FMX 2012: Where next for virtual production?

In this feature, we round up our coverage of the show’s Virtual Production Track, and assess what impact these creative but disruptive technologies may have on the way we make movies, videogames and TV shows.

It takes a certain kind of confidence to devote an entire three-day conference to something that no one can actually define. Yet that’s precisely what the organisers of the FMX festival just did.

The Autodesk co-curated Virtual Production Track at FMX 2012 spanned 16 separate presentations, panel discussions and workshops, covering virtual production for features, episodic TV and videogames.

Speakers included staff at some of the industry’s leading studios, including Weta Digital, ILM and Digital Domain, not to mention VFX legends Rob Legato and Douglas Trumbull.

Yet, as speaker after speaker pointed out, no one seems quite sure what virtual production actually is.

![]()

James Cameron on the set of Avatar: the “birthplace of pure virtual production”, according to FMX keynote speaker John Kilkenny. But virtual production is much bigger than the technology Cameron developed.

The broad and narrow definitions

At first, the answer seems obvious: virtual production is Avatar – or at least, the style of film-making James Cameron pioneered on it: something you can read about in more detail in this archive feature.

John Kilkenny, Executive Vice President at 20th Century Fox, even namechecked the movie in his keynote, calling Avatar ?the birthplace of pure virtual production?, and describing his ?lightbulb moment? of seeing the director pacing around an empty stage, only to discover he was scouting locations on the planet Pandora.

Yet as former Manex Visual Effects president David Morin, who chaired the sessions, pointed out, this is only one of two possible definitions of the term. Under the ‘narrow’ definition, virtual production simply entails providing a director with real-time CG feedback live on stage.

Virtual production at ILM

This technological view of virtual production was explored by Industrial Light & Magic in its presentation on its own in-house workflow. Introducing the session, Steve Sullivan – Senior Technology Officer at ILM parent company Lucasfilm – identified six key components of a virtual production workflow:

- Previz

- Rapid prototyping of project assets

- Pitchviz

- Performance capture

- Final camera

- Virtual worlds

As Sullivan pointed out, the first of these was largely pioneered at ILM.

Studio founder George Lucas had been experimenting with blocking out movies using edited archive footage or puppet animation since the late 1970s; while the birthplace of modern digital previz is commonly held to be the Skywalker Ranch, where the future founders of The Third Floor, Halon Entertainment and 20th Century Fox’s Cinedev in-house previz team all worked on Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith.

?Previz has been a passion of George’s since the late 1970s,? said Sullivan. ?He wanted a tool [simple enough that] directors could sit on their sofa watching CSI and mark up shots for the next day.?

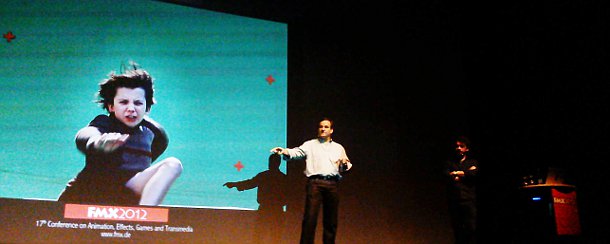

Part of the virtual production process: assembled hacks test ILM’s final camera system on the studio’s in-house mocap stage during an Autodesk press visit earlier this year.

While ILM’s in-house previz tools, the game-engine-inspired Zviz and Gwiz, aren’t usually used in isolation (?The director will still head off to the 3D story team to plus [the result] up a bit,” commented Sullivan), they are designed to be simple enough for people without a background in 3D to use.

Proprietary technology also plays its part in the remaining parts of the virtual production pipeline, in the shape of ILM’s autorigging systems and motion library, used to rapidly prototype character assets for projects; its celebrated iMocap on-set performance capture system; and its final camera system, which enables directors to visualise camera moves around a virtual environment from the studio’s mocap stage.

(The ‘camera’ itself consists of a modified Wacom tablet with tracking markers attached, we were intriguted to discover on a visit to the studio earlier this year.)

For the studio, these technologies form a kit of parts, any or all of which can be deployed according to the needs of a project. As digital supervisor Michael Sanders pointed out, since ILM is a service facility rather than a film production company in its own right, it has to remain agnostic about the way in which directors wish to work.

