Expert advice: weapon designer Paul Ozzimo

The creator of the Star Trek’s Phasers and Men in Black’s De-Atomizer tells us about rapid sketching, thinking physically and the ‘golden ratio’ of classic gun design, as set out in his upcoming Gnomon Master Class.

Paul Ozzimo’s resume reads like a history of effects movies. Starting out as a physical model maker in the late 1980s, he worked on many of the landmark films of the period, including The Abyss, Batman Forever, Starship Troopers and Armageddon, before switching to 3D modelling on Sam Raimi’s 2002 Spider-Man.

Paul Ozzimo’s resume reads like a history of effects movies. Starting out as a physical model maker in the late 1980s, he worked on many of the landmark films of the period, including The Abyss, Batman Forever, Starship Troopers and Armageddon, before switching to 3D modelling on Sam Raimi’s 2002 Spider-Man.

A versatile vehicle, prop and costume designer, he has worked on most of the key VFX franchises of the past decade, including Superman, Mission: Impossible, Transformers and Star Trek. Some of his most iconic work has been weapon design, including Star Trek’s Phasers, and Men in Black’s classic De-Atomizer.

In Weapon Design for Film, his session for Gnomon Master Classes 2014, held online from 23 June to 6 July, Paul will be demonstrating some of the techniques he has developed over the course of his varied career. We caught up with him to discuss the workshop, and find out more about the value of rapid sketching, thinking physically – and the ‘golden ratio’ of gun design.

CG Channel: Weapon design seems a pretty specialist topic. Why devote an entire class to guns?

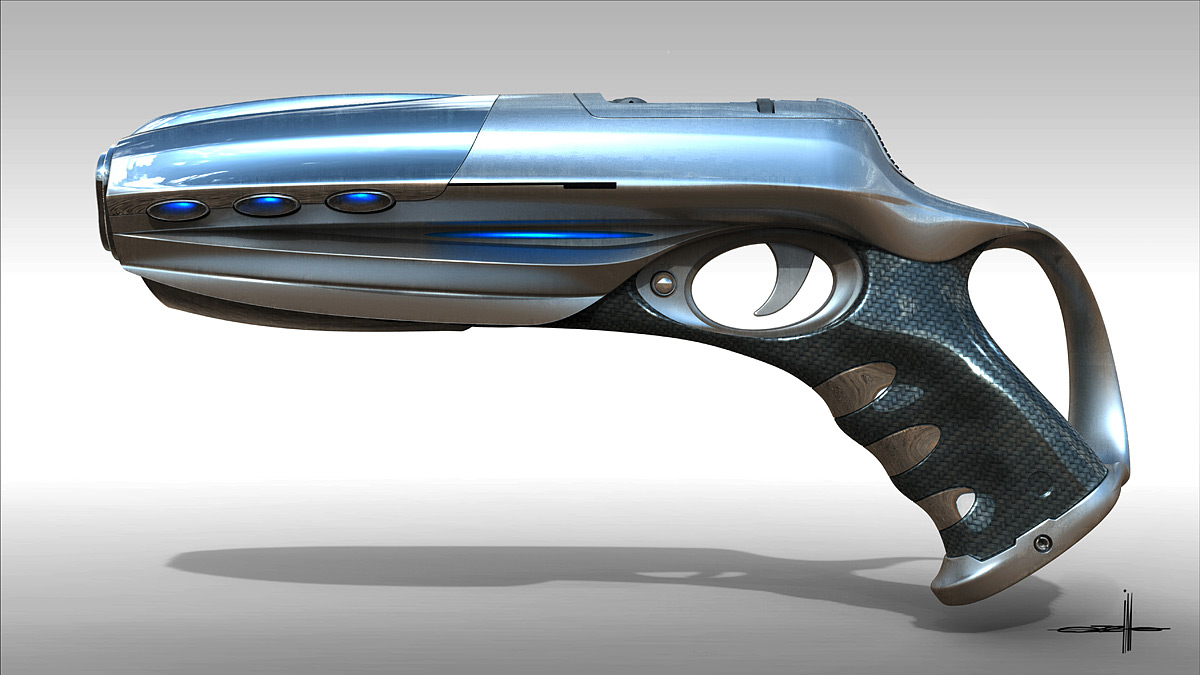

Paul Ozzimo: In production, I do a lot with vehicles, and some costumes – I consider myself a chameleon: I can change over to whatever the designer needs me to do – but I wanted to do something fun and quick. I’ve done guns for many films, and they’re a chance to come up with great geometries and different materials.

