fmx 2011: Wednesday news

In the second of our reports from Europe’s premier CG festival, Jim Thacker trawls through the murky world of industry politics and discovers why leading VFX studios are increasingly getting into open-source software.

Their enthusiasm undiminished by the first night’s festivities, the crowds at fmx 2011 seemed, if anything, even thicker on the second day.

With most of the audience in the Gewerkschaftshaus screening theaters sitting tight between sessions, it was often difficult to get in to see headline events such as ILM’s session on Rango, or the festival’s Focus on France strand, which showcased a wide range of work, including Chez Eddy’s titles for Splice.

Paris studio Chez Eddy presented a making of session on its work on genetic engineering fable Splice.

However, we did catch Visual Effects Society chair Jeff Okun’s zingy presentation on politics in the VFX industry.

“There are two kinds of politics,” Okun commented. “Reasonable politics, where you work through the system to get what you want, and Crazy People politics. [Since we work with artists], 95% of the politics in our field is Crazy People politics.”

In evidence, Okun went on to rummage through some of Hollywood’s murkier corners, drawing on his own experiences on such notoriously troubled productions as Cutthroat Island, Red Planet – and, more recently, the rushed stereoscopic conversion of Clash of the Titans.

To do justice to Okun’s anecdotes would require an article in its own right (and a really good libel lawyer), but his tales of the turf wars between directors, producers, actors and art crew – usually with the visual effects staff caught in the fallout – confirm most of the popular prejudices about how Hollywood works.

“Everybody has their own agenda,” he commented. “You would think those agendas are to do with making the best possible project, but uglily enough, that rarely enters the equation.”

Ultimately, despite making for a thoroughly enjoyable hour, Okun offered no advice on how to survive the system.

“The reward for being good at politics is the same as being bad at politics,” he commented. “You don’t get [rehired] for making life smooth for everybody: what’s up on screen is all that matters.”

The future will be open-sourced

Meanwhile, back in the main venue, the technical presentations were in full swing. We heard good things about the sessions on interface design – in particular, the two-hour talk from pioneering researcher Ken Perlin.

However, the main draw for the afternoon was the conference on open-source production tools, which featured senior staff from Disney, Pixar, Sony Pictures Imageworks, Weta and Double Negative, and examined the reasons for the recent explosion in in-house technologies being released to the world at large.

The year zero in the field was 2003, with ILM’s open-sourcing of the OpenEXR file format: since universally adopted as an industry standard for high dynamic range images.

“I can be sent an OpenEXR file, drag it to my desktop, hit the Spacebar, and my Mac can show me it. That’s how successful it is,” commented Imageworks CTO Rob Bredow.

Imageworks CTO Rob Bredow identifies ILM's open-sourcing of the OpenEXR file format as a critical moment in the industry.

ILM’s work prompted Bredow to set up Imageworks’ own open-source programme, which has resulted in such high-profile projects as the Open Shading Language and the Alembic data-transfer format: an attempt to create an open alternative to de facto proprietary standards such as OBJ.

The initiative prompted Disney to follow suit with the Ptex UV-less texture format. Pixar is currently trying to do the same thing with soft-crease (Catmull-Clark) subdivison surfaces, while Weta has also taken its first steps into open-sourcing.

For studios, one benefit of open standards is not having to reinvent the wheel. “After I left my last company, I was walking away from years of work and it killed me to be back at the starting point,” commented Imageworks’ principal software engineer Larry Gritz about his decision to set up the OpenImageIO API, now used at Imageworks, Digital Domain and Double Negative, and in the commercial tools Arnold and Mari.

“I’d done [this work] four times and I wanted to [make it open source] so I didn’t have to blow my brains out.”

Another is the sharing of development costs: “If you have a file format, it can be valuable to spread it [to other developers] so all your tools work the same way,” commented Gritz. “If you keep it proprietary, you could be stuck writing plug-ins forever.”

Gritz also believes that open-source development results in better code – primarily because programmers are motivated by the thought of having their work held up to public scrutiny. “We’ve made some whopper mistakes [and] the dirty laundry is all out there for people to see,” he said.

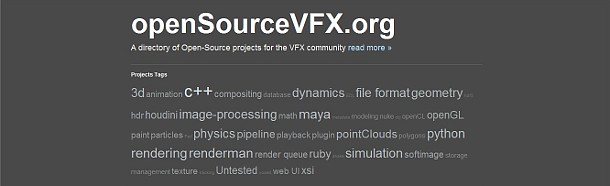

But not all open-source projects are equally successful: a fact that recently led Gritz and Bredow, together with Philippe Leprince, Double Negative’s head of lighting and rendering to set up OpenSourceVFX.org: a directory of the most useful tools.

The site currently lists 54 projects felt to address genuine industry needs, and on which development is proceeding actively.

“[On standard open-source sites] it’s a bit of a needle in a haystack finding something that will work for you,” commented Leprince. “There are a lot of ‘zombie projects’ out there.”

The end of commercial tools?

So does the rise of open-source technologies threaten commercial applications like 3ds Max or Maya? Probably not, according to the panel.

Several speakers commented on the need to withhold technologies that still give a studio a commercial edge over its rivals (to “triage the things you need to keep proprietary,” as Gritz put it); and it was universally felt that file formats like OpenEXR and Ptex are easier to open-source that entire applications, or even GUIs.

The issue is legal as well as technical. Speaking about Apple’s decision to discontinue Shake, Dan Candela – now director of studio technology at Walt Disney Animation, but then working for the developer – commented that a fear of patent infringement lawsuits dissuaded Apple from releasing the software open source.

“If you open-source a huge application like that, you’re creating a target where people come out of the woodwork to say, ‘I did that’,” he said.

A series of hurdles: Weta CTO Sebastian Sylwan considers the proplems of production software development.

Legal hurdles also crop up in the form of the numerous different licence agreements under which open-source software may be released.

“From a commercial point of view, [the popular GPL licence] is really hard. [Its conditions] make it difficult for commercial vendors to contribute [to open-source projects] and that’s a shame,” said Phil Parsonage, lead engineer for The Foundry.

“We’ll never integrate our own code [into GPL projects], because it’s just too risky,” agreed Weta Digital CTO Sebastian Sylwan. “There will always be some developer in some department somewhere who won’t consider the fact that the code is GPL and will link against it.”

Sylwan, like the rest of the panel, considered that the shorter, simpler Modified BSD licence was the only viable basis on which more complex open-source production tools could be released.

The future is bright: the future is open source

Ultimately, however, the panel were optimistic about the future of open-source production tools. While it will take some years for studios to lose the mindset that all proprietary technology must be protected jealously, as Gritz pointed out: “VFX studio versus VFX studio is only one way to look at it. The other way is vendors versus the people hiring us.”

Ultimately, he felt, the aim is to create a “climate of trust” in which the mutual rewards outweigh the cost to any individual studio. The power to create that climate lies in facilities’ own hands: it only remains to be seen whether they can surmount the remaining legal and logistical hurdles.

Or, as Phil Parsonage put it: “[The future] will be awesome – as long as we don’t screw it up.”

View more highlights from fmx 2011 on the show website (includes live webstreams of some sessions)