?This is less of a philosophy for us, and more of a technology mandate,? he said. ?We’re not overselling these things. We don’t say: ‘You have to do this in real time.’ It’s only if it aids the creative process.?

Ahead of the game: producer Peter Jackson and director Steven Spielberg on set on The Adventures of Tintin. Animation house Weta Digital takes a broader view of virtual production than many studios.

The broader view

A contrasting view of virtual production – in David Morin’s terms, the ‘wide’ definition – was set out by Weta Digital in its session on The Adventures of Tintin. Although still a facility for hire, Weta has had the experience of working ‘end to end’ on some of the largest virtual productions to date, from Avatar to The Hobbit.

This experience may have shaped its view of virtual production as something more than a set of tools – as Weta CTO Sebastian Sylwan put it, ?There’s no checklist of [technologies] you can go through and say: ‘If you have all of these, this is virtual production.’?.

Instead, Weta outlined its vision of virtual production as a broader cultural shift in the film-making process, one that will erode the boundaries between previz and final effects, enable visual artists to contribute to story development, and ensure key creative decisions can be taken at the very beginning of production.

Read a fuller discussion of Weta’s ideas, including its three key goals for virtual production

Making 300 in real time

It’s one thing to talk generally about virtual production empowering artists creatively, or enabling them to contribute to the storytelling process. But what really captures the attention are concrete predictions.

Zoic Studios co-founder Loni Peristere had predictions aplenty – the most headline-grabbing of which was that if we were to remake 300 now, we could do so in real time.

The claim came during Peristere’s presentation on Zoic’s proprietary ZEUS ‘environment unification system’, which enables the studio to integrate greenscreen footage with prebuilt 3D assets live on set, and feed the results automatically back into its Shotgun asset-management software. A new Unity-based iPad app makes it possible for directors to make their own camera and lighting changes.

The system currently enables Zoic to generate up to two million frames of final-quality effects – that’s almost 24 hours of VFX – a month during the course of its work in episodic TV.

Peristere went on to speculate what would happen if the same technology were applied to films, predicting not only that movies that would once have cost $120 million could now be remade for $30 million, but that it would soften even Inception director Christopher Nolan’s notoriously sceptical view of digital technology.

As he put it: ?That’s super-exciting for Chris Nolan. It’s super-exciting for fans of cinema. And it’s super-exciting for me, because we’re going to change the world with this.?

Read a transcript of Loni Peristere’s entire presentation

VFX supervisor Rob Legato (left, with Pixomondo’s Ben Grossmann) explores the Oscar-winning effects of Hugo.

A cautionary tale

But the consequences of this new way of working aren’t all positive. As speaker after speaker pointed out, the problem with making creative decisions earlier in production is that directors will hold you to them.

Nowhere was this better illustrated than in the session on Hugo’s Academy Award-winning visual effects, in which VFX Supervisor Rob Legato revealed how a seemingly throwaway decision made during the first week of previz came back to haunt both him and the effects team at Pixomondo.

We ran a longer story on this session, so we won’t spoil the surprise for you here. But if you’ve seen the movie, consider this: what do you remember about its opening shot? We’ll lay even money that the part that nearly drove its effects crew to despair was the one thing you never even noticed.

Read about the Hugo shot that almost killed Rob Legato

Come back next year for the answer

But after all of that, are we any closer to defining what virtual production actually means? Well, not exactly. Over the course of the three days, there were almost as many views advanced as there were speakers, from the extremes of David Morin’s ‘wide’ and ‘narrow’ definitions through all points in between.

Perhaps Weta’s Sebastian Sylwan put it best when he reflected that the real definition of virtual production will not be what we think we can do now, but how we – not just artists and technologists, but writers, directors and producers – change the way in which we collaborate in years to come.

?If it’s hard to come up with a definition that serves all the possible aspects of virtual production, I think this is because it’s a process of learning and exploration: a process we are all involved with,? he said.

Bad news, perhaps, for journalists looking for neat endings for their articles, but good news for FMX itself: the show has announced that the Virtual Production Track will now form a regular part of the festival, returning for another round of sessions on 23-26 April 2013.

View recordings of key sessions from the Virtual Production Track on Autodesk’s AREA website

(Includes presentations not covered above.)