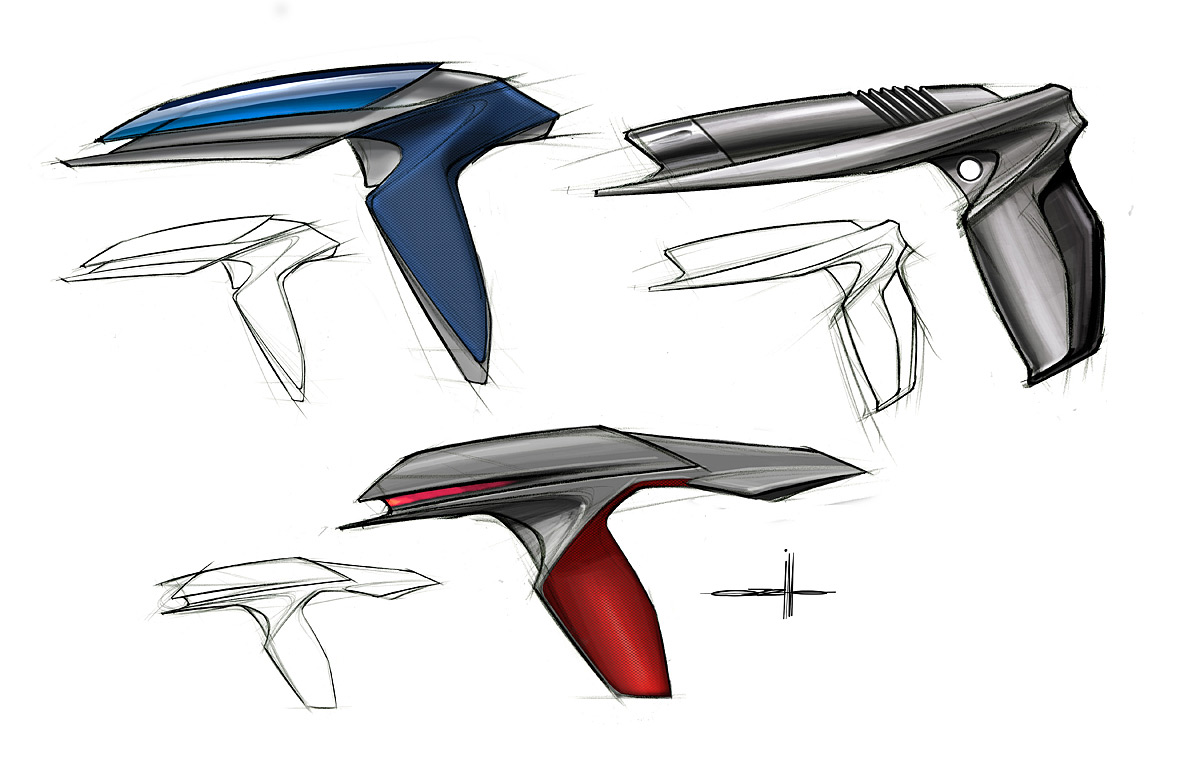

Quick sketches are a great way to begin your design work, says Paul. It’s important to be able to generate a lot of variant ideas quickly so that a director can pick their favourite before starting to refine the concept.

CGC: What are you going to be covering in the class?

PO: I’ll start with silhouette sketches – maybe three or four, just to show the design process – pick one of them, start to fill it in a little more, and time permitting, I’ll do a little bit of 3D to give a stronger basis to sketch over.

CGC: Is that typical of your own production workflow?

PO: Yes, it’s very important to do as many quick sketches as you can so the director can decide which one they prefer. It’s easy to get approvals if you do.

Paul has been using 3D in his production design workflow since 2002’s Spider-Man, having first begun to experiment with the technology with version 1.0 of Rhino – then available to download for free online.

