also be training in London this summer.

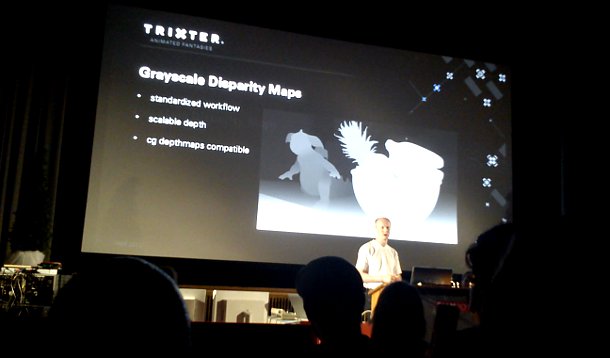

One of the facilities already up and running with stereo conversion work is Germany’s Trixter, which worked on dimensionalising The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Green Hornet.

The studio’s stereoscopic supervisor, Dietrich Hasse, discussed some of the methods Trixter has developed to automate the conversion process without sacrificing creative control, which include the use of greyscale disparity maps and a custom plug-in to view the results as point clouds within Nuke.

Hasse commented on the need for the conversion process to be planned properly from the start of production, if the medium is to evolve from its early, eye-bleeding days.

“Personally, I hope the conversion of complete movies will only be a temporary phenomenon,” he said. “Last year, there wasn’t any [alternative], but movies that [are starting production] now and which are planned in 3D are a whole different matter.

As Hasse pointed out, simple things like a proper ‘depth briefing’ and making assets such as alpha mattes, depth passes and background plates available to conversion facilities can mean the difference between a rushed, shoddy-looking job and proper, creatively driven dimensionalisation.

But love or loathe the results, all of the speakers felt that the stereo-converted movie is here to stay. Even on projects that are filmed entirely in stereo, dimensionalisation will still be necessary to rescue failed shots or to achieve effects that would be impossible in the real world.

Or, as Hasse put it: “As long as there are stereo movies, there will always be conversion.”

View more highlights from fmx 2011 on the show website (includes live webstreams of some sessions)