CGC: Do you typically model in 3D in production?

PO: I was a model-maker back in the 90s on [movies like] The Abyss, so I started with analogue models. Back then, I could see computers starting to come into our industry in a big way. One of the first programs I got involved with was version 1.0 of Rhino. I was in San Francisco, working on Bicentennial Man, and I was trapped in my hotel room – it was pouring with rain outside – and I downloaded it and started to play around with it.

The first job I used it on was the Spider-Man – the first one, with Tobey Maguire – where I got a chance to do The Green Goblin’s glider in Rhino. Nobody at the time had seen anything like that in an art department. There were no computers, even: it was all paper and bits of plastic and clay – in fact, they’d called me in to do the glider in clay. My two-week job became three months. It was also one of the first movies that used rapid prototyping.

CGC: Do the designs you produce have to be fabricated? What constraints does that impose?

PO: Yes, most of the time I’m called in for things that will be constructed. With Rhino, the constraint is really just the shape of a person. If I’m doing a prop – a helmet especially – I need a hard dimension for the person who’s going to be [wearing it]. Once those hard dimensions are set, I bring [the geometry] into a poly modeller – I prefer Softimage – and slam out shapes around my original framework, and it all stays to scale.

CGC: Are there any rules for weapon design?

PO: If you take your hand and point it like you’re a child playing Cowboys and Indians with your finger sticking out, your three fingers curled and your thumb sticking up, that’s what I call the ‘golden ratio’. Unless you’re designing for an alien hand, the ratio of your finger to your thumb to your trigger fingers folded around the base of the grip has to be the the same, or the gun just isn’t comfortable for the actor on set.

The key constraint the need to fabricate props physically imposes on concept designers is human scale. Fail to take account of the proportions of a human body, and designs become impossible to use on set.

CGC: Do you ever still make physical models?

PO: Just the other day I went back to my storage unit and pulled out all my old Star Wars model kits and introduced my five-year-old son to them. We built an X-wing together. He’s probably the only kid who’s built a model kit in the last ten years.

It brought back everything I miss about modelling, which is the smell: the smell of the plastic and the glue, and the water decal paper. I think what I miss most about making models for movies like Starship Troopers is the paint.

CGC: Did physical model-making teach you anything you couldn’t have learned digitally?

PO: I think the biggest benefit is that you have a better grasp of how things assemble. It’s easy to fool everybody in CG, because nothing needs to support itself, or have thickness. But it adds an element of believability when you say, ‘Okay, if this mass really were hanging here, it would have to be supported better.’

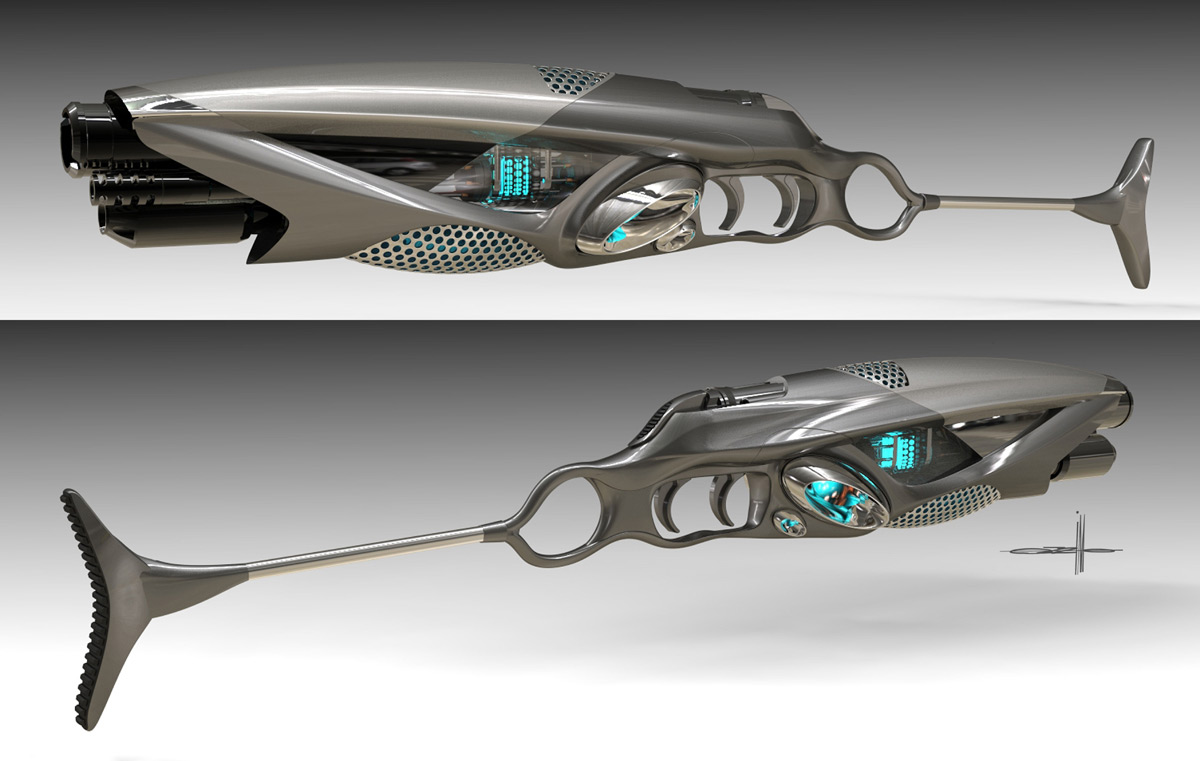

Two takes on Men in Black’s De-Atomizer: the ‘Series 1’ 1960s model (top) and the Standard version (above). Paul based the design on old camera flashbulbs, suggesting how the weapon would function in real life.

CGC: Do you have a favourite gun design from the movies you’ve worked on?

PO: I was thrilled to do the Phaser for the last Star Trek films. I was honored by the chance to do it, and it was a lot of fun, working with JJ Abrams.

But I think my all-time favourites were the guns for Men In Black, because they spanned an era. We had to go back and do research on guns of the time. The ‘Series 1’ De-Atomizer – the one the young Tommy Lee Jones had – was the best because I based it on tube technology. It’s basically a series of flashbulbs from old cameras. It’s a series of three glass cylinders in a row. The idea behind it was that each time he fired it, it would fry out and fill with kind of silvery material [like a burned-out flashbulb], and he would crack it out and replace it.

In design, you have to be able to show the process. I had to show how the gun worked, the technology behind it, and how he would change it out. If you take a little time out [to think about these things] for every design you do, it almost designs itself.

An illustration of The Fallen from Transformers: Revenge of The Fallen. Paul describes himself as a chameleon: able to switch between different types of design work to suit the needs of a production.

CGC: What’s your top tip for would-be concept illustrators?

PO: Speed. Learn to draw, but be quick. A lot of times, when a director or production designer asks to see some ideas, they want to see 20 ideas by the end of the day. And if that means sketching the old fashioned way on paper with a pencil, then great. Or working in black and white; doing silhouettes.

These days, I see a lot of people getting bogged down in 3D. I’m not knocking 3D, but there’s a time and a place for it, and that’s after a lot of thought has been put into the concept. In movies, you have a limited time schedule, and the director wants to choose quickly. Only then do you get into the 3D and the materials – the fun stuff.

CGC: What about personal qualities?

PO: A good attitude. I’m not necessarily the best artist out there. Off the top of my head, I can tell you 10 artists who are much better than me. But in the art department, having a great attitude makes a big difference.

If you’re handed the lead character to design, do it proudly – but if you’re designing door knobs, do it with the same enthusiasm. Because [if you don’t] it will get back to the people higher up, and they’ll see that you’re the guy who insists on doing lead characters.

Some people consider things like doors or door knobs small jobs, but you just never know what the director will focus attention on. Maybe he’ll love that door you put a lot of attention into and feature it in a shot. Everything is big. Everything can be seen. Always design as if your work is going to be seen in close-up.

Sign up for Gnomon Master Classes 2014 ($265 for all 14 sessions if you register before 6 June)

Full disclosure: CG Channel is owned by the Gnomon School of Visual Effects.